Meditation, once a spiritual practice deeply rooted in Eastern traditions, has emerged as a mainstream tool for enhancing psychological well-being in the modern world. From university campuses to corporate offices, meditation is increasingly advocated as a simple yet powerful technique for stress reduction, emotional balance, and even cognitive enhancement. But what exactly is meditation? Why is it gaining such global popularity? This article explores the nature of meditation, its types, psychological and physiological benefits, and common misconceptions, offering a balanced perspective based on scientific and scholarly evidence.

What is Meditation?

Meditation can be defined as a set of mental practices that train attention and awareness to achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm state. According to Goleman and Davidson (2017), meditation is not just about relaxation but involves systematic training of the mind that can induce lasting changes in brain function and behaviour.

Historically, meditation is a core component of religious traditions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Taoism. However, in recent decades, it has been secularised and studied scientifically as a psychological technique for promoting health and well-being (Walsh & Shapiro, 2006).

Types of Meditation

There are many forms of meditation, but most fall into two broad categories:

1.0 Focused-Attention Meditation (FAM)

This involves concentrating on a single object—like the breath, a mantra, or a candle flame. If the mind wanders, the practitioner gently brings it back to the object of focus (Lutz et al., 2008).

2.0 Open-Monitoring Meditation (OMM)

Rather than focusing on a specific object, OMM entails being aware of all aspects of experience—thoughts, emotions, sounds—without judgment or attachment (Tang et al., 2015).

Modern adaptations include:

Mindfulness Meditation, derived from Buddhist traditions, emphasising non-judgmental awareness of the present moment.

Transcendental Meditation, using a mantra to transcend ordinary thought (Roth, 2013).

Loving-Kindness Meditation, which involves cultivating feelings of compassion and goodwill towards others (Fredrickson et al., 2008).

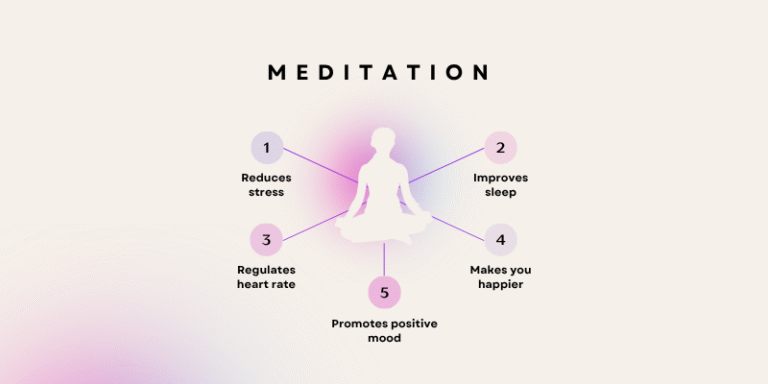

Scientific Benefits of Meditation

1.0 Stress Reduction

Numerous studies highlight meditation’s role in reducing stress. A meta-analysis by Goyal et al. (2014) involving over 3,500 participants found that mindfulness meditation significantly reduces stress, anxiety, and depression. This is likely due to meditation’s ability to downregulate the sympathetic nervous system, which governs the body’s stress response (Hölzel et al., 2011).

2.0 Mental Health Improvement

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been shown to be effective in treating various psychological conditions, including generalised anxiety disorder, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Khoury et al., 2013). Unlike medication, MBIs have minimal side effects and encourage long-term behavioural change.

3.0 Brain Structure and Function

Meditation can literally change the brain. Studies using MRI scans have shown that regular meditation is associated with increased grey matter density in areas involved in learning, memory, emotion regulation, and perspective-taking (Lazar et al., 2005). Long-term meditators also exhibit greater connectivity in the default mode network (DMN), which is related to self-awareness and introspection (Brewer et al., 2011).

4.0 Physical Health

The benefits are not purely psychological. Meditation has been linked to improvements in blood pressure, immune function, and even cellular ageing. Black and Slavich (2016) reported that meditation may downregulate genes involved in inflammation, which is associated with many chronic diseases.

How Meditation Works

Meditation appears to work by enhancing meta-awareness—the ability to notice and observe mental processes. It also trains cognitive flexibility, allowing individuals to disengage from harmful thought patterns more easily. Additionally, meditation promotes activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, sometimes called the “rest and digest” system, which induces calm and recovery (Tang, Hölzel & Posner, 2015).

Common Misconceptions About Meditation

Despite its popularity, meditation is surrounded by myths:

- “Meditation is about emptying the mind.”

This is misleading. The goal is not to stop thinking, but to observe thoughts without being controlled by them.

- “Only spiritual people can meditate.”

While meditation has spiritual roots, modern practice is secular and evidence-based. Anyone can benefit from it, regardless of belief.

- “Meditation takes years to be effective.”

Research indicates that even short-term practice—around 10 minutes daily for a few weeks—can yield measurable benefits (Zeidan et al., 2010).

How to Start Meditating

Starting a meditation practice can be simple:

1.0 Set aside 5–10 minutes each day in a quiet space.

2.0 Sit comfortably with a straight posture.

3.0 Focus on the breath—inhaling and exhaling slowly.

4.0 Notice distractions and gently return attention to the breath.

5.0 Use guided apps such as Headspace or Insight Timer for support.

Consistency is more important than duration. Over time, the mind becomes more trained, and benefits accrue.

Meditation in Education and Healthcare

Meditation is increasingly incorporated into school and university curricula to support student well-being. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is now common in healthcare settings and supported by organisations like the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for treating depression (NICE, 2009).

Universities such as Oxford, Cambridge, and UCL offer mindfulness courses, and studies report improvements in students’ concentration, emotional regulation, and academic performance (Galante et al., 2018).

Meditation is far more than a trend—it is a scientifically validated, accessible, and cost-effective tool for improving mental and physical health. Whether you are a student seeking focus, a worker battling stress, or a curious individual exploring inner peace, meditation offers something meaningful. With consistent practice and an open mind, meditation can become a transformative part of daily life.

References

Black, D. S. & Slavich, G. M. (2016). Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1373(1), pp.13–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12998

Brewer, J. A., et al. (2011). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. NeuroImage, 57(5), pp.1524–1533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.061

Fredrickson, B. L., et al. (2008). Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), pp.1045–1062. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013262

Galante, J., et al. (2018). A mindfulness-based intervention to increase resilience to stress in university students (the Mindful Student Study): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Public Health, 3(2), pp.e72–e81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30231-1

Goleman, D. & Davidson, R. J. (2017). Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body. London: Penguin Books.

Goyal, M., et al. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), pp.357–368. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018

Hölzel, B. K., et al. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), pp.537–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671.

Khoury, B., et al. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), pp.763–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005.

Lazar, S. W., et al. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. NeuroReport, 16(17), pp.1893–1897. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wnr.0000186598.66243.19

Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(4), pp.163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005

NICE. (2009). Depression in adults: recognition and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. [Online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90

Roth, R. (2013). Strength in Stillness: The Power of Transcendental Meditation. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Tang, Y.-Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), pp.213–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916.

Walsh, R., & Shapiro, S. L. (2006). The meeting of meditative disciplines and Western psychology. American Psychologist, 61(3), pp.227–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.227.

Zeidan, F., et al. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), pp.597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014.