Sociology is the systematic study of society, social institutions, and the relationships among individuals within those institutions. Originating in the 19th century through the work of classical theorists like Karl Marx, Émile Durkheim, and Max Weber, sociology has evolved into a diverse and interdisciplinary field. It addresses complex societal issues such as inequality, identity, culture, power, and social change. In academic settings, sociology is typically divided into key modules that help structure the field and guide students through its core areas. This article provides an overview of several fundamental study modules in sociology, including social theory, research methods, social stratification, culture and identity, globalisation, and contemporary social issues.

1.0 Social Theory

Social theory forms the intellectual backbone of sociology. It offers conceptual frameworks for analysing how societies function and change. Classical social theory, which includes the work of Marx, Durkheim, and Weber, remains foundational. Marx focused on class conflict and economic structures, Durkheim emphasised social cohesion and collective consciousness, while Weber explored rationalisation and the role of bureaucracy (Giddens & Sutton, 2021).

Modern sociological theory incorporates structural functionalism, conflict theory, symbolic interactionism, and postmodern perspectives. Structural functionalism views society as a complex system whose parts work together (Parsons, 1951), whereas conflict theory emphasises power struggles and inequality. Symbolic interactionism, championed by Mead and Blumer, focuses on micro-level social interactions (Blumer, 1969). Postmodern theorists like Bauman and Foucault question grand narratives and highlight the fragmented, media-saturated nature of contemporary life (Bauman, 2000; Foucault, 1977).

2.0 Research Methods in Sociology

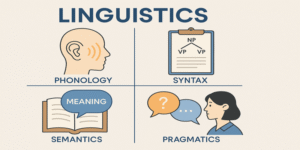

Understanding society scientifically requires robust methodological tools. The research methods module equips students with quantitative and qualitative techniques for data collection and analysis. Quantitative methods include surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis, enabling researchers to uncover patterns and generalise findings. Qualitative methods—such as interviews, ethnography, and content analysis—offer in-depth insights into social meanings and practices (Bryman, 2016).

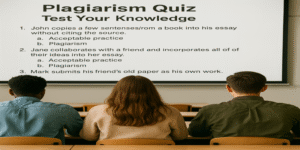

Ethics is a vital concern in sociological research. Researchers must consider informed consent, confidentiality, and the potential impact of their work on participants (Punch, 2014). Methodological reflexivity, where researchers acknowledge their influence on the research process, is also increasingly emphasised.

3.0 Social Stratification and Inequality

Stratification refers to the hierarchical arrangement of individuals in society based on characteristics like class, gender, race, and age. This module examines how inequalities are produced, maintained, and challenged. Karl Marx’s theory of class conflict remains a critical point of departure, proposing that economic divisions drive social dynamics. Max Weber added dimensions of status and power, showing that social hierarchy is multifaceted (Weber, 1978).

Modern sociologists like Pierre Bourdieu explore the role of cultural capital and habitus in maintaining class distinctions (Bourdieu, 1986). Feminist sociologists highlight gender inequalities, while intersectionality examines how multiple identities (e.g., race, gender, class) intersect to produce unique experiences of oppression (Crenshaw, 1991).

Contemporary issues such as the gig economy, housing crises, and educational disparities are also studied under this module to understand the lived realities of inequality in modern societies (Dorling, 2015).

4.0 Culture and Identity

Culture and identity are central to understanding social life. Culture includes shared beliefs, values, practices, and artefacts, while identity refers to how individuals see themselves and are perceived by others. This module explores how culture is produced, consumed, and transformed over time.

Symbolic interactionism plays a key role here, focusing on how identities are formed through social interaction. Stuart Hall’s work on cultural identity and representation is particularly influential, emphasising the fluid and contested nature of identity in a globalised world (Hall, 1996).

The module also explores subcultures, popular culture, and the role of the media in shaping perceptions. It considers how identities based on gender, ethnicity, sexuality, and nationality are constructed and contested in different contexts.

5.0 Globalisation and Social Change

Globalisation refers to the increasing interconnectedness of societies through economic, political, technological, and cultural exchange. This module examines the implications of globalisation on local and global scales. Scholars such as Anthony Giddens argue that globalisation reshapes everyday life and social institutions, creating both opportunities and challenges (Giddens, 2002).

Topics covered include transnational migration, environmental change, global inequality, and the impact of global media. Theories of globalisation, such as world-systems theory and global risk society, provide analytical tools for understanding these dynamics (Wallerstein, 2004; Beck, 1992).

The module also examines resistance to globalisation, including social movements, localism, and the reassertion of national identities in the face of perceived global homogenisation.

6.0 Contemporary Social Issues

This module addresses pressing social problems such as crime, deviance, health, education, and family life. Students explore how these issues are socially constructed and understood through various sociological lenses. For instance, crime and deviance are examined through functionalist perspectives (Durkheim), labelling theory (Becker), and critical criminology.

Health inequalities are studied with regard to class, ethnicity, and access to healthcare, while educational sociology explores how schooling reproduces or challenges social inequality (Ball, 2003). The sociology of the family considers how familial roles and structures have evolved, particularly in response to shifting gender norms and legal changes such as the legalisation of same-sex marriage.

This module is often interdisciplinary, drawing from economics, psychology, and political science to explore the multifaceted nature of social issues.

Sociology is a dynamic and multi-layered discipline that equips students with the conceptual and analytical tools to understand and engage with the complexities of modern society. The key modules discussed—social theory, research methods, social stratification, culture and identity, globalisation, and contemporary issues—form the core of sociological education. Each module offers unique perspectives and insights, allowing students to critically examine the world around them and consider possibilities for social change.

Through studying these modules, students not only gain academic knowledge but also develop a sociological imagination—a term coined by C. Wright Mills (1959)—which enables them to connect personal experiences with broader social structures. In an increasingly complex and interconnected world, the study of sociology remains more relevant than ever.

References

Ball, S. J. (2003) Class Strategies and the Education Market: The Middle Classes and Social Advantage. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Bauman, Z. (2000) Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Beck, U. (1992) Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage.

Blumer, H. (1969) Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Bourdieu, P. (1986) ‘The Forms of Capital’, in Richardson, J. (ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York: Greenwood, pp. 241–258.

Bryman, A. (2016) Social Research Methods. 5th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1991) ‘Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Colour’, Stanford Law Review, 43(6), pp. 1241–1299.

Dorling, D. (2015) Inequality and the 1%. London: Verso.

Foucault, M. (1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin.

Giddens, A. (2002) Runaway World: How Globalisation is Reshaping Our Lives. London: Profile Books.

Giddens, A. and Sutton, P. W. (2021) Sociology. 10th edn. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hall, S. (1996) ‘Cultural Identity and Diaspora’, in Mongia, P. (ed.) Contemporary Postcolonial Theory: A Reader. London: Arnold, pp. 110–121.

Mills, C. W. (1959) The Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press.

Parsons, T. (1951) The Social System. London: Routledge.

Punch, K. F. (2014) Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. 3rd edn. London: Sage.

Wallerstein, I. (2004) World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction. Durham: Duke University Press.

Weber, M. (1978) Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Berkeley: University of California Press.