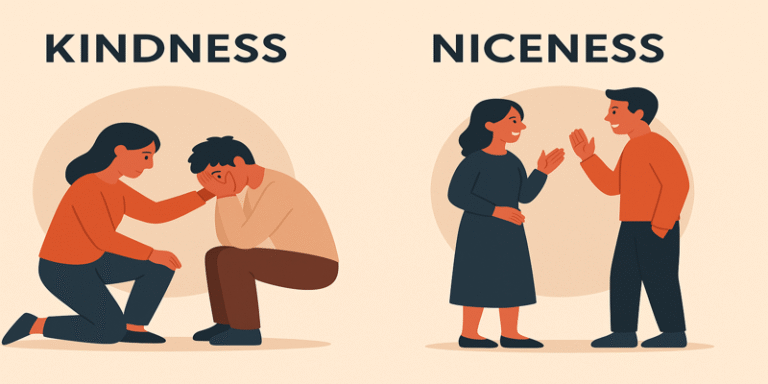

In the realm of human interaction, “being nice” and “being kind” are terms often used interchangeably. At a glance, both imply politeness, goodwill, and positive regard for others. However, beneath the surface, these concepts reflect very different intentions, psychological processes, and social outcomes. While niceness often aligns with social conformity and conflict avoidance, kindness stems from empathy, moral courage, and a genuine concern for others.

Understanding the distinction is important, not just for improving our personal relationships, but also for fostering more authentic, compassionate societies. This article examines the behavioural, emotional, and psychological differences between niceness and kindness, drawing on contemporary research in social psychology, neuroscience, and ethics.

1.0 The Psychology of Being Nice

Being “nice” is generally understood as displaying socially acceptable and agreeable behaviour. Nice individuals may smile often, agree with others even when they internally disagree, offer polite conversation, and avoid topics or actions that may trigger discomfort (Adams, 2016).

However, niceness is frequently tied to external motivations. These may include:

- A desire to be liked or accepted.

- A fear of confrontation or rejection.

- An attempt to uphold social norms or expectations.

Nice behaviours are often performative rather than sincere. While they may temporarily ease social tension, they can lack depth, authenticity, or ethical conviction. According to Bruneau et al. (2015), niceness does not necessarily correlate with prosocial action or moral courage; in fact, it may mask indifference or emotional disengagement, especially when difficult conversations or actions are needed.

2.0 The Psychology of Being Kind

Kindness, in contrast, is a virtue rooted in empathy, compassion, and altruism. Unlike niceness, which is externally focused, kindness arises from internal ethical values and a desire to alleviate suffering (Keltner et al., 2014). Kind people are often described as:

- Emotionally attuned to others’ needs.

- Generous with their time, attention, or resources.

- Courageous, especially when standing up for others.

- Unconcerned with recognition, acting without expecting rewards.

Research by Seppala (2016) and Curry et al. (2018) shows that acts of kindness are associated with increased emotional well-being, not only for the recipient but also for the giver. These acts build trust and social bonds, even when they are small, such as helping someone carry groceries or listening empathetically to a friend in distress.

3.0 Motivation: Approval vs Altruism

One of the most significant differences lies in motivation. Nice behaviour is often driven by social validation—a need to appear agreeable, to be liked, or to avoid conflict (Grant, 2020). This can lead to people-pleasing tendencies, where an individual says “yes” when they want to say “no”, leading to personal burnout or resentment.

Kindness, by contrast, is proactive and intentional. It may involve setting boundaries, telling the truth, or taking risks to protect or support others. DeSteno et al. (2010) suggest that emotions such as gratitude and compassion, which underpin kind behaviour, activate brain regions related to moral reasoning and empathy, rather than simple social compliance.

4.0 Behavioural Differences

| Characteristic | Being Nice | Being Kind |

| Motivation | Social acceptance, avoidance of conflict | Empathy, compassion, altruism |

| Typical Actions | Agreeing, complimenting, avoiding conflict | Helping, comforting, supporting |

| Authenticity | May be insincere or surface-level | Sincere, heartfelt, emotionally grounded |

| Moral Courage | Avoids discomfort | Faces discomfort for the benefit of others |

| Impact | Maintains short-term harmony | Builds long-term trust and connection |

While niceness focuses on external appearances, kindness focuses on genuine connection and care, often at the cost of temporary discomfort.

5.0 Societal Implications

Niceness, while socially rewarding in the short term, can have limiting effects on deeper social progress. For instance, in organisations or communities, an overemphasis on being nice can discourage honest feedback, suppress dissent, and maintain harmful status quos (Grant, 2020).

Kindness, on the other hand, encourages moral clarity and action. It promotes:

- Inclusive cultures where people feel heard and supported.

- Authentic leadership, where leaders take difficult but compassionate actions.

- Stronger communities, where trust and mutual aid are prioritised.

Aknin et al. (2013) found that cultures promoting kindness (rather than just politeness) tend to show higher levels of psychological well-being and social trust. Acts of kindness create a ripple effect, encouraging others to pay it forward, thus fostering prosocial behaviour across communities.

6.0 Kindness and Mental Health

Kindness is not only beneficial for society but also for mental health. Numerous studies, including those by Curry et al. (2018), show that engaging in kind behaviour:

- Reduces stress and anxiety.

- Increases feelings of purpose and fulfilment.

- Enhances self-esteem and connectedness.

Being nice, by contrast, may lead to emotional exhaustion if it stems from inauthentic motives or suppresses true feelings. Constantly trying to be agreeable can result in people-pleasing, poor boundaries, and even depression.

7.0 Cultivating Kindness Over Niceness

To shift from niceness to kindness, individuals can practise:

- Mindful listening: genuinely engaging with others’ experiences.

- Authentic communication: being honest while remaining respectful.

- Empathic action: asking, “What would truly help this person?” rather than, “How can I appear helpful?”

- Courageous compassion: speaking up for others, even when it’s uncomfortable.

Unlike niceness, kindness requires emotional intelligence, ethical reflection, and a willingness to act from integrity, not popularity.

While both being nice and being kind may appear similar on the surface, they are fundamentally different in origin, purpose, and impact. Niceness is about being liked; kindness is about doing what is right. Niceness smooths social interactions, often at the expense of depth and honesty. Kindness, in contrast, leads to authentic relationships, stronger communities, and greater personal fulfilment.

In a world increasingly dominated by superficial connections and curated appearances, choosing kindness over niceness may be a radical but necessary act of genuine humanity.

References

Adams, S. (2016) What’s the Difference Between Being Nice and Being Kind?, Forbes.

Aknin, L. B., Barrington-Leigh, C. P., Dunn, E. W., Helliwell, J. F., Biswas-Diener, R., Kemeza, I., … & Norton, M. I. (2013) ‘Prosocial spending and well-being: Cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), pp. 635–652.

Bruneau, E., Cikara, M. and Saxe, R. (2015) ‘Parochial empathy predicts reduced altruism and the endorsement of passive harm’, Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(4), pp. 499–507.

Curry, O. S., Rowland, L. A., Van Lissa, C. J., Zlotowitz, S., McAlaney, J. and Whitehouse, H. (2018) ‘Happy to help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, pp. 320–329.

DeSteno, D., Bartlett, M. Y., Baumann, J., Williams, L. A. and Dickens, L. (2010) ‘Gratitude as moral sentiment: Emotion-guided cooperation in economic exchange’, Emotion, 10(2), pp. 289–293.

Grant, A. (2020) The Difference Between Being Nice and Being Kind. The New York Times.

Keltner, D., Kogan, A., Piff, P. K. and Saturn, S. R. (2014) ‘The sociocultural appraisals, values, and emotions (SAVE) framework of prosociality: Core processes from gene to meme’, Annual Review of Psychology, 65, pp. 425–460.

Seppala, E. (2016) ‘The Power of Kindness’, Scientific American.