Calculus: The Study of How Things Change

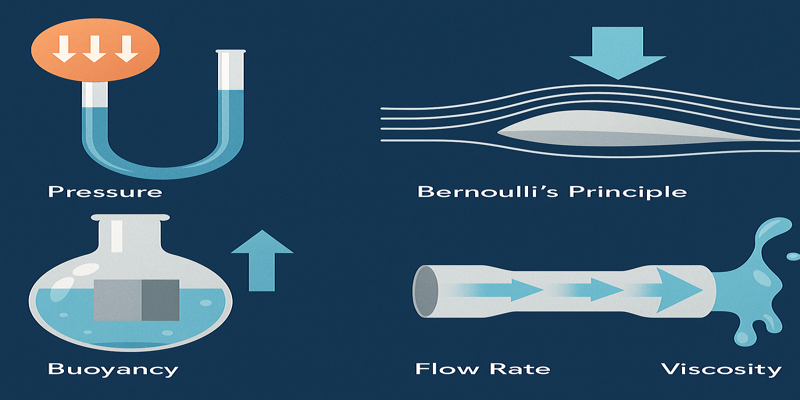

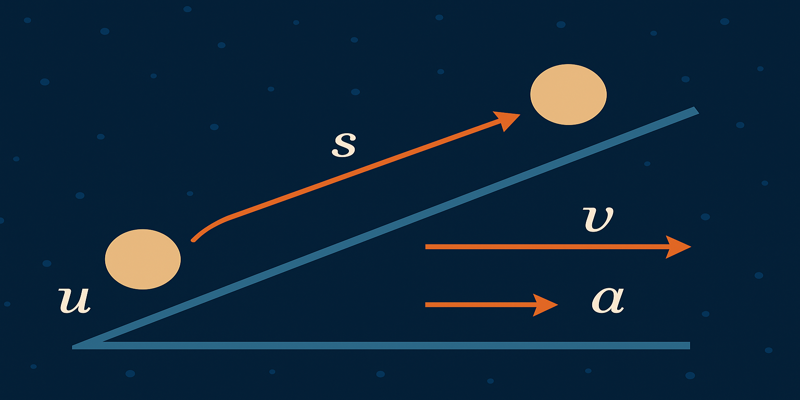

Calculus and Real Analysis lie at the heart of undergraduate mathematics education. These two domains, though often perceived as abstract or technical, underpin the entire structure of modern science and technology. Calculus, first formalised in the 17th century by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, provides a systematic method for analysing change, motion, and accumulation. On the other hand, Real Analysis takes the intuitive tools of calculus and investigates them through a rigorous, formal framework. Together, they form the twin pillars of mathematical understanding, from engineering to economics. The Essence of Calculus At its core, calculus is the study of how things change. The discipline is traditionally divided into two major branches: differential calculus, which concerns itself with rates of change (slopes and tangents), and integral calculus, which deals with accumulation (areas under curves and total quantities). Differentiation gives us a way to model instantaneous change. For example, the velocity of a moving car is the derivative of its position function over time. Similarly, integration is used to determine the area under a curve, the distance travelled over time, or the total accumulated growth of an investment (Stewart, 2015). The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus links these two branches, showing that differentiation and integration are essentially inverse operations (Apostol, 1967). Calculus is not just a mathematical curiosity; it is the backbone of physics, engineering, and even social sciences. For instance, in economics, calculus is used to find maximum profit or minimum cost functions by identifying turning points on curves (Chiang & Wainwright, 2005). In biology, it helps model the rate of change in populations. In medicine, it assists in the analysis of rates of drug absorption. Transitioning to Abstraction: The Need for Real Analysis While calculus equips students with powerful tools for computation and application, it often lacks rigorous foundations. Real Analysis, sometimes simply called “analysis”, addresses this gap. It formalises the underlying principles of calculus by investigating limits, continuity, convergence, and differentiability using precise definitions and logical deduction. As Houston (2001) aptly describes, “analysis teaches students to move from computational skills to abstract mathematical reasoning” (p. 42). This transition is critical for those intending to pursue higher mathematics, where proofs, logic, and rigour dominate over computation. One of the most crucial aspects of real analysis is the concept of limits. Though introduced in introductory calculus, limits are often treated heuristically. In analysis, they are given a formal definition using ε (epsilon) and δ (delta) notation, which demands precise understanding. This leads to a more refined approach to topics such as continuity and uniform convergence, which are essential for ensuring the stability and reliability of mathematical models (Bartle & Sherbert, 2011). Sequences, Series, and Convergence Another central component of real analysis is the study of sequences and series. These concepts allow mathematicians to examine infinite processes in a controlled manner. For example, the infinite series ∑n=1∞1n2\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n^2}n=1∑∞n21 converges to a finite number, a fact discovered in the 18th century and proven by Euler. Understanding why and how such series converge lies in the realm of real analysis. Such knowledge is essential when dealing with Fourier Series, Taylor Series, and other approximations used in signal processing, quantum mechanics, and numerical analysis. The convergence of series is not merely a mathematical curiosity; it has practical implications in the design of everything from sound systems to MRI scanners (Rudin, 1976). Continuity and Differentiability: More Than Smooth Curves In calculus, a function is typically assumed to be continuous and differentiable. However, analysis challenges us to define and test these properties rigorously. For instance, the function f(x)={x2sin(1x),x≠00,x=0f(x) = \begin{cases} x^2 \sin \left( \frac{1}{x} \right), & x \neq 0 \\ 0, & x = 0 \end{cases} f(x)={x2sin(x1),0,x=0x=0 is continuous at zero, but not differentiable there. Real analysis teaches us to detect and understand such subtleties. These nuances are vital in applied mathematics. In physical systems, continuity and differentiability often correspond to real-world smoothness — whether it’s airflow over a wing or voltage in an electrical circuit. Rigorous definitions ensure our models reflect physical reality faithfully and do not produce unexpected or nonsensical results (Abbott, 2015). Bridging the Theoretical and Practical Although real analysis might seem abstract, its impact on numerical methods is profound. Techniques such as Newton-Raphson iteration, finite difference methods, and error analysis rely on a deep understanding of function behaviour and convergence — all topics rooted in real analysis (Burden & Faires, 2011). In computer science, too, analysis plays a crucial role. Algorithms for data compression, image recognition, and machine learning involve optimisation techniques grounded in calculus and extended by analysis. Even Google’s PageRank algorithm uses iterative methods inspired by calculus to rank web pages (Langville & Meyer, 2006). Pedagogical Importance and Cognitive Growth The study of calculus followed by real analysis is more than just learning new mathematical tools; it represents a cognitive shift. As students grapple with formal definitions and theorems, they develop logical thinking, problem decomposition, and proof-writing skills. These are not only mathematical tools but essential components of analytical thinking applicable in any field. Houston (2001) argues that this transition is one of the most intellectually demanding but rewarding experiences for mathematics students. It mirrors the evolution of mathematical thought itself — from the heuristic to the rigorous, from the intuitive to the deductive. From the tangible calculations of instantaneous speed to the abstract ideas of convergence and continuity, calculus and real analysis together form the foundation of modern mathematics. They are indispensable tools for scientists, engineers, economists, and computer scientists. More importantly, they reflect the human pursuit of understanding change, structure, and logic in the most precise way possible. The progression from calculus to real analysis is more than academic; it is an intellectual rite of passage. It challenges the mind, refines intuition, and lays the groundwork for all further mathematical exploration. For anyone stepping into the world of mathematics, there can be no deeper or more rewarding journey. References Abbott, S. (2015). Understanding Analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. Apostol, T. M. (1967). Calculus, Volume I (2nd ed.). … Read more