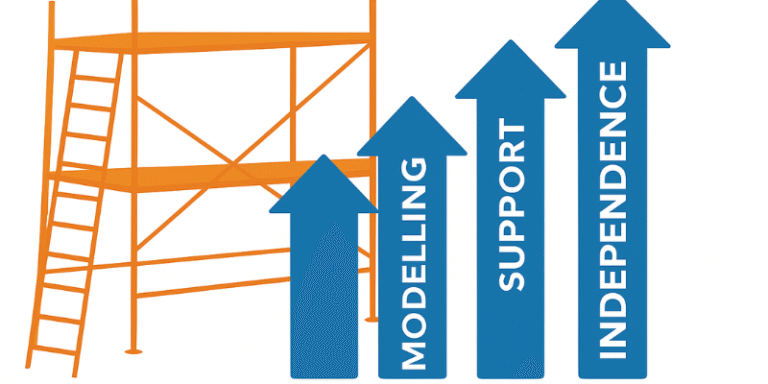

Scaffolding is a foundational educational strategy for teachers and trainers that plays a crucial role in supporting learners as they progress from novice to expert in a given area of study. The term was first introduced by Wood, Bruner, and Ross (1976), drawing an analogy to the temporary physical structure used in construction that supports workers while a building is being erected. In education, scaffolding is designed to provide learners with temporary, adjustable support that enables them to perform tasks they would not be able to accomplish independently, but which they can achieve with guidance.

At its core, scaffolding aligns closely with Vygotsky’s (1978) concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)—the range of tasks a learner can perform with help, but not yet independently. Vygotsky posited that meaningful learning occurs within this zone, and that interaction with more knowledgeable others (teachers, peers, mentors) facilitates the development of new skills and knowledge. Thus, scaffolding acts as the bridge between what learners can currently do and what they are capable of achieving with structured support.

Forms of Scaffolding in Educational Practice

Scaffolding can take many practical forms in both classroom and online learning environments. These include modelling, prompting, guided practice, gradual release of responsibility, feedback, and chunking.

1.0 Modelling

One of the most fundamental scaffolding techniques is modelling. This involves the teacher demonstrating a task or skill, offering learners a clear and concrete example to emulate. Bandura’s (1977) Social Learning Theory underscores the value of observational learning—learners can acquire new behaviours and skills by watching competent models perform them. For instance, a teacher might demonstrate how to solve a mathematics problem step-by-step while verbalising their thought process. This not only shows the process but also externalises the cognitive strategies involved.

2.0 Prompting

Prompting refers to the use of cues, hints, or questions to nudge students towards the next step in their thinking or task completion. Rather than providing answers outright, effective prompting encourages learners to reflect, reason, and make their own connections. Rosenshine and Meister (1994) highlighted the effectiveness of prompting in their studies on reciprocal teaching, showing that it can significantly enhance comprehension and engagement.

3.0 Guided Practice

Guided practice offers learners the chance to perform tasks with substantial teacher involvement. During this stage, the teacher offers immediate feedback, correction, and encouragement, while gradually shifting more control to the learner. This approach allows for real-time adjustment of support, ensuring that learners do not become frustrated or disengaged (Vygotsky, 1978). This method is especially useful in skill-based subjects like writing, coding, and experimental sciences.

4.0 Gradual Release of Responsibility

This pedagogical model involves shifting the responsibility of learning from the teacher to the student in stages: “I do” (teacher models), “We do” (teacher and student work together), “You do it together” (students collaborate), and finally “You do it alone” (independent work). Pearson and Gallagher (1983) formalised this model, arguing that such a structure fosters learner autonomy and confidence, allowing learners to internalise strategies before applying them independently.

5.0 Feedback

Constructive feedback is another cornerstone of scaffolding. Hattie and Timperley (2007) found that timely, specific feedback has a powerful impact on student learning outcomes. Effective feedback helps learners understand what they have done correctly, where they have gone wrong, and how they can improve. It closes the gap between current performance and desired goals, while also affirming effort and promoting a growth mindset.

6.0 Chunking

Miller’s (1956) theory on the limits of working memory explains the value of chunking—breaking down complex information into smaller, more manageable pieces. When tasks are too large or multifaceted, learners can become overwhelmed and demotivated. By segmenting content into digestible chunks, educators can support cognitive processing and enhance retention. For example, a complex essay writing task might be broken down into smaller components such as outlining, thesis development, evidence gathering, and paragraph structure.

Theoretical Foundations and Contemporary Applications

Scaffolding has evolved from its roots in developmental psychology to become a widely used and researched pedagogical strategy. Its theoretical grounding in constructivist learning theories has made it particularly relevant in today’s learner-centred educational paradigms.

Modern digital learning platforms now also incorporate scaffolding principles. Intelligent tutoring systems, for instance, use adaptive algorithms to offer hints, examples, and incremental challenges based on real-time learner performance (VanLehn, 2011). Similarly, online collaborative tools can provide peer scaffolding opportunities, facilitating social constructivist learning through group work and shared inquiry (Dillenbourg, 1999).

Moreover, scaffolding is essential in differentiated instruction. Teachers adjust their support based on individual learners’ needs, recognising that students enter the classroom with varying prior knowledge, learning preferences, and cognitive abilities (Tomlinson, 2014). In inclusive education, scaffolding ensures equity by making learning accessible to students with diverse abilities.

Challenges and Considerations

While scaffolding is a powerful instructional approach, it must be applied judiciously. Over-scaffolding—providing too much help—can hinder learners from developing independence and self-efficacy. Conversely, under-scaffolding can lead to confusion, anxiety, and disengagement. As such, effective scaffolding requires careful diagnosis of student needs, ongoing formative assessment, and flexible responsiveness.

Additionally, cultural differences in teaching and learning styles may affect how scaffolding is interpreted and implemented. Educators must consider the socio-cultural context and be sensitive to how authority, autonomy, and collaboration are viewed in different educational settings (Hammond & Gibbons, 2005).

Scaffolding is a dynamic, evidence-based instructional strategy that enhances learner achievement by bridging the gap between current competence and the potential for independent performance. By implementing techniques such as modelling, prompting, guided practice, and providing timely feedback, educators can support learners through challenges and foster mastery. As education continues to evolve in both physical and digital environments, scaffolding remains essential in promoting deep learning, critical thinking, and learner confidence.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Dillenbourg, P. (1999). Collaborative Learning: Cognitive and Computational Approaches. Oxford: Elsevier.

Hammond, J. & Gibbons, P. (2005). Putting scaffolding to work: The contribution of scaffolding in articulating ESL education. Prospect, 20(1), pp. 6–30.

Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), pp. 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), pp. 81–97.

Pearson, P. D. & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The Instruction of Reading Comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8(3), pp. 317–344.

Rosenshine, B. & Meister, C. (1994). Reciprocal Teaching: A Review of the Research. Review of Educational Research, 64(4), pp. 479–530.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners. 2nd ed. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

VanLehn, K. (2011). The Relative Effectiveness of Human Tutoring, Intelligent Tutoring Systems, and Other Tutoring Systems. Educational Psychologist, 46(4), pp. 197–221.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S. & Ross, G. (1976). The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), pp. 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x