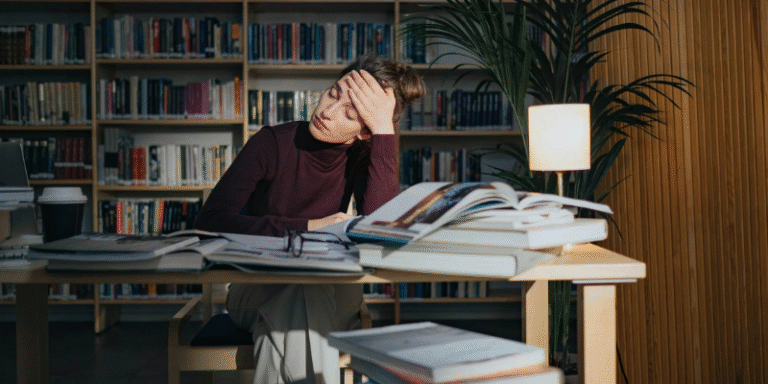

In today’s fast-paced and performance-driven society, burnout syndrome has emerged as a significant occupational and public health concern. Characterised by chronic psychological stress, emotional exhaustion, and reduced effectiveness, burnout affects professionals, caregivers, students, parents, and volunteers alike. While often associated with demanding workplaces, burnout reflects a broader imbalance between sustained stress and insufficient recovery. Increasingly, researchers and health organisations recognise burnout as a serious threat to both individual wellbeing and organisational sustainability.

This article explores the definition, symptoms, causes, risk factors, and prevention strategies associated with burnout, drawing upon textbooks, peer-reviewed research and reputable health authorities using the Harvard referencing system and British spelling.

1.0 What is Burnout?

The concept of burnout was first introduced by Herbert Freudenberger (1982), who described it as a state of mental and physical exhaustion resulting from excessive workplace demands. Over time, the construct was refined by Christina Maslach and colleagues, who conceptualised burnout as a multidimensional syndrome involving three core components (Maslach and Leiter, 2016):

- Emotional exhaustion – feeling drained and depleted of emotional resources

- Depersonalisation (cynicism) – developing a detached or negative attitude towards work or recipients of care

- Reduced personal accomplishment – perceiving diminished competence and achievement

The World Health Organization (2019) now classifies burnout as an “occupational phenomenon” in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), defining it as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. Importantly, burnout is not classified as a medical condition but is recognised as a significant occupational risk factor.

2.0 The Progressive Cycle of Burnout

Burnout develops gradually rather than suddenly. Freudenberger (1982) described it as a process of progressive disillusionment, where enthusiasm slowly transforms into exhaustion and withdrawal.

Contemporary models outline a cycle that typically unfolds in stages:

- Overcommitment – excessive drive to prove oneself, often accompanied by perfectionism

- Neglect of personal needs – reduced self-care, sleep deprivation, and overworking

- Frustration and conflict – increasing irritability and declining satisfaction

- Apathy and detachment – emotional numbness and withdrawal

- Chronic distress or depression-like symptoms

This progression highlights that burnout is not a single event but a gradual erosion of resilience under sustained stress.

3.0 Signs and Symptoms of Burnout

Burnout manifests across physical, emotional, cognitive, behavioural, and interpersonal domains.

3.1 Physical Symptoms

Common physical manifestations include:

- Chronic fatigue

- Headaches and muscle tension

- Gastrointestinal disturbances

- Sleep disturbances (insomnia or hypersomnia)

- Appetite changes

Shirom (2005) suggests that prolonged stress may dysregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, contributing to persistent physiological exhaustion.

For example, healthcare workers experiencing prolonged stress may report frequent colds or persistent tension headaches.

3.2 Emotional Symptoms

Emotional changes often precede physical decline. These include:

- Feelings of helplessness or hopelessness

- Irritability and frustration

- Emotional detachment

- Loss of motivation

Burnout shares similarities with depression; however, burnout is specifically tied to occupational stress (Bianchi, Schonfeld and Laurent, 2015). Emotional exhaustion is often the earliest warning sign.

3.3 Cognitive Symptoms

Cognitive functioning may also deteriorate, resulting in:

- Difficulty concentrating

- Memory lapses

- Impaired decision-making

- Reduced creativity

Bianchi et al. (2015) highlight overlap between burnout and depressive cognitive symptoms, particularly in executive functioning deficits.

3.4 Behavioural Symptoms

Behavioural changes may include:

- Increased absenteeism

- Procrastination

- Reduced productivity

- Reliance on maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., overeating, substance use)

Such behaviours can create a feedback loop, worsening stress and performance concerns.

3.5 Interpersonal Symptoms

Burnout can strain relationships through:

- Cynicism towards colleagues or clients

- Social withdrawal

- Reduced empathy

For example, teachers experiencing burnout may become emotionally detached from students, reducing job satisfaction and classroom effectiveness.

4.0 Causes and Risk Factors

Burnout arises from a complex interaction of organisational and personal factors. Maslach and Leiter (2016) identify six key areas of mismatch between individuals and their work environment:

- Workload – excessive demands without adequate recovery

- Control – limited autonomy or decision-making power

- Reward – insufficient recognition or compensation

- Community – poor workplace relationships or social isolation

- Fairness – perceived inequality or injustice

- Values conflict – misalignment between personal and organisational ethics

High-risk groups include:

- Healthcare professionals

- Teachers

- Social workers

- Emergency responders

- Students and entrepreneurs

For example, junior doctors working long shifts with limited control over schedules are particularly vulnerable.

5.0 The Psychological and Biological Mechanisms

Burnout reflects prolonged activation of the stress response system. Chronic exposure to stress hormones such as cortisol may impair immune function, sleep regulation and emotional control (Shirom, 2005).

From a psychological perspective, burnout involves learned helplessness and diminished self-efficacy, where individuals feel unable to influence outcomes despite continued effort (Maslach and Leiter, 2016).

6.0 Prevention and Management Strategies

Addressing burnout requires interventions at individual, organisational, and systemic levels.

6.1 Individual Strategies

- Prioritising sleep, nutrition and physical activity

- Practising mindfulness and relaxation techniques

- Setting clear boundaries around work hours

- Seeking psychological support when needed

A meta-analysis by Grossman et al. (2004) demonstrated that mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) significantly improves stress and wellbeing.

For example, dedicating 10–15 minutes daily to breathing exercises may reduce physiological arousal.

6.2 Organisational Interventions

Workplace strategies include:

- Promoting realistic workloads

- Providing flexible scheduling

- Encouraging open communication

- Supporting employee wellbeing programmes

Leadership style also plays a critical role. Goleman (1996) emphasised the importance of emotional intelligence in fostering supportive work environments.

6.3 Systemic Solutions

Broader strategies involve:

- Policy reforms limiting excessive overtime

- Encouraging mental health days

- Reducing stigma around stress

- Embedding emotional regulation education into schools

The WHO (2019) highlights the importance of organisational responsibility in preventing burnout.

7.0 Burnout vs Depression: Clarifying the Distinction

Although burnout and depression overlap symptomatically, burnout is primarily work-related, whereas depression affects multiple life domains (Bianchi et al., 2015). However, untreated burnout may evolve into clinical depression, making early intervention essential.

Burnout syndrome is more than temporary tiredness—it is a multidimensional stress-related condition with significant physical, emotional and organisational consequences. Rooted in chronic, unmanaged stress, burnout unfolds gradually, undermining motivation, health and interpersonal relationships.

Prevention requires a holistic approach, combining personal resilience strategies with organisational reform and societal awareness. By recognising early warning signs and implementing structured interventions, individuals and institutions can reduce the impact of this modern epidemic.

Investing in mental wellbeing is not merely a moral responsibility—it is essential for sustainable performance, productivity and human flourishing.

References

Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I.S. and Laurent, E. (2015) ‘Burnout-depression overlap: A review’, Clinical Psychology Review, 36, pp. 28–41.

Freudenberger, H.J. (1982) Burn-Out: The High Cost of High Achievement. New York: Doubleday.

Goleman, D. (1996) Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. London: Bloomsbury.

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S. and Walach, H. (2004) ‘Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis’, Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), pp. 35–43.

Maslach, C. and Leiter, M.P. (2016) ‘Burnout’, in Cooper, C.L. and Quick, J.C. (eds.) The Handbook of Stress and Health. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 103–120.

Shirom, A. (2005) ‘Reflections on the study of burnout’, Work & Stress, 19(3), pp. 263–270.

World Health Organization (2019) ‘Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”’, Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019 (Accessed: 3 June 2025).