The study of art movements is one of the most fundamental aspects of art scholarship, as it helps to trace the evolution of artistic thought and practice within distinct historical and cultural contexts. Each movement represents a collective response to prevailing social, political, technological, and intellectual developments, revealing how art both shapes and is shaped by the times. From the Renaissance to Modernism and beyond, art movements have served as mirrors of human experience and as catalysts for cultural transformation.

The Renaissance (14th –17th Centuries)

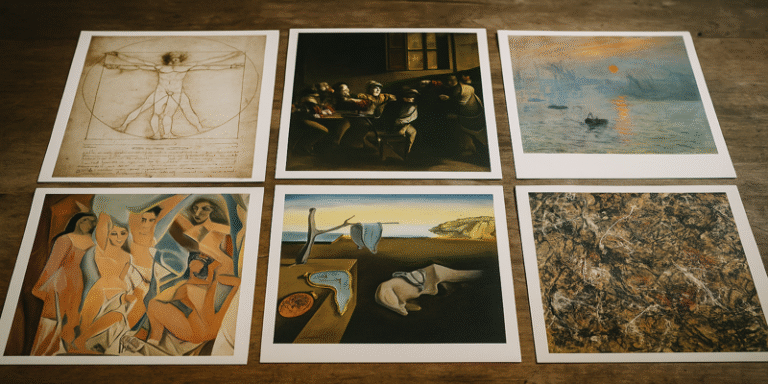

The Renaissance marked a pivotal shift in European art and thought, characterised by a revival of classical ideals, humanism, and the pursuit of scientific perspective. Originating in Italy and later spreading across Europe, this movement represented a renewed interest in antiquity and the potential of human intellect. Renaissance artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael sought to harmonise artistic skill with intellectual inquiry, bridging art, science, and philosophy (Hauser, 2005).

Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (c.1490) epitomises this synthesis, demonstrating a profound understanding of human anatomy and mathematical proportion. Similarly, Michelangelo’s David (1501–1504) reflects both classical influence and humanist ideals, portraying humanity as noble, rational, and divinely inspired. According to Edgerton (2009), the development of linear perspective by artists such as Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti revolutionised visual representation, allowing for more realistic spatial depth. Thus, the Renaissance not only redefined artistic standards but also reinforced the belief in human capacity and rationality.

The Baroque (17th Century)

Emerging in the early 17th century, the Baroque movement contrasted the calm balance of the Renaissance with dram, grandeur, and emotional intensity. Rooted in the religious and political turbulence of the Counter-Reformation, Baroque art aimed to evoke awe and devotion, particularly within the context of Catholic Europe (Freeland, 2003).

Artists such as Caravaggio, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and Peter Paul Rubens employed theatrical lighting, dynamic compositions, and ornate detail to heighten the viewer’s emotional engagement. Caravaggio’s The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600), for instance, employs chiaroscuro (the contrast between light and dark) to create dramatic tension and focus attention on divine revelation. As Gombrich (1995) argues, the Baroque style served as a powerful visual language of persuasion, reflecting the Church’s effort to reaffirm its authority during a time of religious fragmentation.

Moreover, Baroque architecture, seen in Bernini’s St Peter’s Baldachin (1623–1634) and Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1638–1646), exemplifies how art and design were used to manipulate space and emotion, guiding the viewer’s gaze toward the spiritual and the sublime.

The Impressionist Movement (19th Century)

In stark contrast to the grandiosity of earlier movements, Impressionism in the late 19th century reflected the modern world’s shifting social and technological landscapes. Originating in France, this movement emerged as a reaction against the rigid academic standards of the École des Beaux-Arts and the Salon system. Impressionist artists such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas sought to capture the fleeting effects of light, atmosphere, and perception, portraying contemporary life with spontaneity and immediacy (Hatt and Klonk, 2006).

Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872), which inspired the term “Impressionism”, exemplifies the movement’s emphasis on optical experience over narrative content. According to Tinterow (2008), the Impressionists were influenced by scientific studies of colour theory and the invention of portable paint tubes, which allowed artists to work en plein air (outdoors) and observe natural light directly. Degas’s depictions of ballet dancers and modern women reveal a fascination with urban life and movement, while Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881) conveys the warmth and intimacy of bourgeois leisure.

Despite early criticism for their unfinished appearance, Impressionist works came to redefine the relationship between art and modernity, emphasising subjective experience and visual perception over idealised representation (Callen, 2000).

Modernism and Avant-Garde Movements (20th Century)

The 20th century witnessed a radical departure from traditional artistic conventions with the rise of Modernism and a series of avant-garde movements, including Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism. These movements collectively sought to rethink the purpose of art, exploring abstraction, emotion, and the subconscious as central modes of expression (Belting, 2003).

Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, fragmented form and space to represent multiple perspectives simultaneously. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) challenged conventional representation through its geometric distortion and incorporation of African art influences (Chilvers, 2004). This movement marked a decisive shift toward conceptual abstraction, emphasising the artist’s vision rather than optical realism.

Surrealism, influenced by Sigmund Freud’s theories of the unconscious, emerged in the 1920s as an exploration of dreams, desire, and the irrational. Artists such as Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, and Max Ernst employed symbolism and juxtaposition to challenge rational perception. Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931), with its melting clocks, symbolises the fluidity of time and the instability of reality. As Breton (1969) argued in the Surrealist Manifesto, art could become a means of liberating the mind from social and psychological constraints.

Later, Abstract Expressionism, particularly in post-war America, embodied the emotional and existential crises of the modern age. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko rejected representation altogether, using gesture, colour, and scale to express the inner self (Doss, 2002). Pollock’s drip paintings, such as Number 1A, 1948, emphasise the process of creation as an act of spontaneity and energy, while Rothko’s vast colour fields evoke transcendence and introspection. These movements collectively underscored the shift toward individualism, abstraction, and experimentation in 20th-century art.

Art Movements as Cultural Reflection

Art movements are more than stylistic classifications; they function as cultural barometers, reflecting societal changes and intellectual currents. As Edwards (1999) notes, the evolution of artistic styles corresponds with broader transformations in philosophy, science, and politics. For instance, the Industrial Revolution and urbanisation inspired new subjects in Realism and Impressionism, while the trauma of World War I gave rise to Dadaism and Surrealism, which expressed disillusionment and rebellion against rational order (Hopkins, 2004).

In contemporary contexts, movements such as Postmodernism, Conceptual Art, and Street Art continue this tradition, challenging the boundaries between high art and popular culture. Artists like Banksy and Barbara Kruger, for example, use irony and text to critique consumerism and authority, demonstrating the enduring capacity of art to provoke critical reflection (Lewisohn, 2008).

Ultimately, the historical study of art movements reveals the dialogue between art and society—a continuous negotiation between tradition and innovation, order and disruption, and the individual and the collective. Each movement, whether Renaissance humanism or Abstract Expressionist introspection, reflects a particular moment in humanity’s ongoing quest for meaning and expression.

References

Belting, H. (2003) Art History After Modernism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Breton, A. (1969) Manifestoes of Surrealism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Callen, A. (2000) Impressionism. London: Phaidon Press.

Chilvers, I. (2004) The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Doss, E. (2002) Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Edgerton, S. (2009) The Mirror, the Window, and the Telescope: How Renaissance Linear Perspective Changed Our Vision of the Universe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Edwards, S. (1999) Art and Its Histories: A Reader. London: Yale University Press.

Freeland, C. (2003) Art Theory: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gombrich, E.H. (1995) The Story of Art. London: Phaidon Press.

Hauser, A. (2005) The Social History of Art. London: Routledge.

Hatt, M. and Klonk, C. (2006) Art History: A Critical Introduction to Its Methods. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Hopkins, D. (2004) After Modern Art: 1945–2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewisohn, C. (2008) Street Art: The Graffiti Revolution. London: Tate Publishing.

Tinterow, G. (2008) Origins of Impressionism. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.