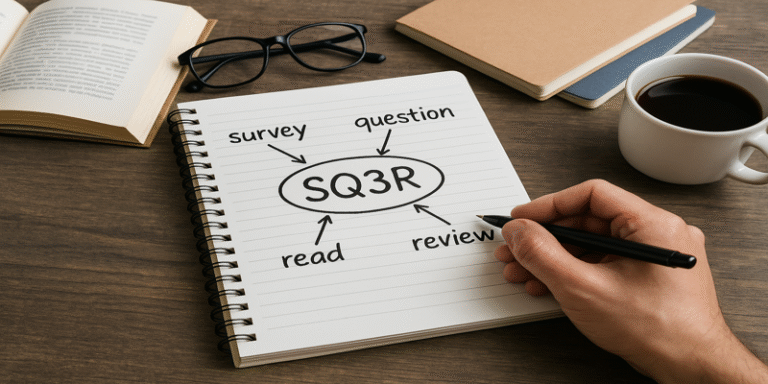

Survey, Question, Read, Recall and Review (SQ3R): An Effective Reading Strategy

Effective reading and study strategies are fundamental to academic success. One of the most influential methods is the SQ3R system, an acronym for Survey, Question, Read, Recall, and Review. Developed by Francis P. Robinson (1946) in his book Effective Study, the system provides a structured approach to reading comprehension and retention. Its effectiveness lies in transforming passive reading into an active learning process (Cottrell, 2019). This article critically discusses the SQ3R system, explores its application in different learning contexts, and analyses its relevance in the digital learning environment.

Origins and Importance of SQ3R

The SQ3R method was designed during the Second World War to help army personnel study efficiently (Robinson, 1946). Since then, it has become a staple in study skills programmes worldwide, emphasising critical thinking and information retention. According to Weinstein and Mayer (1986), learning strategies such as SQ3R enhance cognitive engagement and enable learners to construct meaningful connections between new knowledge and prior understanding.

In an era of information overload, SQ3R offers a systematic framework for processing large amounts of material, particularly useful in higher education where students must engage with complex academic texts (Nist & Simpson, 2000).

Step 1: Survey

The first stage, Survey, involves scanning the material to gain an overview. This includes reading titles, subheadings, introductions, summaries, and visual aids (SQ3R document; Cottrell, 2019). The purpose is to establish a mental map of the text’s structure, enabling learners to set goals and expectations.

For example, when approaching a chapter in a psychology textbook, a student may skim the headings on cognitive development and glance at figures or diagrams. This primes the mind to expect information about stages of development, key theorists, and empirical studies. Research by Rayner et al. (2012) demonstrates that previewing texts increases comprehension by providing a framework for active reading.

Step 2: Question

In the Question stage, learners transform headings and subheadings into questions. This step encourages active engagement with the material. Instead of passively reading, the student anticipates answers, fostering curiosity and deeper understanding (Nist & Holschuh, 2012).

For instance, a heading such as “Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development” may lead to questions such as: What are Piaget’s stages? or How do they explain child learning?. This aligns with constructivist learning theory, which suggests that learning occurs when individuals actively construct knowledge (Bruner, 1961).

Step 3: Read

The Read stage involves carefully engaging with the text to answer the formulated questions. Reading becomes purposeful and focused, reducing distractions and improving retention.

Empirical studies support this approach. McNamara (2009) found that students using structured reading strategies like SQ3R demonstrated improved comprehension, particularly when dealing with challenging texts. By continuously checking whether their questions are answered, learners also develop critical literacy skills, essential in academic research.

Step 4: Recall

Once a section is read, the Recall stage requires learners to summarise the main points from memory. This reinforces active retrieval, a process that has been shown to strengthen memory consolidation (Roediger & Butler, 2011).

For example, after reading about Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, a student may close the book and attempt to explain the concept in their own words. This mirrors the testing effect, where retrieving knowledge enhances long-term retention (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011).

Step 5: Review

Finally, Review involves revisiting questions, notes, and summaries to ensure understanding is consolidated. This step fosters distributed practice, a highly effective learning strategy (Cepeda et al., 2006). Reviewing not only improves memory but also refines organisational skills, as learners restructure notes and highlight connections across chapters.

As the SQ3R document emphasises, the Review phase ensures that “the information you gain from reading is important” rather than superficial (SQ3R document). In practice, this might mean revisiting a week’s lecture readings before an exam, thereby reinforcing knowledge systematically.

Applications in Academic and Professional Settings

The SQ3R system is widely used in academic contexts, from secondary education to postgraduate research. For instance, medical students often face extensive reading lists; applying SQ3R helps them prioritise key learning outcomes, particularly when studying clinical case studies (Brown et al., 2014).

In professional environments, SQ3R is equally valuable. Business leaders analysing industry reports can apply the method to extract strategic insights efficiently. Similarly, in law, where practitioners must interpret dense legal texts, SQ3R provides a structured approach to identifying relevant arguments and precedents (Cottrell, 2019).

Critiques and Limitations

Despite its strengths, SQ3R is not without criticism. Some researchers argue it is time-consuming, making it less appealing in fast-paced environments (Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995). Additionally, learners with low motivation may struggle to sustain the questioning and recalling processes.

Furthermore, in digital learning environments, where texts are hyperlinked and non-linear, SQ3R may require adaptation. However, studies suggest that combining SQ3R with digital annotation tools enhances its relevance (Mangen et al., 2013).

SQ3R in the Digital Age

The rise of e-learning and digital platforms has changed reading behaviours. Modern students often skim articles online rather than engage in deep reading. Applying SQ3R in digital contexts means using tools such as highlighting software, online flashcards, and summarisation apps to support each stage. For example, surveying may involve scrolling through abstracts and graphical abstracts, while recall may be enhanced using apps like Quizlet.

As Carr (2010) notes in The Shallows, digital reading risks reducing comprehension. Therefore, structured methods like SQ3R are increasingly important in maintaining deep reading practices in an era of distraction.

The SQ3R study system remains one of the most effective strategies for reading comprehension, retention, and academic success. By guiding learners through surveying, questioning, reading, recalling, and reviewing, it transforms passive reading into active learning. While challenges exist, particularly in adapting to digital platforms, the method’s core principles remain relevant.

Ultimately, SQ3R embodies the philosophy that learning requires active effort and reflection. Whether applied by students, professionals, or lifelong learners, it continues to be a cornerstone of effective study skills in the 21st century.

References

Bruner, J. (1961). The Act of Discovery. Harvard University Press.

Brown, C., Roediger, H. & McDaniel, M. (2014). Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning. Harvard University Press.

Carr, N. (2010). The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains. W. W. Norton & Company.

Cepeda, N.J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J.T. & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), pp.354-380.

Cottrell, S. (2019). The Study Skills Handbook. 5th ed. Red Globe Press.

Karpicke, J. & Blunt, J. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying. Science, 331(6018), pp.772-775.

Mangen, A., Walgermo, B. & Brønnick, K. (2013). Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: Effects on reading comprehension. International Journal of Educational Research, 58, pp.61-68.

McNamara, D. (2009). The importance of reading strategies in learning from texts. Cognition and Instruction, 27(3), pp.285-324.

Nist, S.L. & Holschuh, J.P. (2012). Active Learning: Strategies for College Reading. Pearson.

Nist, S.L. & Simpson, M.L. (2000). College studying. In: M.L. Kamil et al. (eds.) Handbook of Reading Research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pressley, M. & Afflerbach, P. (1995). Verbal Protocols of Reading: The Nature of Constructively Responsive Reading. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rayner, K., Foorman, B., Perfetti, C., Pesetsky, D. & Seidenberg, M. (2012). How psychological science informs the teaching of reading. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 2(2), pp.31-74.

Robinson, F.P. (1946). Effective Study. Harper & Row.

Roediger, H. & Butler, A. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), pp.20-27.

Weinstein, C. & Mayer, R. (1986). The teaching of learning strategies. In: M.C. Wittrock (ed.) Handbook of Research on Teaching. Macmillan, pp.315-327.