In contemporary society, where stress, sedentary lifestyles and digital overload are increasingly common, the concept of the spa has evolved into more than a luxury indulgence. Modern spas function as structured environments dedicated to promoting health, relaxation and holistic well-being. Rooted in ancient bathing traditions from Roman thermae to Turkish hammams, spas now integrate evidence-based therapies designed to enhance both physical and psychological health (Cohen and Bodeker, 2008).

According to the International Spa Association (ISPA, 2023), a spa is a facility devoted to overall well-being through a variety of professional services that encourage renewal of mind, body and spirit. From therapeutic massage to hydrotherapy and wellness programmes, spas provide multidimensional interventions that support stress reduction, musculoskeletal health and emotional balance.

1.0 Massage Therapy: Relieving Tension and Promoting Circulation

One of the most recognised spa treatments is massage therapy, involving the manipulation of muscles and soft tissues to relieve tension and improve circulation. Field (2016) notes that massage reduces cortisol levels while increasing serotonin and dopamine, thereby improving mood and reducing anxiety.

Common forms include:

- Swedish massage – characterised by gentle, rhythmic strokes promoting relaxation.

- Deep tissue massage – targeting deeper muscle layers to relieve chronic tension.

- Hot stone massage – using heated stones to enhance muscle relaxation.

- Aromatherapy massage – combining essential oils with massage techniques to support emotional wellbeing.

Clinical research supports massage for reducing symptoms of stress, anxiety and chronic pain (Moyer, Rounds and Hannum, 2004). For example, individuals experiencing work-related stress may benefit from regular massage sessions to alleviate muscular stiffness and improve sleep quality.

2.0 Facials and Dermatological Benefits

Facial treatments are designed to cleanse, exfoliate and nourish the skin. Dermatological research highlights the importance of cleansing and hydration in maintaining skin barrier function (Draelos, 2012). Facials typically involve steaming, exfoliation, mask application and moisturising, tailored to individual skin types.

Beyond cosmetic enhancement, facials can improve skin texture, circulation and hydration, contributing to self-confidence and psychological wellbeing. The British Association of Dermatologists (2022) emphasises that appropriate skincare supports both skin health and self-esteem.

3.0 Body Treatments: Detoxification and Rejuvenation

Body treatments include scrubs, wraps, mud applications and exfoliation therapies. Exfoliation removes dead skin cells, promoting cellular renewal and smoother skin texture (Baumann, 2015).

Mud and mineral treatments, historically associated with balneotherapy, may contribute to improved skin condition and reduced joint discomfort (Nasermoaddeli and Kagamimori, 2005). While claims of “detoxification” are sometimes overstated, heat-based therapies can enhance circulation and support relaxation.

For example, individuals with mild muscle soreness may find that body wraps combined with massage reduce perceived tension.

4.0 Hydrotherapy and Spa Baths

Hydrotherapy, or water-based therapy, has longstanding therapeutic roots. Warm water immersion relaxes muscles, improves circulation and reduces joint stiffness (Becker, 2009). Facilities such as hot tubs, saunas and steam rooms promote vasodilation and temporary stress relief.

Hydrotherapy has demonstrated benefits in managing musculoskeletal conditions and enhancing relaxation (Bender et al., 2005). Saunas, in particular, have been associated with cardiovascular benefits when used appropriately (Laukkanen et al., 2015).

However, individuals with cardiovascular conditions should seek medical advice before prolonged exposure to heat-based therapies.

5.0 Beauty Services and Psychological Well-Being

Spas often provide beauty services such as manicures, pedicures and grooming treatments. While primarily aesthetic, such services can enhance self-esteem and body image, which are closely linked to psychological wellbeing (Cash and Smolak, 2011).

Engaging in self-care rituals may also foster a sense of control and personal investment in health.

6.0 Holistic and Complementary Therapies

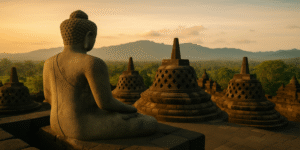

Many spas incorporate holistic therapies aimed at addressing the mind–body connection. These may include:

- Yoga and meditation

- Acupuncture

- Reiki and energy-based therapies

Yoga and meditation are supported by substantial evidence demonstrating reductions in stress, anxiety and blood pressure (Streeter et al., 2012; Goyal et al., 2014). Acupuncture has been recognised by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2021) as beneficial for certain chronic pain conditions.

Holistic approaches emphasise balance, relaxation and integrated wellbeing.

7.0 Healthy Living and Wellness Programmes

Modern spas increasingly offer structured wellness programmes incorporating:

- Nutritional guidance

- Fitness coaching

- Stress management workshops

- Mindfulness training

Lifestyle medicine research indicates that combined interventions addressing diet, physical activity and stress management significantly reduce chronic disease risk (Ornish, 2008).

For example, a week-long wellness retreat may include guided exercise, educational seminars and mindfulness sessions, empowering individuals to adopt sustainable healthy habits.

Psychological Benefits of Spa Experiences

Beyond physical interventions, spa environments provide a psychological sanctuary. Exposure to calming environments reduces sympathetic nervous system activity and promotes parasympathetic activation (Ulrich et al., 1991).

The ambience—soft lighting, soothing music and tranquil décor—supports relaxation and mental decompression. Even brief spa visits may reduce perceived stress and enhance mood.

The Spa as Preventive Healthcare

Increasingly, spas are viewed not merely as leisure facilities but as components of preventive healthcare. Chronic stress contributes to cardiovascular disease, immune dysfunction and mental health disorders (McEwen, 2007). Interventions that reduce stress may therefore contribute indirectly to long-term health.

While spa treatments should not replace medical care, they can complement broader health strategies when integrated responsibly.

Limitations and Considerations

It is important to recognise that some spa claims lack strong scientific validation. Consumers should seek qualified practitioners and evidence-based services. Additionally, individuals with medical conditions should consult healthcare professionals before engaging in heat-based or intensive treatments.

Spas represent a multifaceted approach to promoting health, relaxation and well-being. Through massage therapy, hydrotherapy, skincare treatments, holistic practices and structured wellness programmes, spas offer opportunities for physical rejuvenation and psychological restoration.

Although not a substitute for clinical care, spa services can serve as valuable adjuncts to healthy lifestyles. By providing structured environments dedicated to rest and renewal, spas contribute meaningfully to stress management and overall quality of life.

References

Baumann, L. (2015) Cosmetic Dermatology. 2nd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Becker, B.E. (2009) ‘Aquatic therapy: scientific foundations and clinical rehabilitation applications’, PM&R, 1(9), pp. 859–872.

Bender, T. et al. (2005) ‘Hydrotherapy, balneotherapy and spa treatment’, Rheumatology International, 25(3), pp. 220–224.

British Association of Dermatologists (2022) Skin care and treatments. Available at: https://www.bad.org.uk.

Cash, T.F. and Smolak, L. (2011) Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press.

Cohen, M. and Bodeker, G. (2008) Understanding the Global Spa Industry. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Draelos, Z.D. (2012) Cosmetic Dermatology: Products and Procedures. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Field, T. (2016) ‘Massage therapy research review’, Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 24, pp. 19–31.

Goyal, M. et al. (2014) ‘Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being’, JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), pp. 357–368.

International Spa Association (2023) What is a spa? Available at: https://www.experienceispa.com.

Laukkanen, T. et al. (2015) ‘Association between sauna bathing and cardiovascular health’, JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(4), pp. 542–548.

McEwen, B.S. (2007) ‘Physiology and neurobiology of stress’, Physiological Reviews, 87(3), pp. 873–904.

Moyer, C.A., Rounds, J. and Hannum, J.W. (2004) ‘A meta-analysis of massage therapy research’, Psychological Bulletin, 130(1), pp. 3–18.

Nasermoaddeli, A. and Kagamimori, S. (2005) ‘Balneotherapy in medicine’, Japanese Journal of Health Sciences, 4(3), pp. 181–186.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021) Chronic pain management guidance. London: NICE.

Ornish, D. (2008) The Spectrum. New York: Ballantine Books.

Streeter, C.C. et al. (2012) ‘Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system’, Medical Hypotheses, 78(5), pp. 571–579.

Ulrich, R.S. et al. (1991) ‘Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments’, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11(3), pp. 201–230.