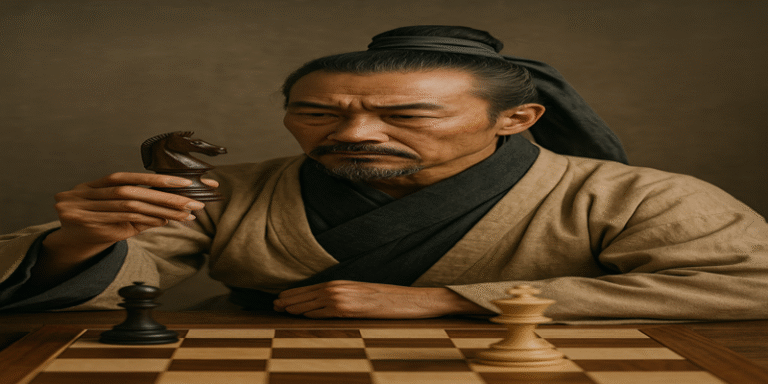

Strategic thinking has been a cornerstone of leadership, management, and conflict resolution for centuries. Few works have influenced the field as profoundly as Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, written over 2,500 years ago. Despite its origins in military strategy, Sun Tzu’s philosophy transcends warfare and applies to modern-day domains such as business, politics, and personal development. This essay critically examines Sun Tzu’s seven rules for strategic thinking—knowing your enemy, knowing yourself, deception, adaptation, timing, using strength against weakness, and winning without fighting—and explores their contemporary relevance with examples from real-world practice.

1.0 Know Your Enemy

Sun Tzu asserted that “if you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles” (The Art of War, cited in Griffith, 2005). Understanding competitors is central to both military and business contexts. This entails studying an opponent’s strengths, weaknesses, intentions, and patterns, which allows anticipation of their next move.

In business strategy, this principle manifests in competitive intelligence. For instance, Apple’s continuous analysis of competitors like Samsung has allowed it to anticipate technological trends and position itself effectively in the smartphone market (Grant, 2019). Similarly, in military history, the Allies’ success in World War II’s D-Day invasion hinged on detailed knowledge of German defences and movements (Keegan, 1989).

Modern research supports this. According to Fleisher and Bensoussan (2015), systematic competitor analysis enhances decision-making and minimises uncertainty, giving firms an edge in dynamic environments.

2.0 Know Yourself

Equally important is self-awareness. Sun Tzu emphasised clarity about one’s own resources, limitations, and capabilities. In management, this translates into organisational self-assessment.

For example, Toyota’s rise in the automotive industry was not due to outspending competitors but rather recognising its own strengths in lean manufacturing and continuous improvement (Kaizen) (Ohno, 1988). By leveraging these capabilities, Toyota became synonymous with quality and efficiency.

In psychology, self-knowledge is equally critical. Research by Silvia and O’Brien (2004) highlights how individuals with greater self-insight demonstrate better adaptability and decision-making. This reinforces Sun Tzu’s notion that understanding internal strengths and limitations enhances chances of success before any conflict begins.

3.0 Deception

Sun Tzu famously declared that “all warfare is based on deception” (The Art of War, cited in Griffith, 2005). Deception in strategy involves appearing weak when strong, hiding true intentions, and misleading opponents into mistakes.

In military history, one of the most striking examples is the Battle of Hastings (1066), where William the Conqueror used feigned retreats to lure Harold’s forces into disarray (Abbott, 2005). In business, companies often deploy strategic signalling to mislead competitors. For instance, Microsoft has been known to announce “vapourware”—products under development that may never launch—to discourage rivals from investing in similar innovations (Campbell-Kelly, 2003).

However, deception must be handled carefully. Excessive reliance on it can damage reputation and trust. Ethical considerations in management literature warn that deceptive strategies may yield short-term gains but harm long-term stakeholder relationships (Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014).

4.0 Adaptation

Sun Tzu advised that strategy should “flow like water,” highlighting the need for flexibility and resilience. This involves adjusting plans as conditions change and avoiding rigidity.

In modern strategic management, this aligns with the concept of dynamic capabilities—the ability of firms to integrate, build, and reconfigure competencies to address rapidly changing environments (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997). Netflix illustrates this principle well. Originally a DVD rental service, it adapted to shifting consumer behaviour and technological changes by transitioning to streaming and later to original content production.

In military terms, General Norman Schwarzkopf’s strategy in the 1991 Gulf War exemplified adaptation. Coalition forces avoided a direct frontal assault on entrenched Iraqi forces and instead executed a rapid flanking manoeuvre, demonstrating flexibility in operational planning (Atkinson, 1993).

5.0 Timing

Patience and timing are central to effective strategy. Sun Tzu stressed the importance of waiting until the enemy is tired, striking in moments of weakness, and using time as a weapon.

In the financial world, Warren Buffett’s investment philosophy embodies this principle. Known for waiting patiently until the right opportunities arise, Buffett leverages timing by investing in undervalued companies during market downturns (Hagstrom, 2013).

In sports, timing is equally crucial. In cricket, for example, batters succeed not by brute force but by striking the ball at the right moment, demonstrating Sun Tzu’s timeless insight into the role of patience and precision.

6.0 Use Strength Against Weakness

Sun Tzu argued that power is most effective when directed at an opponent’s vulnerabilities. Rather than engaging in direct confrontation, successful strategists exploit the unexpected path.

In business, Southwest Airlines exemplified this by targeting short-haul, low-cost routes ignored by major airlines. By focusing on a neglected market segment, Southwest gained a strong competitive position (Gittell, 2003). Similarly, insurgent groups in asymmetric warfare often exploit vulnerabilities in larger, more powerful militaries by avoiding direct confrontations and instead striking weak points (Kaldor, 2013).

This principle highlights the efficiency of aligning one’s strengths with an adversary’s weaknesses rather than engaging in costly head-to-head competition.

7.0 Win Without Fighting

Perhaps the most profound of Sun Tzu’s insights is that “the supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.” Victory without destruction involves breaking plans before they unfold, persuasion without violence, and achieving success through influence rather than force.

Diplomacy and negotiation embody this rule. For example, the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) was resolved not through war but through careful negotiation and compromise, preventing nuclear catastrophe (Allison & Zelikow, 1999).

In business, Google’s dominance in search has often prevented direct competition from emerging, as rivals recognise the futility of challenging such a powerful incumbent. Instead, companies like Amazon and Facebook focused on different domains, illustrating how influence can deter conflict.

Sun Tzu’s seven rules for strategic thinking remain profoundly relevant in today’s complex world. From military campaigns and corporate strategies to individual decision-making, his teachings highlight the timeless value of knowledge, adaptability, timing, and restraint. By integrating insights from historical examples and modern theories of strategy and management, it becomes clear that Sun Tzu’s wisdom offers enduring lessons for navigating competitive environments.

The application of these rules across diverse fields underscores their universality. Whether in business boardrooms, political negotiations, or personal challenges, the art of strategy lies not in brute force but in the intelligent alignment of strengths, opportunities, and timing. Ultimately, the most powerful victory is one achieved without conflict.

References

Abbott, J. (2005). The Battle of Hastings 1066. London: Tempus.

Allison, G. & Zelikow, P. (1999). Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

Atkinson, R. (1993). Crusade: The Untold Story of the Persian Gulf War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Campbell-Kelly, M. (2003). From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Carroll, A. & Buchholtz, A. (2014). Business and Society: Ethics, Sustainability and Stakeholder Management. 9th ed. Boston: Cengage.

Fleisher, C. & Bensoussan, B. (2015). Business and Competitive Analysis. 2nd ed. London: Pearson.

Gittell, J.H. (2003). The Southwest Airlines Way. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Grant, R.M. (2019). Contemporary Strategy Analysis. 10th ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Griffith, S.B. (2005). Sun Tzu: The Art of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hagstrom, R.G. (2013). The Warren Buffett Way. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Kaldor, M. (2013). New and Old Wars. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Keegan, J. (1989). The Second World War. London: Hutchinson.

Ohno, T. (1988). Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. Portland: Productivity Press.

Silvia, P.J. & O’Brien, M.E. (2004). “Self-awareness and constructive functioning: Revisiting ‘the human dilemma.’” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(4), pp. 475–489.

Teece, D., Pisano, G. & Shuen, A. (1997). “Dynamic capabilities and strategic management.” Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), pp. 509–533.