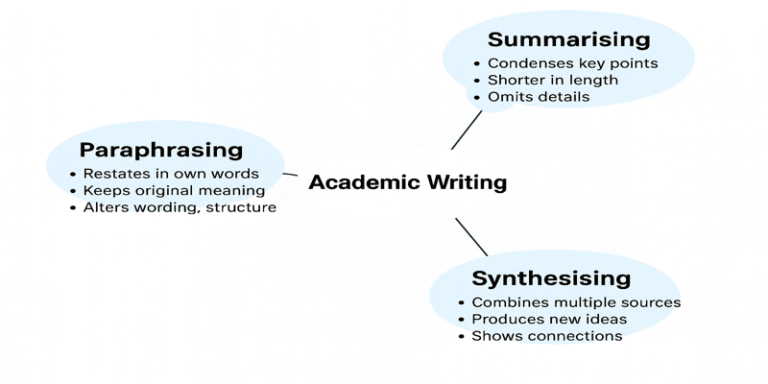

Academic writing requires students and researchers to engage critically with existing literature while producing original work. Three essential techniques that allow this engagement are paraphrasing, summarising, and synthesising. These skills help writers avoid plagiarism, demonstrate understanding, and present coherent arguments by integrating ideas from multiple sources. This article examines the importance of these techniques, outlines strategies for their effective use, and highlights challenges learners face, supported by examples and references to textbooks, journal articles, and reputable academic websites.

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is the process of expressing another author’s ideas in one’s own words without altering the original meaning (Bailey, 2018). Unlike quoting, which reproduces exact words, paraphrasing demonstrates comprehension and allows the writer to integrate information smoothly into their text. For example:

- Original: “MPs were not paid a salary until 1912” (Rush, 2005, p.114).

- Paraphrase: Until the early twentieth century, members of Parliament served without financial remuneration (Rush, 2005).

Effective paraphrasing involves more than simply substituting words with synonyms. It requires restructuring sentences, altering vocabulary, and contextualising ideas. According to Ajmal, Bukhari and Raza (2025), students in higher education often struggle with paraphrasing due to limited exposure to academic conventions. Common pitfalls include patchwriting—copying too closely from the source—or misrepresenting the meaning (Maulidiyah, 2024).

Strategies for effective paraphrasing include:

- Understanding the source fully before rewriting.

- Changing sentence structure rather than word-by-word substitution.

- Using reporting verbs such as “argues,” “suggests,” or “notes.”

- Comparing the paraphrase with the original to check accuracy (University of Manchester, 2020).

Paraphrasing ensures that academic work demonstrates originality while respecting intellectual property.

Summarising

Summarising condenses the main ideas of a source into a shorter version, focusing on key points and omitting detail. It differs from paraphrasing in that it reduces length significantly while retaining essential meaning (Cottrell, 2019). For example:

- Original: “The proportion of manual workers in the parliamentary Labour Party declined from 1945 to 1979, from approximately one in four to one in ten. Of the 412 Labour MPs elected in 2001, 12% were drawn from manual backgrounds” (Criddle cited in Norton, 2005, p.23).

- Summary: The Labour Party’s working-class representation declined significantly from 1945 to 2001 (Norton, 2005).

Summarising is particularly useful when reviewing literature or providing context. Delgado-Osorio (2024) highlights that summarising in academic contexts requires the ability to identify and prioritise relevant ideas, which demands critical thinking. Moreover, Qurbonbayeva (2025) stresses that effective summarisation prevents plagiarism by ensuring writers do not rely excessively on long quotations.

Key techniques include:

- Identifying the thesis or main argument.

- Selecting supporting points relevant to the writer’s purpose.

- Condensing information into concise statements.

- Avoiding unnecessary detail such as examples unless directly relevant.

By summarising effectively, writers can present complex information in a clear, accessible manner while maintaining focus.

Synthesising

Synthesising goes beyond paraphrasing and summarising. It involves combining ideas from multiple sources to produce new insights or arguments (Hart, 2018). Instead of presenting sources separately, synthesis integrates perspectives, showing relationships, agreements, or contradictions. For example:

- Source A: Research shows paraphrasing improves comprehension (Ajmal et al., 2025).

- Source B: Summarising develops the ability to prioritise ideas (Delgado-Osorio, 2024).

- Synthesis: Together, these studies suggest that paraphrasing and summarising complement one another, enhancing both understanding and critical evaluation.

Synthesis is crucial in literature reviews, where the aim is not merely to report what has been written, but to demonstrate how different works contribute to the academic conversation. According to Maulidiyah (2024), synthesis allows writers to construct coherent arguments by linking diverse findings. However, novice writers often list sources sequentially without integrating them, resulting in descriptive rather than analytical writing.

Strategies for synthesis include:

- Comparing and contrasting sources.

- Grouping ideas under themes.

- Highlighting similarities or contradictions.

- Developing new interpretations by combining perspectives.

Synthesis thus represents a higher-order academic skill, requiring both comprehension and critical analysis.

The Role of Paraphrasing, Summarising and Synthesising in Academic Integrity

Proper use of paraphrasing, summarising, and synthesising promotes academic integrity by avoiding plagiarism. Failure to acknowledge sources, whether deliberate or accidental, can result in accusations of academic misconduct (Pears and Shields, 2019). As Qurbonbayeva (2025) notes, these skills not only demonstrate respect for intellectual property but also cultivate a culture of honesty and excellence in writing.

Furthermore, these techniques enhance clarity, ensuring that academic work is accessible to readers. They also show the writer’s ability to critically engage with sources, a key criterion in academic assessment. For example, a literature review on climate change that merely lists sources lacks depth, whereas one that synthesises perspectives demonstrates higher-level critical thinking.

Challenges and Pedagogical Approaches

Students often encounter difficulties in mastering these skills. Ajmal, Bukhari and Raza (2025) observe that language barriers, limited exposure to academic texts, and inadequate training contribute to poor paraphrasing and synthesis. Common errors include over-reliance on quotations, failure to integrate sources, and loss of original meaning.

Pedagogical approaches to address these challenges include:

- Explicit instruction in source-based writing (Maulidiyah, 2024).

- Practice activities focusing on paraphrasing and summarising different types of texts.

- Feedback and peer review, which help students refine their skills.

- Digital tools such as Turnitin, which encourage reflection on originality.

Instructional strategies should focus not only on technical aspects but also on fostering critical thinking.

In conclusion, paraphrasing, summarising, and synthesising are indispensable skills in academic writing. Paraphrasing demonstrates understanding and allows seamless integration of sources. Summarising condenses complex information, enabling clarity and focus. Synthesising integrates multiple perspectives, creating new insights and strengthening arguments. Together, these techniques enhance originality, uphold academic integrity, and promote critical engagement with knowledge. Mastery of these skills requires practice, explicit instruction, and awareness of ethical considerations. For students and researchers, developing competence in these areas is not only a requirement for academic success but also a foundation for lifelong learning.

References

Ajmal, A., Bukhari, S. and Raza, M.A. (2025) ‘Source-based writing skills in higher education: A study of paraphrasing, summarising, and synthesising in Pakistan’s academic context’, International Premier Journal of Languages & Literature, [online]. Available at: https://ipjll.com/ipjll/index.php/journal/article/view/167 (Accessed 11 September 2025).

Bailey, S. (2018) Academic Writing: A Handbook for International Students. 5th ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

Cottrell, S. (2019) The Study Skills Handbook. 5th ed. London: Macmillan.

Delgado-Osorio, X. (2024) ‘Strategic processing of integrated writing tasks in the context of English for academic purposes’, Goethe University Frankfurt Publications, [online]. Available at: https://publikationen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/frontdoor/index/index/docId/87574 (Accessed 11 September 2025).

Hart, C. (2018) Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Research Imagination. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

Maulidiyah, N. (2024) ‘Explicit instruction: A method to engage students in EFL source-based writing’, Journal of English Educational Study, 7(2), pp. 100–112. [online]. Available at: http://jurnal.stkippersada.ac.id/jurnal/index.php/JEES/article/view/4030 (Accessed 11 September 2025).

Norton, P. (2005) Parliament in British Politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pears, R. and Shields, G. (2019) Cite Them Right: The Essential Referencing Guide. 11th ed. London: Red Globe Press.

Qurbonbayeva, O.R. (2025) ‘Strategies for effective summary writing and plagiarism prevention in academic contexts’, Academic Research in Modern Science, [online]. Available at: https://inlibrary.uz/index.php/arims/article/view/69926 (Accessed 11 September 2025).

Rush, M. (2005) Parliament Today. 2nd ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

University of Manchester (2020) Paraphrasing and Summarising Skills. [online]. Available at: https://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/ (Accessed 11 September 2025).