Toddler (1–3 Years): Positive Parenting Tips

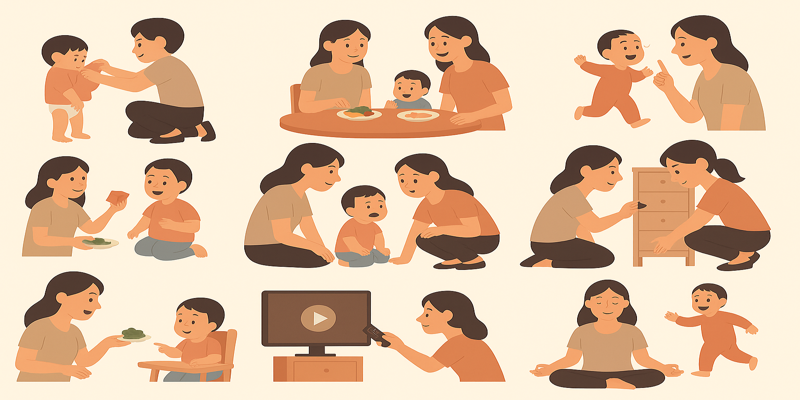

The toddler years (ages 1 to 3 years) are a phase of rapid development and exploration—marked by strides in language, motor skills, social-emotional growth, and burgeoning independence (Verywell Family, 2017; Raising Children, 2024a). Navigating this energetic period can be rewarding—and challenging. Here are evidence-based positive parenting tips to support toddlers constructively. 1.0 Encourage Independence through Everyday Tasks A sense of autonomy empowers toddlers and fosters self-confidence. Simple chores—such as helping to dust, wash their hands, feed themselves, or undress—promote independence and purpose (Raising Children, 2024b; Michigan.gov, n.d.). Allow toddlers to participate in meals by stirring ingredients or setting the table, cultivating both practical skills and a sense of contribution (HealthyChildren.org, n.d.). 2.0 Create Predictable Routines and Quality Time Consistent routines help toddlers feel secure and aid regulation. Regular family meals—ideally daily, or at least several times a week—provide chances for connection and modelling behaviours (HealthyChildren.org, n.d.). Scheduling short, uninterrupted special time, like 10–15 minutes of play or reading, strengthens emotional bonds (Parents.com, 2015). 3.0 Use Positive Language and Redirection Avoid power struggles by framing behavioural guidance positively. For instance, say “Please walk” instead of “Don’t run,” shifting attention to desired actions (Happiest Baby, n.d.). This communicates expectations clearly while preserving the toddler’s dignity and sense of respect. 4.0 Foster Language and Cognitive Development Through Play Everyday moments are rich with opportunities for learning. Simple games—like naming body parts, matching shapes, or asking toddlers to find objects—promote language skills and cognition (CDC, 2025a). Engaging in interactive mealtimes, bedtime reading, counting games, or outdoor play stimulates brain development, social skills, and confidence through natural, enjoyable activities (The Sun, 2023). 5.0 Set Realistic Expectations and Use Positive Discipline Understanding that toddlers are learning and refining their abilities promotes empathy. Discipline should focus on teaching, not punishment (Parents.com, 2015). The Positive Discipline model emphasises mutual respect, long-term effectiveness, and teaching life skills rather than coercion (Wikipedia, 2025a). For example, involving toddlers in creating fair rules helps them feel responsible and invested (Wikipedia, 2025a). 6.0 Reflect on Emotions and Behaviour Reflective parenting—the ability to imagine your child’s mental and emotional states—deepens connection and aids emotional development (Wikipedia, 2021). Recognising what a toddler may be feeling beneath their actions allows responses in a kind and developmentally supportive way, enhancing trust and self-regulation. 7.0 Ensure a Safe Environment Toddlers are curious climbers, so home safety is paramount—secure heavy furniture to walls, prevent access to unstable items, and use stair gates or window guards (Wikipedia, 2025b). Meal safety and supervision help reduce choking risks; toys should be checked regularly for hazards, especially for ages 2–3 (CDC, 2025b). 8.0 Support Nutrition and Healthy Growth Toddlers require nutrient-rich diets to support rapid growth. Introduce a variety of textures and flavours while ensuring essential nutrients like iron, calcium, and vitamin D (Wikipedia, 2025c). Allow toddlers to self-feed to encourage independence, but screen foods carefully for choking risks (Wikipedia, 2025c). 9.0 Limit Screen Time and Encourage Play Excessive screen use may impact behaviour and attention. One parent reported calmer, more affectionate behaviour after eliminating screens, with longer periods of imaginative play and fewer tantrums (The Sun, 2025a). Experts suggest limiting toddler screen time to short durations—around 15 minutes per session and up to one hour per day (The Sun, 2025a). 10.0 Practice Mindful Parenting and Balanced Flexibility Life with toddlers can be hectic—mindful parenting strategies like pausing, responding with compassion, and creating tech-free moments help maintain calm and connection during chaos (Times of India, 2025a). Embracing flexibility—preparedness with room for spontaneity—can reduce stress and enhance family enjoyment (Parents.com, 2025). 11.0 Summary of Key Positive Parenting Strategies for Toddlers Tip Goal / Benefit Encourage independence Builds confidence, skills, and autonomy Establish routines & quality time Enhances security, bonding, and regulation Use positive language Encourages cooperation and respect Promote play-based learning Supports language, cognition, and joy Set realistic expectations Fosters teaching, not punishment Reflect on emotions Builds emotional understanding and regulation Ensure safety Prevents injury and creates safe exploration Support nutrition Fuels healthy development and independence Limit screen time Encourages focus, creativity, and connection Practise mindfulness and flexibility Reduces stress and strengthens family cohesion Parenting toddlers is a dynamic journey filled with high energy, boundless curiosity, and emerging independence. By using positive, respectful, and consistent strategies you empower your child to learn, regulate, and grow within a loving environment. From offering consistent routines and encouraging self-help, to ensuring safety and promoting mindful connection, these evidence-based tips support toddler development across all domains—creating meaningful relationships and fostering lifelong resilience. References CDC (2025a) Positive Parenting Tips: Toddlers (1–2 years old). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/child-development/positive-parenting-tips/toddlers-1-2-years.html (Accessed: 14 August 2025). CDC (2025b) Positive Parenting Tips: Toddlers (2–3 years old). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/child-development/positive-parenting-tips/toddlers-2-3-years.html (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Happiest Baby (n.d.) 3 Positive Parenting Tricks to Turn Your Toddler’s Behavior. Available at: https://www.happiestbaby.com/blogs/toddler/positive-parenting-tricks (Accessed: 14 August 2025). HealthyChildren.org (n.d.) Toddler Parenting. Available at: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/growing-healthy/Pages/toddler-parenting.aspx (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Michigan.gov (n.d.) Parenting Toddlers. Available at: https://www.michigan.gov/mikidsmatter/parents/toddler/parenting (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Parents.com (2015) 50 Easy Ways to Be a Fantastic Parent. Available at: https://www.parents.com/parenting/better-parenting/advice/ways-to-be-fantastic-parent/ (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Parents.com (2025) Why Type C Parenting Might Be the Secret to Better Family Vacations. Available at: https://www.parents.com/type-c-parenting-might-be-the-secret-to-better-family-vacations-11785210 (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Raising Children (2024a) Toddlers (1–3 years). Available at: https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Raising Children (2024b) Toddler development at 2–3 years. Available at: https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/development/development-tracker-1-3-years/2-3-years (Accessed: 14 August 2025). The Sun (2023) Seven brain-boosting tips for those little moments together with your toddler. Available at: https://www.thesun.ie/health/12291819/toddler-learning-little-moments-start-for-life-ohid-government/ (Accessed: 14 August 2025). The Sun (2025a) I stopped screen time for my three-year-old daughter & there’s been three HUGE changes in her behaviour. Available at: https://www.thesun.co.uk/fabulous/36272096/screen-time-kids-ban-behaviour-changes/ (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Times of India (2025a) Mindful parenting: 5 ways to stay present when life gets hectic. Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/parenting/parentology/parenting-and-you/mindful-parenting-5-ways-to-stay-present-when-life-gets-hectic/articleshow/123302363.cms (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Verywell Family (2017) An Overview of Toddlers. Available at: https://www.verywellfamily.com/toddlers-4157379 (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Wikipedia (2021) Reflective parenting. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reflective_parenting (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Wikipedia (2025a) Positive discipline. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Positive_discipline (Accessed: 14 August 2025). Wikipedia (2025b) Infant and toddler safety. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infant_and_toddler_safety … Read more