In today’s competitive job market, employers value adaptability and flexibility as a core employability skill. The ability to respond effectively to changing circumstances, work with diverse teams, and manage uncertainty has become increasingly important in the globalised and dynamic world of work. Simply stating in an application that one is “flexible” or “adaptable” does not suffice; instead, recruiters seek evidence-based examples that demonstrate these qualities in action (Knight & Yorke, 2003). One of the most effective ways to illustrate adaptability is by using the STAR technique—a structured method for articulating experiences through Situation, Task, Action, and Result.

This essay explores how candidates can convincingly prove their adaptability to recruiters by applying the STAR framework, drawing on real-life experiences such as living abroad, working with diverse teams, or balancing multiple responsibilities, and grounding these in academic and professional guidance.

The Importance of Adaptability and Flexibility in Employability

Adaptability is recognised as a critical employability skill in the 21st-century labour market (Fugate, Kinicki & Ashforth, 2004). According to Hillage and Pollard (1998), employability encompasses not just the possession of qualifications and experience but also the capacity to learn and adapt to changing organisational and technological contexts. Employers increasingly prioritise candidates who can demonstrate resilience, flexibility, and problem-solving in challenging situations (OECD, 2018).

For instance, research by Pulakos et al. (2000) identifies adaptability as a multidimensional construct, encompassing the ability to handle work stress, learn new tasks, and deal effectively with unpredictable or dynamic environments. These capabilities align with modern workplace demands, where rapid change—driven by digital transformation, globalisation, and evolving work practices—requires continuous adaptation (De Vos, De Hauw & Van der Heijden, 2011).

Recruiters thus look for candidates who can not only cope with change but also thrive in it, demonstrating an ongoing willingness to acquire new knowledge and collaborate across cultural and organisational boundaries (Bridgstock, 2009).

Moving Beyond Statements: Proving Adaptability and Flexibility

It is common for candidates to claim adaptability in their CVs or interviews; however, without specific evidence, such statements lack credibility. According to University of Kent Careers and Employability Service (2022), recruiters seek concrete examples of when an applicant demonstrated flexibility, creativity, or problem-solving. Therefore, candidates must use reflective examples drawn from personal, academic, or professional experiences that reveal how they adapted and what they learned.

Experiences that effectively demonstrate adaptability include:

- Living abroad during an exchange programme, showing openness to new cultures and environments.

- Moving to another country to study, illustrating resilience and cultural agility.

- Balancing study commitments with part-time work, revealing time management and prioritisation skills.

- Working with people of diverse ages and cultures, showing communication and teamwork adaptability.

- Engaging in placements, internships, or voluntary work, demonstrating applied flexibility in real-world settings.

Such examples are valuable because they reveal both the behavioural competencies (what was done) and the cognitive processes (how decisions were made) behind adaptive behaviour (Griffin & Hesketh, 2003).

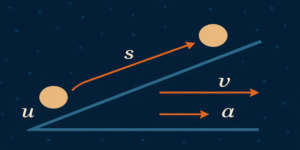

The STAR Technique: Structure and Purpose

The STAR technique—an acronym for Situation, Task, Action, Result—provides a structured approach to describing experiences. It allows candidates to communicate their adaptability clearly and compellingly. According to Clark (2018), STAR helps interviewees avoid vague generalisations by prompting them to organise their thoughts and highlight the most relevant aspects of their experience.

- Situation: Describe the context or background of the event.

- Task: Explain the challenge, goal, or problem that needed to be addressed.

- Action: Detail the specific steps you took to address the challenge.

- Result: Conclude with the outcomes or what you achieved and learned.

This structure ensures that the narrative remains concise, relevant, and outcome-focused—qualities recruiters value in both written and spoken communication (NACE, 2020).

Applying STAR to Demonstrate Adaptability and Flexibility

The following example illustrates how the STAR framework can be applied to prove adaptability effectively:

Situation: The candidate initially applied to study Pharmacy at university but did not achieve the required grade in Chemistry. This unexpected setback necessitated a rapid reassessment of future plans.

Task: The goal was to identify an alternative degree programme aligned with personal interests and long-term career aspirations, while dealing with disappointment and uncertainty.

Action: After consulting with career advisors and researching alternatives, the candidate chose to pursue Biomedical Sciences at a different university through the Clearing process. They demonstrated independence and self-reflection by prioritising academic passion over geographical comfort.

Result: The decision led to successful enrolment, personal growth, and enhanced cultural understanding through exposure to a diverse student body. The experience strengthened resilience, decision-making, and commitment to career goals.

This example demonstrates adaptability through strategic problem-solving, emotional intelligence, and self-directed learning—qualities linked with employability success (Tomlinson, 2017).

Real-World Examples of Adaptability and Flexibility

To further illustrate how adaptability manifests in various contexts, consider the following examples supported by literature:

- Living abroad as part of an exchange programme encourages intercultural competence and open-mindedness (Byram, 1997). For example, students participating in Erasmus exchanges report enhanced adaptability and communication skills, which employers value (European Commission, 2019).

- Balancing part-time work and academic study reflects the ability to manage competing demands, a skill closely linked to employability and self-regulation (Zimmerman, 2002).

- Voluntary work experience often involves working with limited resources or diverse communities, which cultivates flexibility, empathy, and teamwork (Hustinx & Lammertyn, 2003).

- Internships and placements provide real-world exposure, requiring students to adapt academic theory to professional practice, a process known as boundary crossing (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011).

Each of these scenarios offers a platform for applying the STAR technique to demonstrate adaptability concretely.

Why STAR is Effective in Recruitment

Research indicates that behavioural interviewing, which uses structured techniques like STAR, is one of the most predictive methods for assessing candidate suitability (Campion et al., 1997). This approach enables recruiters to evaluate not only what candidates have done but also their underlying competencies, attitudes, and learning capacity (Lievens et al., 2015).

Using STAR also supports reflective employability learning—encouraging individuals to analyse experiences critically, identify transferable skills, and articulate them effectively (Yorke & Knight, 2006). For instance, reflecting on a challenging group project may reveal how one adapted communication styles to work with culturally diverse teammates—a key skill in international organisations.

In conclusion, proving adaptability to recruiters requires more than stating one’s flexibility; it involves demonstrating evidence-based behaviours that reflect one’s ability to adjust, learn, and thrive in new or challenging circumstances. The STAR technique serves as a powerful framework to structure these experiences and convey them convincingly during applications and interviews.

Through examples such as living abroad, working across cultures, or balancing competing responsibilities, candidates can showcase the practical dimensions of adaptability—highlighting their resilience, resourcefulness, and reflective capacity. In doing so, they transform abstract claims into compelling, credible narratives that set them apart in the job market.

References

Akkerman, S. F. & Bakker, A. (2011) Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 132–169.

Bridgstock, R. (2009) The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(1), 31–44.

Byram, M. (1997) Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Campion, M. A. et al. (1997) Structure in the selection interview: A meta-analysis of the research literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 900–919.

Clark, D. (2018) Interview success: Using the STAR technique effectively. The Guardian, 18 May.

De Vos, A., De Hauw, S. & Van der Heijden, B. (2011) Competency development and career success: The mediating role of employability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 438–447.

European Commission (2019) The Erasmus Impact Study. Brussels: European Commission.

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J. & Ashforth, B. E. (2004) Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14–38.

Griffin, B. & Hesketh, B. (2003) Adaptable behaviours for successful work and career adjustment. Australian Journal of Psychology, 55(2), 65–73.

Hillage, J. & Pollard, E. (1998) Employability: Developing a Framework for Policy Analysis. London: DfEE.

Hustinx, L. & Lammertyn, F. (2003) Collective and reflexive styles of volunteering. Voluntas, 14(2), 167–187.

Knight, P. & Yorke, M. (2003) Employability and Good Learning in Higher Education. Teaching in Higher Education, 8(1), 3–16.

Lievens, F. et al. (2015) Behavioural interview validity: Combining past behaviour and future intentions. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 88(1), 77–99.

NACE (2020) Career Readiness Competencies: Critical Thinking/Problem Solving. Available at: www.naceweb.org.

OECD (2018) The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Tomlinson, M. (2017) Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability. Education + Training, 59(4), 338–352.

University of Kent Careers and Employability Service (2022) Demonstrating skills to employers. Canterbury: University of Kent.

Yorke, M. & Knight, P. (2006) Embedding Employability into the Curriculum. York: Higher Education Academy.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002) Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64–70.