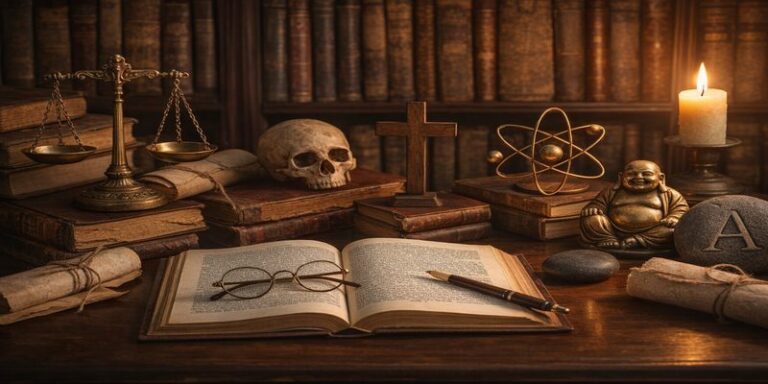

Across philosophical history, the question “What is the meaning of life?” has been addressed through diverse ideological frameworks including Realism, Idealism, Nihilism, Humanism, Stoicism, Materialism, Christianity, Buddhism, Hedonism, and Existentialism. Scholarly literature reveals that these traditions differ primarily in their assumptions about reality (metaphysics), knowledge (epistemology), value (axiology), and human nature (Masih, 1999; Loiko, 2020). Contemporary interdisciplinary research also integrates psychological perspectives on meaning, suggesting that philosophical traditions continue to shape modern well-being theory and practice (Vos, 2018; Fletcher, 2016).

Collectively, academic discussions indicate three broad approaches:

- Objective meaning grounded in metaphysical or theological reality.

- Subjective meaning created by individuals.

- Sceptical or nihilistic rejection of inherent meaning.

The following sections examine each ideology with reference to textbooks, peer-reviewed studies and reputable philosophical scholarship.

1.0 Realism: Meaning as Objective Truth

Philosophical Realism holds that reality exists independently of human perception. Meaning, therefore, is discovered rather than invented. Classical realism, rooted in Aristotle and later developed in scholastic philosophy, maintains that truth corresponds to objective states of affairs (Masih, 1999).

In practical terms, a realist may argue that moral truths—such as justice or human dignity—exist regardless of individual opinion. For example, contemporary ethical discussions in the Encyclopedia of Ethics emphasise realism in moral philosophy, arguing that ethical norms are not merely subjective preferences (Becker & Becker, 2013).

Thus, within realism, the meaning of life is tied to aligning oneself with objective moral and metaphysical order.

2.0 Idealism: Reality as Mind-Dependent

In contrast, Idealism asserts that reality is fundamentally mental or spiritual. From Plato to Kant and German Idealists, meaning arises from the structures of consciousness (Masih, 1999).

Idealists contend that human beings construct meaning through rational reflection. As Andrews (2010) explains, idealism emphasises ideas over material substance, influencing both metaphysical and ethical thought.

For example, an idealist teacher might argue that education’s purpose is not economic productivity but the cultivation of rational and moral consciousness. Meaning, therefore, emerges through intellectual and spiritual development.

3.0 Materialism: Matter as Ultimate Reality

Materialism rejects spiritual or immaterial explanations, asserting that only physical matter exists. Modern scientific naturalism often reflects this stance (Loiko, 2020).

Materialists may interpret meaning biologically or socially rather than metaphysically. For example, evolutionary accounts explain moral behaviour in terms of survival advantage. Dilworth (2022) notes that contemporary debates between materialism and transcendental naturalism shape modern interpretations of value and purpose.

Under strict materialism, meaning is not transcendent but arises from human projects within a physical universe.

4.0 Nihilism: The Denial of Inherent Meaning

Nihilism argues that life lacks intrinsic meaning or value. Associated with Nietzsche and later existential thought, nihilism challenges religious and metaphysical foundations (Aho, 2014).

In contemporary scholarship, nihilism is often discussed in relation to existential crises and moral relativism (Dowdall, 2021). For instance, if moral values are socially constructed, then they lack objective grounding.

However, some philosophers distinguish between passive nihilism (despair) and active nihilism, which creates new values. Thus, nihilism may serve as a transitional critique rather than a final position.

5.0 Humanism: Meaning Through Human Flourishing

Humanism centres meaning on human dignity, rationality and ethical responsibility without reliance on supernatural authority. Herrick (2010) describes modern humanism as affirming moral responsibility grounded in human welfare rather than divine command.

Humanistic perspectives emphasise education, democratic values and compassion. In applied contexts, humanistic psychology encourages individuals to pursue self-actualisation and authentic relationships.

For example, secular charities motivated by humanist ethics prioritise human welfare as an intrinsic good. Meaning arises from contributing to human flourishing.

6.0 Stoicism: Virtue as the Highest Good

Stoicism, founded in ancient Greece, teaches that meaning derives from living in accordance with reason and virtue. External circumstances—wealth, health, status—are considered indifferent compared to moral character (Fletcher, 2016).

Modern applications of Stoicism in psychotherapy demonstrate its enduring relevance (Dryden & Still, 2018). Stoic practices such as negative visualisation cultivate resilience.

For example, an employee facing redundancy might apply Stoic principles by distinguishing between what is within their control (effort, attitude) and what is not (corporate decisions). Meaning lies in moral integrity rather than external success.

7.0 Hedonism: Pleasure as the Ultimate Value

Hedonism defines the good life in terms of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. Classical Epicureanism advocated moderate, rational pleasure rather than indulgence (Masih, 1999).

In contemporary philosophy of well-being, hedonism remains influential (Fletcher, 2016). However, critics argue that pleasure alone cannot account for moral depth or long-term fulfilment.

For instance, excessive consumption may yield temporary pleasure but undermine well-being. Thus, refined hedonism distinguishes between higher and lower pleasures.

8.0 Christianity: Meaning Rooted in Divine Purpose

Within Christian philosophy, meaning is grounded in relationship with God. Human life is understood as purposeful within divine creation (McPherson, 2017).

Christian theology asserts that moral obligations derive from God’s will. Stoic ideas influenced early Christian moral thought, particularly regarding virtue and endurance (Dryden & Still, 2018).

For example, acts of charity are interpreted not merely as social duties but as expressions of divine love. Meaning is therefore theocentric rather than anthropocentric.

9.0 Buddhism: Liberation from Suffering

Buddhist philosophy locates life’s central problem in suffering (dukkha), caused by desire and attachment. The meaning of life lies in achieving liberation through the Noble Eightfold Path (McPherson, 2017).

Unlike theistic traditions, Buddhism does not ground meaning in a creator deity but in spiritual awakening.

For example, mindfulness practices in contemporary psychology derive from Buddhist principles of detachment and compassion. Meaning emerges from freedom from craving and cultivation of wisdom.

10.0 Existentialism and Subjectivism: Creating Meaning

Closely related to nihilism but more constructive, Existentialism argues that meaning is not given but created through authentic choice (Aho, 2014).

Jean-Paul Sartre famously declared that “existence precedes essence,” implying that individuals define themselves through action. This position resonates with contemporary therapeutic approaches emphasising responsibility and self-definition (Vos, 2018).

For instance, a career change motivated by personal values rather than social expectation exemplifies existential authenticity. Meaning arises from self-commitment and freedom.

Comparative Reflection

The examined ideologies reveal that the meaning of life can be interpreted as:

- Objective alignment with reality (Realism)

- Mental or spiritual construction (Idealism)

- Human-centred flourishing (Humanism)

- Virtuous resilience (Stoicism)

- Pleasure optimisation (Hedonism)

- Divine purpose (Christianity)

- Liberation from suffering (Buddhism)

- Self-created authenticity (Existentialism)

- Or the denial of meaning (Nihilism)

Contemporary interdisciplinary research suggests that individuals often combine elements from multiple traditions (Vos, 2018). For example, a secular professional might adopt Stoic resilience, humanist ethics and existential self-creation simultaneously.

The philosophical quest for meaning remains central to both classical metaphysics and modern psychological inquiry. While no single ideology provides universal consensus, each offers a coherent framework shaped by its metaphysical and ethical assumptions.

Ultimately, the enduring significance of these traditions lies not merely in theoretical speculation but in their practical guidance for living. Whether one grounds meaning in objective truth, divine command, human flourishing, rational virtue, spiritual awakening or personal freedom, the debate itself underscores philosophy’s essential role in shaping human self-understanding.

References

Aho, K. (2014) Existentialism: An Introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Andrews, J. (2010) The Economist Book of Isms. London: Profile Books.

Becker, L.C. and Becker, C.B. (2013) Encyclopedia of Ethics. 2nd edn. New York: Routledge.

Dilworth, D.A. (2022) ‘Transcendental naturalism and skeptical materialism’, Cognitio: Revista de Filosofia, 23(2), pp. 1–18.

Dowdall, T. (2021) The Relationship Between Max Stirner’s Thought and Nihilism. PhD thesis. University of Birmingham.

Dryden, W. and Still, A. (2018) The Historical and Philosophical Context of Rational Psychotherapy. London: Routledge.

Fletcher, G. (2016) The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Well-Being. London: Routledge.

Herrick, J. (2010) Humanism: An Introduction. London: Bloomsbury.

Loiko, A.I. (2020) Electronic Textbook for the Educational Discipline “Philosophy”. Minsk: BNTU.

Masih, Y. (1999) A Critical History of Western Philosophy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

McPherson, D. (2017) Spirituality and the Good Life: Philosophical Approaches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vos, J. (2018) Meaning in Life: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Practitioners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.