Using Artificial Intelligence for Job Applications and Interview Preparation: A Practical Guide

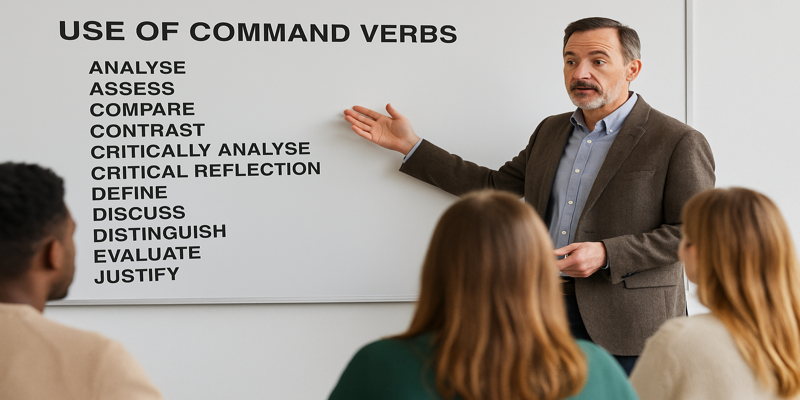

The rapid advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has revolutionised recruitment processes, fundamentally altering how job seekers prepare applications and interviews. AI tools have evolved beyond basic grammar checks to offer data-driven insights, automated keyword analysis, and simulated interview experiences, supporting candidates in developing well-structured, tailored, and compelling applications. This essay explores the benefits, limitations, and best practices for integrating AI into job application and interview preparation, while maintaining authenticity, accuracy, and personal voice. 1.0 Benefits of Using AI in Job Applications AI provides a wide array of advantages to job seekers, particularly in enhancing the efficiency, accuracy, and relevance of applications. According to Gupta (2025), AI platforms can analyse large datasets of job descriptions, identifying the key competencies and keywords that employers seek (Journal of Computer Science and Technology Studies, 4(1), pp. 45–59). This ensures that CVs and cover letters are optimised for Applicant Tracking Systems (ATS), which automatically screen candidates before human review. Furthermore, AI tools such as ChatGPT, Grammarly, and Jobscan can suggest appropriate phrases, improve tone and readability, and align language with industry expectations (Kim & Heo, 2022, Information Technology & People, 35(2), pp. 307–324). Such tools can also provide structural templates for CVs and cover letters, helping candidates overcome the “blank page” barrier. Research by Jaser et al. (2021) in the University of Sussex AI Toolkit found that AI tools enhance confidence and efficiency in job preparation, particularly for early-career professionals who struggle with professional writing conventions. Similarly, Nithya (2023) in Intelligent Job Interview Preparation and Career Advancement noted that AI-driven job matching systems improve alignment between applicants’ skills and employer requirements by analysing historical hiring data and success rates. Example: A marketing graduate might use Jobscan to analyse a job posting for a “Marketing Communications Officer” role. The AI identifies key terms such as “SEO”, “campaign management”, and “stakeholder engagement”. By integrating these into the CV, the applicant enhances their visibility in ATS systems — an increasingly critical step, as over 75% of employers in the UK use such software (CIPD, 2024). 2.0 Limitations and Ethical Considerations Despite its advantages, AI should not be relied upon to produce job applications from start to finish. AI lacks contextual understanding of individual personalities, authentic motivations, and unique experiences (Jones et al., 2020, Educause Review). Overreliance on AI risks generating generic, formulaic, and even inaccurate documents. Research by Canagasuriam and Lukacik (2025, International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 33(1), pp. 99–115) highlights a growing trend of “AI plagiarism,” where identical AI-generated cover letters are detected across applications. Recruiters can easily identify such content due to repeated phrasing and structure. AI tools may also generate incorrect or misleading information, particularly when prompted with vague instructions. For example, in a study on AI-based CV generation, Jarvis et al. (2024, RELC Journal, 55(2), pp. 212–230) found that nearly 40% of AI-produced CVs contained factual inconsistencies or unrealistic skills. Additionally, linguistic accuracy is essential: candidates applying for UK roles should ensure the use of British spelling conventions (e.g., organisation instead of organization). AI systems often default to American English unless specifically instructed otherwise. Finally, AI-generated CVs often produce uniform designs and predictable layouts, diminishing uniqueness. As Fulk et al. (2022, Issues in Information Systems, 23(3), pp. 88–103) suggest, “AI should act as a scaffold for human creativity, not a substitute for it.” 3.0 The Blended Approach: Combining AI with Human Insight The most effective strategy is a blended approach — combining AI capabilities with human judgment, reflection, and customisation. This process can be divided into four main steps: Step 1: Preparation (No AI Use) Applicants should begin with independent research on the role, organisation, and industry. As Lewton and Haddad (2024, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 88(2), pp. 55–67) assert, understanding the company’s values, mission, and goals helps tailor applications authentically. Creating a spreadsheet to track applications—including submission dates, job titles, and outcomes—helps identify patterns in successful submissions. This mirrors effective research methods in project management and job search strategies (CIPD, 2024). Step 2: Prompting (AI Use Begins) Using precise prompts enhances AI output. For example: “I am a marketing professional applying for a Director of Marketing and Communications role. Based on the job description below, write a cover letter that highlights my leadership, strategic communication, and digital campaign experience.” Such context-rich prompts yield better results than generic commands. AI tools like Zety and ChatGPT can refine wording and highlight transferable skills while ensuring keyword optimisation for ATS systems (Kim & Heo, 2022). Step 3: Review and Customisation Once AI has produced a draft, the applicant must critically review and personalise it. This involves aligning the language with one’s authentic voice, verifying factual details, and matching examples with actual achievements. As highlighted by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD, 2024), this step transforms AI-assisted text into a genuine representation of the candidate’s capabilities. Step 4: AI for Interview Preparation AI-powered mock interview platforms such as AIApply, Google Interview Warmup, Huru, and Big Interview use natural language processing (NLP) to simulate real interview environments (Yalla et al., 2025, IEEE 8th International Conference on AI Systems). These systems provide feedback on tone, pacing, and content relevance. A study by Pertiwi and Kusumaningrum (2021) found that students using AI-based mock interviews demonstrated a 35% improvement in confidence and articulation compared to traditional preparation methods. AI’s ability to analyse speech and body language offers users immediate, actionable insights (Lee & Kim, 2021, International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology). 4.0 Best Practices for Ethical and Effective AI Use To ensure that AI enhances rather than undermines your job application: Stay Authentic: Always review and personalise AI-generated text to reflect genuine experiences and values. Ensure Accuracy: Double-check all facts, achievements, and employment dates. Use British English: Set spelling preferences before generation. Avoid Overreliance: Use AI as an assistant, not as a replacement. Maintain Privacy: Avoid inputting confidential personal or company data into AI systems. Leverage Feedback Loops: Use AI-generated insights to refine your tone, structure, and storytelling. As Kammerer (2021, Iowa Law … Read more