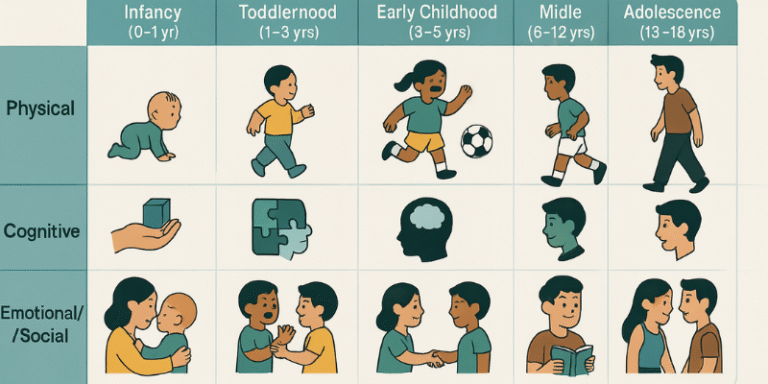

Child development refers to the biological, psychological, and emotional changes that occur in human beings between birth and the end of adolescence. It is a continuous process with distinct stages, each characterised by specific milestones across multiple domains—physical, cognitive, language, and emotional/social. Understanding these developmental stages is essential for parents, educators, and professionals working with children, enabling them to support children’s needs appropriately and identify any deviations that may require intervention (Sheridan et al., 2011).

1.0 Infancy (0–1 Year)

Infancy is marked by rapid physical growth and neurological development. Newborns typically double their birth weight by six months and triple it by the end of the first year. Milestones include gaining head control, sitting unaided, crawling, and in many cases, taking first steps by twelve months (Berk, 2018).

Cognitively, infants begin to develop object permanence—understanding that objects continue to exist even when out of sight—around 6 to 8 months, a concept central to Piaget’s sensorimotor stage (Piaget, 1952). They also begin to recognise familiar faces and explore the environment through sensory input, laying the groundwork for more complex learning.

Language development begins with cooing and babbling, progressing to recognisable words like “mama” or “dada” by the end of the first year (Kuhl, 2004). Socially, infants start forming attachments to caregivers, an emotional bond crucial for social and emotional development. Bowlby’s attachment theory highlights the importance of secure attachment in fostering resilience and healthy relationships later in life (Bowlby, 1969).

2.0 Toddlerhood (1–3 Years)

Toddlerhood is characterised by increased mobility and growing independence. Children typically begin walking unaided, climbing stairs, feeding themselves, and developing fine motor skills, such as stacking blocks or using crayons (Sheridan et al., 2011).

Cognitively, toddlers begin to understand cause and effect and follow simple instructions. They also demonstrate early problem-solving abilities, often through trial and error. Piaget classifies this period as the final phase of the sensorimotor stage and the start of the preoperational stage, where symbolic thinking starts to emerge (Piaget, 1952).

Language acquisition is rapid during this phase. Vocabulary expands from around 50 words at 18 months to over 200 by age 2, and toddlers begin forming simple two- or three-word sentences (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2001). This language boom is supported by responsive caregiving and rich verbal environments.

Socially and emotionally, toddlers exhibit assertiveness—often labelled as the “no” phase—as they explore autonomy. They imitate adult behaviour, show affection, and begin to experience empathy. Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development identifies this stage as one of “autonomy vs shame and doubt,” where children learn to exercise personal control (Erikson, 1950).

3.0 Early Childhood / Preschool (3–5 Years)

During early childhood, children demonstrate enhanced physical coordination, such as hopping, running smoothly, and using tools like scissors. Fine motor control also improves, allowing them to draw shapes and dress themselves (Meggit, 2012).

Cognitive development during this stage is largely imaginative. Children engage in symbolic play, begin to count, and understand basic time concepts. Although their reasoning remains intuitive rather than logical, they are curious and increasingly capable of understanding rules and routines (Piaget, 1952).

Language becomes more sophisticated. Children use full sentences, ask complex questions, and begin storytelling. The preschool years are critical for language development, and early exposure to books and dialogue significantly influences later literacy skills (Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998).

Emotionally, children begin managing their feelings and interacting cooperatively with peers. They engage in shared activities and understand the concept of taking turns. Their sense of self strengthens, and self-esteem starts to develop through social comparison and adult feedback (Papalia et al., 2020).

4.0 Middle Childhood (6–12 Years)

Middle childhood sees steady physical growth and increased strength and coordination, which supports participation in structured activities like sports and dance (Berk, 2018).

Cognitive development is marked by what Piaget termed concrete operational thinking. Children can now perform logical operations on tangible objects, understand conservation of mass and volume, and organise thoughts systematically (Piaget, 1952). Their attention span improves, and they begin mastering academic skills such as reading, writing, and mathematics.

Language skills become more refined. Vocabulary expands significantly, and children use complex sentence structures. They can write narratives, explain ideas, and engage in meaningful discussions (Snow, 2010).

Socially, peer relationships become central to self-identity. Children develop a better understanding of fairness and empathy, and they learn to navigate group dynamics. Emotional development involves managing more nuanced emotions like embarrassment, guilt, and pride. Erikson refers to this as the stage of “industry vs inferiority,” where mastering tasks and receiving recognition builds self-confidence (Erikson, 1950).

5.0 Adolescence (13–18 Years)

Adolescence begins with puberty, leading to dramatic physical changes such as increased height, hormonal changes, and sexual maturation (Papalia et al., 2020). These transformations often cause emotional turbulence as adolescents adjust to new identities.

Cognitively, adolescents enter Piaget’s formal operational stage, allowing abstract thinking, hypothesis testing, and ethical reasoning. They also develop metacognition—the ability to think about their own thinking—which supports academic achievement and identity formation (Piaget, 1952; Steinberg, 2014).

Language becomes an important tool for self-expression, debate, and persuasion. Adolescents often refine their use of sarcasm, idioms, and subcultural language (Nippold, 2007).

Emotionally, adolescents strive for independence, and identity becomes central. Peer influence intensifies, and family relationships may experience tension. According to Erikson, the psychosocial task at this stage is “identity vs role confusion,” where adolescents explore values, beliefs, and future goals (Erikson, 1950).

Comparative Overview of Child Development Stages

| Domain | Infancy (0–1 yr) | Toddlerhood (1–3 yrs) | Early Childhood (3–5 yrs) | Middle Childhood (6–12 yrs) | Adolescence (13–18 yrs) |

| Physical | Rapid physical growth; gains head control, begins crawling and walking | Walks and climbs; fine motor skills improve (scribbling, feeding self) | Enhanced coordinatio; hops, dresses self, uses scissors | Steady growth; increased strength and agility | Puberty begins; growth spurts and sexual maturity |

| Cognitive | Explores with senses; starts developing object permanence | Follows instructions; solves simple problems; symbolic thinking emerges | Engages in imaginative play; basic counting; understands time concepts | Thinks logically about concrete events; develops reading and math skills; longer attention span | Uses abstract reasoning; plans for the future; exhibits metacognition |

| Language | Cooing and babbling; first words around 12 months | Vocabulary growth; two-word phrases; forms simple sentences | Speaks in full sentences; asks questions; tells stories | Uses complex sentences; participates in academic discussions | Employs advanced vocabulary; debates; expresses nuanced ideas |

| Emotional/Social | Bonds with caregivers; stranger anxiety; smiles socially | Shows empathy; imitates others; asserts independence (notably says “no”) | Plays cooperatively; understands rules; regulates basic emotions | Forms peer relationships; develops self-esteem; understands others’ perspectives | Forms identity; seeks independence; experiences peer influence |

Child development unfolds in a predictable sequence of stages, each with distinct challenges and achievements. While the timeline of milestones may vary among individuals, understanding typical development helps parents, educators, and professionals provide appropriate support and identify concerns early. Integrating research from developmental psychology, neuroscience, and education ensures a holistic understanding of this dynamic process.

References

Berk, L.E. (2018). Development Through the Lifespan. 7th ed. London: Pearson.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Erikson, E.H. (1950). Childhood and Society. New York: Norton.

Kuhl, P.K. (2004). Early language acquisition: Cracking the speech code. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(11), pp.831–843.

Meggitt, C. (2012). Child Development: An Illustrated Guide. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Nippold, M.A. (2007). Later Language Development: School-Age Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. 3rd ed. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Papalia, D.E., Feldman, R.D. and Martorell, G. (2020). A Child’s World: Infancy through Adolescence. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International Universities Press.

Sheridan, M., Howard, J. and Alderson, D. (2011). Play in Early Childhood: From Birth to Six Years. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Snow, C.E. (2010). Academic language and the challenge of reading for learning about science. Science, 328(5977), pp.450–452.

Steinberg, L. (2014). Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Tamis-LeMonda, C.S., Bornstein, M.H. and Baumwell, L. (2001). Maternal responsiveness and children’s achievement of language milestones. Child Development, 72(3), pp.748–767.

Whitehurst, G.J. and Lonigan, C.J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69(3), pp.848–872.