In a world that glorifies grand gestures and instant success, the power of small habits is often underestimated. Saving £8 per day, reading 20 pages per day, or walking 10,000 steps daily—seemingly minor actions accumulate over time to produce significant, life-changing outcomes. The concept of habit formation has been widely studied across psychology, behavioural economics, and neuroscience, demonstrating that small, consistent behaviours can shape one’s health, wealth, and intellectual capacity (Duhigg, 2012; Clear, 2018; Wood & Neal, 2016). This essay explores how incremental daily practices foster long-term transformation, supported by theoretical frameworks and empirical research, and contextualised through real-world examples.

1.0 Theoretical Foundations of Habit Formation

A habit is defined as an automatic behaviour triggered by contextual cues, developed through repetition and reinforcement (Lally et al., 2010). The habit loop—consisting of a cue, routine, and reward—was popularised by Duhigg (2012) in The Power of Habit, describing how consistent engagement in small actions embeds them into neural pathways. Over time, these actions become automatic, reducing cognitive effort and enabling sustained behavioural change.

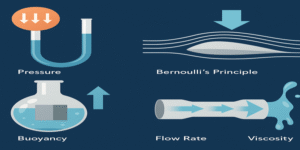

Behavioural psychology underscores the compound effect—the idea that small, repeated actions yield exponential results over time (Hardy, 2010). This principle aligns with cognitive-behavioural theories which assert that consistent reinforcement and self-regulation transform short-term tasks into enduring routines (Bandura, 1991). Furthermore, behavioural economics, through the concept of nudging, supports the notion that small, deliberate adjustments in behaviour can significantly influence long-term outcomes (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).

2.0 Small Financial Habits and the Accumulation of Wealth

The example of saving £8 per day equating to approximately £3,000 per year illustrates the profound effect of consistent small savings. According to the compound interest principle, even modest daily savings grow exponentially over time. Research by Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) highlights that individuals who practise consistent saving habits—regardless of income—accumulate substantially higher lifetime wealth.

Financial behaviour studies show that automaticity and routine in saving foster greater financial stability (Shefrin & Thaler, 1988). Programmes like Save More Tomorrow, designed by Thaler and Benartzi (2004), demonstrate that gradual, habitual increases in savings lead to significant improvements in long-term financial well-being without requiring drastic behavioural shifts. Similarly, in personal finance education, scholars advocate for micro-saving and automated deposits as sustainable strategies to overcome inertia and foster resilience (Fernandes, Lynch & Netemeyer, 2014).

Real-world examples abound. For instance, the “52-week money challenge,” where individuals increase their savings weekly, has gained global popularity as a behavioural tool encouraging consistent saving. This approach mirrors the incremental accumulation demonstrated in the image—showing that modest, repeated actions can build financial security and independence over time.

3.0 Small Intellectual Habits and Cognitive Growth

Reading 20 pages per day, equating to roughly 30 books per year, exemplifies the potential of incremental learning. Research in cognitive psychology demonstrates that frequent reading enhances vocabulary, comprehension, and analytical thinking (Stanovich & Cunningham, 1992). Moreover, consistent reading cultivates metacognition—the ability to think about one’s thinking—enhancing critical and reflective skills essential for lifelong learning (Flavell, 1979).

The small habits principle applies profoundly to learning. According to Ericsson, Krampe, and Tesch-Römer (1993), mastery in any domain arises from deliberate practice—structured, repetitive engagement that gradually improves skill. Reading regularly strengthens cognitive pathways associated with comprehension and retention (Cain & Oakhill, 2006). Over time, such habits compound into significant intellectual growth and professional competence.

Real-world examples reinforce this. Successful individuals, from Warren Buffett to Bill Gates, attribute much of their insight and decision-making ability to their daily reading routines. Buffett reportedly spends 80% of his day reading, while Gates publicly promotes reading 50 books a year as a foundation for personal and professional development (Gelles, 2016). These examples highlight how consistent micro-actions foster intellectual compounding similar to financial investment growth.

4.0 Small Physical Habits and Health Transformation

Walking 10,000 steps daily—approximately five miles—totals nearly 70 marathons annually, demonstrating the cumulative power of consistent physical activity. Empirical evidence underscores the transformative effects of small, regular movements on long-term health outcomes. According to Tudor-Locke and Bassett (2004), achieving 10,000 steps per day significantly reduces cardiovascular risk, obesity, and metabolic syndrome.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, which can easily be achieved through habitual daily walking. Research by Oja et al. (2018) further shows that even incremental increases in step count—such as an additional 1,000 steps per day—reduce all-cause mortality risk by 6–36%. Thus, the consistent act of walking serves as a cornerstone for physical and mental health improvement.

A practical example can be found in Japan’s “walking to work” culture, which promotes active commuting as part of daily life. This small but consistent practice has been linked to Japan’s lower rates of obesity and higher life expectancy compared to many Western nations (Takemi, 2018). Hence, the accumulation of simple habits can yield profound physiological benefits.

5.0 The Neuroscience of Habit and Behavioural Change

Neuroscientific studies reveal that small habits physically reshape the brain. Neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganise itself through repeated experiences—underpins the process of habit formation (Draganski et al., 2004). Repetitive actions strengthen synaptic connections in the basal ganglia, enabling automaticity and freeing up mental resources for higher-order thinking (Graybiel, 2008).

Lally et al. (2010) found that on average, it takes 66 days to form a habit, though the duration varies by complexity. Importantly, missing occasional days does not derail progress, reinforcing the idea that consistency outweighs perfection. These findings echo the message of the image: small, steady effort accumulates into substantial change.

6.0 Overcoming the Myth of Sudden Transformation

Modern culture often celebrates overnight success, overshadowing the incremental progress behind it. Yet, as Clear (2018) emphasises in Atomic Habits, real transformation results from marginal gains—a philosophy famously adopted by British Cycling under coach Dave Brailsford. By improving each aspect of cycling performance by just 1%, the team achieved extraordinary success, including multiple Olympic gold medals and Tour de France victories (Clear, 2018). This example encapsulates how compounding small improvements create monumental outcomes.

Similarly, in education and personal productivity, small habits—like setting daily study goals or maintaining a morning routine—foster motivation and discipline. These habits form the backbone of self-efficacy, the belief in one’s ability to succeed (Bandura, 1997), which in turn drives sustained behavioural engagement.

The message embedded in this article — “Never underestimate the power of small habits”—is not merely motivational; it is scientifically grounded. Across financial management, intellectual development, and physical health, evidence consistently demonstrates that small, deliberate actions, compounded over time, produce transformational results. As behavioural and neuroscientific research confirms, success is rarely the product of radical change but rather the accumulation of consistent, incremental effort. Whether saving modest sums, reading a few pages daily, or walking consistently, these micro-habits build towards extraordinary achievements—proving that consistency, not intensity, drives lasting change.

References

Bandura, A. (1991) Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), pp. 248–287.

Bandura, A. (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman.

Cain, K. & Oakhill, J. (2006) Children’s comprehension problems in oral and written language: A cognitive perspective. New York: Guilford Press.

Clear, J. (2018) Atomic habits: An easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones. London: Random House.

Draganski, B. et al. (2004) ‘Changes in grey matter induced by training’, Nature, 427(6972), pp. 311–312.

Duhigg, C. (2012) The power of habit: Why we do what we do and how to change. London: Random House.

Ericsson, K.A., Krampe, R.T. & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993) ‘The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance’, Psychological Review, 100(3), pp. 363–406.

Fernandes, D., Lynch, J.G. & Netemeyer, R.G. (2014) ‘Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors’, Management Science, 60(8), pp. 1861–1883.

Gelles, D. (2016) ‘Warren Buffett’s secret: Reading’, The New York Times, 28 February.

Graybiel, A.M. (2008) ‘Habits, rituals, and the evaluative brain’, Annual Review of Neuroscience, 31, pp. 359–387.

Hardy, D. (2010) The compound effect. New York: Vanguard Press.

Lally, P. et al. (2010) ‘How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world’, European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), pp. 998–1009.

Lusardi, A. & Mitchell, O.S. (2014) ‘The economic importance of financial literacy’, Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), pp. 5–44.

Oja, P. et al. (2018) ‘Health benefits of different walking intensities and step counts’, Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(10), pp. 2090–2101.

Shefrin, H.M. & Thaler, R.H. (1988) ‘The behavioural life-cycle hypothesis’, Economic Inquiry, 26(4), pp. 609–643.

Stanovich, K.E. & Cunningham, A.E. (1992) ‘Studying the consequences of literacy within a literate society’, Memory & Cognition, 20(1), pp. 51–68.

Takemi, Y. (2018) Dietary and lifestyle trends in Japan. Tokyo: Springer.

Thaler, R.H. & Sunstein, C.R. (2008) Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. London: Penguin Books.

Tudor-Locke, C. & Bassett, D.R. (2004) ‘How many steps/day are enough?’, Sports Medicine, 34(1), pp. 1–8.

Wood, W. & Neal, D.T. (2016) ‘Healthy through habit: Interventions for initiating & maintaining health behaviour change’, Behavioral Science & Policy, 2(1), pp. 71–83.

World Health Organization (2020) Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: WHO.