Supply Chain Management: Concepts, Practices, and Contemporary Developments

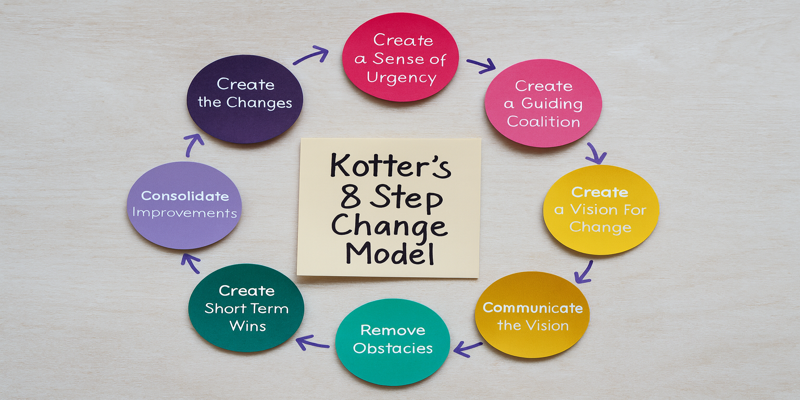

Supply Chain Management (SCM) refers to the coordination, integration, and optimisation of activities involved in sourcing, procurement, production, logistics, and distribution, ensuring that goods and services flow smoothly from suppliers to end consumers (Christopher, 2016). The ultimate aim of SCM is to enhance customer value, improve efficiency, and build sustainable competitive advantage (Chopra & Meindl, 2019). With increasing globalisation, the rapid advancement of digital technologies, and the rise of consumer expectations, SCM has evolved into a critical function that determines organisational competitiveness. For instance, Amazon’s success is attributed largely to its sophisticated logistics and distribution networks, which enable faster delivery and higher levels of customer satisfaction compared to traditional retailers (Tan, 2001). 1.0 Evolution of Supply Chain Management Historically, SCM was viewed as an extension of purchasing and logistics functions. In the 1990s, the term “supply chain management” gained prominence as organisations began adopting a more integrated approach that included suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and retailers in a single strategic framework (Handfield et al., 2009). According to Tan (2001), SCM shifted the focus from cost reduction alone to value creation, emphasising responsiveness, flexibility, and long-term partnerships. This transition marked the rise of strategic sourcing, global procurement, and just-in-time (JIT) production systems, all of which remain central in modern SCM practice. 2.0 Core Components of SCM SCM comprises several interconnected functions that together ensure effective operations across the value chain. 2.1 Sourcing and Procurement Sourcing involves identifying, evaluating, and selecting suppliers, while procurement relates to acquiring the necessary materials and services. Effective procurement ensures cost efficiency, quality consistency, and supply reliability (Lysons & Farrington, 2006). For example, Toyota’s lean supply chain relies on long-term supplier relationships, which reduce transaction costs and ensure reliable delivery schedules (Schiele, 2018). Strategic sourcing techniques, such as dual sourcing and e-procurement systems, have emerged as powerful tools to reduce risks and improve agility (Amorim & Almada-Lobo, 2014). 2.2 Production Production planning coordinates the transformation of raw materials into finished goods. Effective production relies on demand forecasting, capacity planning, and inventory control (Vidal & Goetschalckx, 1997). Companies such as Dell pioneered build-to-order models, reducing inventory holding costs while increasing responsiveness to customer preferences (Erengüç, Simpson & Vakharia, 1999). 2.3 Distribution and Logistics Distribution management ensures that products reach customers at the right time and in the right condition. Logistics functions, including transportation, warehousing, and last-mile delivery, play a vital role in customer satisfaction (Park, 2005). Amazon’s Prime delivery service illustrates how distribution efficiency can differentiate a company in competitive markets. 3.0 Globalisation and Digital Transformation The increasing globalisation of trade has extended supply chains across continents, making them more complex and vulnerable to risks. Companies now manage global sourcing networks, balancing cost advantages with challenges such as currency fluctuations, political instability, and sustainability pressures (Zeng, 2003). Furthermore, digital technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), blockchain, and the Internet of Things (IoT) have revolutionised SCM. For example, blockchain ensures supply chain transparency by providing immutable records of transactions, while IoT-enabled sensors improve real-time tracking of shipments (Di Pasquale, Nenni & Riemma, 2020). 4.0 Sustainability in Supply Chain Management Sustainability has emerged as a strategic priority in SCM. Companies face growing pressure from governments, consumers, and stakeholders to adopt environmentally responsible and ethically sound practices (Andersen & Rask, 2003). Green supply chain management (GSCM) integrates environmental considerations into procurement, production, and distribution decisions. For instance, Unilever has committed to reducing carbon emissions across its supply chain by sourcing renewable energy and minimising waste (Golini & Kalchschmidt, 2011). 5.0 Challenges in Supply Chain Management Despite advancements, SCM faces several pressing challenges: Supply chain disruptions: Events such as the COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in global supply chains, causing widespread shortages (Gundlach, Bolumole & Eltantawy, 2006). Rising consumer expectations: Customers demand faster delivery and greater personalisation, forcing firms to innovate (Giunipero & Brand, 1996). Balancing cost and resilience: Organisations must strike a balance between efficiency (lean operations) and resilience (risk mitigation strategies) (Zeng, 2003). Integration of digital tools: While digitalisation offers opportunities, it requires significant investment and change management (Ross, 2015). 6.0 Case Examples of Effective SCM Zara – The fashion retailer has developed an agile supply chain, enabling it to move designs from concept to store shelves in as little as two weeks. This rapid responsiveness provides a competitive edge in the fast fashion industry (Simpson & Vakharia, 1999). Apple – Apple’s supply chain combines global sourcing, just-in-time production, and strategic supplier partnerships, allowing it to scale operations efficiently while maintaining quality (Benton, 2020). Walmart – Walmart leverages advanced inventory management systems and distribution technologies to maintain low costs and high product availability, exemplifying the integration of technology into SCM (Monczka et al., 2009). In today’s interconnected and competitive marketplace, Supply Chain Management has become a cornerstone of organisational strategy. By integrating sourcing, procurement, production, and distribution, firms can enhance efficiency, minimise costs, and create sustainable value. With increasing globalisation, technological disruption, and sustainability imperatives, SCM is evolving from a traditional operational function into a strategic enabler of competitive advantage. Organisations that embrace digital innovation, build resilient networks, and commit to sustainability will lead in the next era of supply chain excellence. References Amorim, P. & Almada-Lobo, B. (2014). Combining supplier selection and production-distribution planning in food supply chains. Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, Elsevier. Andersen, P.H. & Rask, M. (2003). Supply chain management: new organisational practices for changing procurement realities. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 9(2), pp.83-95. Benton, W.C. (2020). Purchasing and Supply Chain Management. McGraw-Hill. Chopra, S. & Meindl, P. (2019). Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation. Pearson. Christopher, M. (2016). Logistics & Supply Chain Management. Pearson UK. Di Pasquale, V., Nenni, M.E. & Riemma, S. (2020). Order allocation in purchasing management. International Journal of Production Research, 58(13), pp.3942–3962. Erengüç, Ş.S., Simpson, N.C. & Vakharia, A.J. (1999). Integrated production/distribution planning in supply chains. European Journal of Operational Research, 115(2), pp.219–236. Giunipero, L.C. & Brand, R.R. (1996). Purchasing’s role in supply chain management. International Journal of Logistics Management, 7(1), pp.29-38. Golini, R. & Kalchschmidt, M. (2011). Moderating the impact … Read more