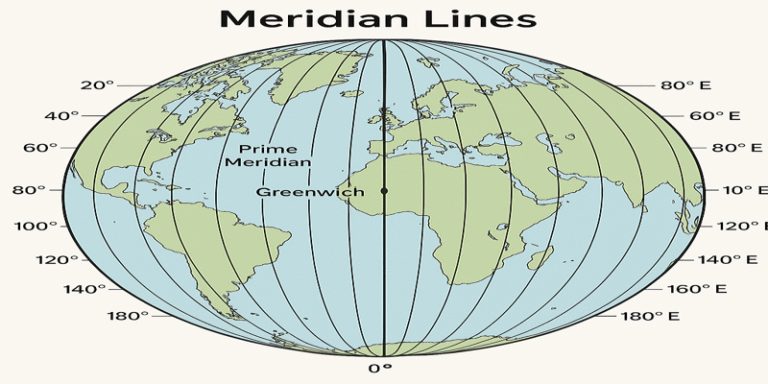

In the realm of geography and cartography, the concept of meridian lines, or lines of longitude, is fundamental. These imaginary lines form the backbone of the global coordinate system, enabling accurate navigation, mapping, and the division of time across the Earth. A meridian line is a longitudinal line running from the North Pole to the South Pole, intersecting the equator and all lines of latitude at right angles. Among these, the Prime Meridian—set at 0° longitude and passing through Greenwich, England—serves as the reference point from which all other longitudes are measured.

Origins and Definition of Meridian Lines

The term “meridian” is derived from the Latin meridies, meaning “midday” or “south,” reflecting the line’s historical use in tracking the position of the sun at noon (Taylor, 2005). In geography, meridians are semi-circular lines that converge at the poles and are spaced longitudinally at equal angular distances. Each meridian, when paired with its opposite, completes a great circle that encircles the Earth vertically.

There are 360 degrees of longitude, with the Prime Meridian dividing the Earth into the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. Meridians to the east of Greenwich are numbered from 1° to 180° east (E), and those to the west are numbered 1° to 180° west (W).

Historical Development of the Prime Meridian

Before international agreement on a standard meridian, different countries used local reference lines for their maps and navigation. It was not until the International Meridian Conference of 1884, held in Washington D.C., that the Greenwich Meridian was officially adopted as the Prime Meridian (Howse, 1997). The decision was largely influenced by the extensive use of British naval charts and the prominence of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, which had been producing navigational data since the late 17th century.

As a result, the Greenwich Meridian became the basis not only for mapping and navigation but also for Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), which standardised the measurement of time globally.

The Role of Meridians in the Global Coordinate System

Meridians, together with parallels of latitude, form the geographic grid system. Latitude lines run horizontally around the Earth, while meridians run vertically, intersecting at right angles. This grid enables precise identification of any location on the Earth’s surface using coordinates expressed in degrees (°), minutes (‘), and seconds (“).

For example, the city of Cairo, Egypt, is located at approximately 30°02′N latitude and 31°14′E longitude. These coordinates help in navigation, mapping, and in fields such as aviation, shipping, and even telecommunications (Monmonier, 1996).

Meridian Lines and Time Zones

One of the most critical uses of meridian lines is in the determination of time zones. Since the Earth rotates 360 degrees every 24 hours, it rotates approximately 15 degrees every hour. Thus, the world is divided into 24 time zones, each spanning roughly 15 degrees of longitude. The Prime Meridian at Greenwich serves as the starting point (GMT or UTC+0), with time zones increasing or decreasing by one hour for every 15 degrees east or west, respectively (Steers, 1970).

This division has practical implications. For example, when it is noon at Greenwich, it is already 3 p.m. in Moscow (UTC+3) and 7 a.m. in New York City (UTC–5). Time zone boundaries are adjusted to accommodate political and economic regions, but the foundational principle is based on meridian lines.

Applications in Navigation and Cartography

Meridian lines are essential for navigation, both on land and at sea. Navigators and pilots rely on longitude and latitude to chart courses and determine positions. In the age of Global Positioning Systems (GPS), satellites use geodetic coordinates—based on meridians and parallels—to provide precise location data to users worldwide (Hofmann-Wellenhof et al., 2001).

In cartography, meridian lines influence map projections and the orientation of maps. For instance, Mercator projections depict meridians as equally spaced vertical lines, which aids in marine navigation despite distorting size near the poles.

Technological Integration and Modern Use

With the rise of digital cartography and GIS (Geographic Information Systems), meridian lines continue to play a crucial role. Mapping software like Google Earth and satellite imagery platforms use longitude data to map locations and measure distances. Furthermore, many scientific studies—including those on climate change, urban planning, and disaster management—rely on geospatial data aligned with meridians and parallels.

Meridian lines also support space exploration. When mapping planets and other celestial bodies, scientists establish planetary coordinate systems that function similarly to Earth’s, using a prime meridian to define longitude (Seidelmann et al., 2007).

The Cultural and Symbolic Significance

Beyond their practical uses, meridian lines have acquired symbolic significance. The Royal Observatory in Greenwich attracts thousands of visitors who stand astride the Prime Meridian, symbolically placing one foot in the Eastern Hemisphere and the other in the Western Hemisphere. This line represents not just a geographical boundary but also a shared global standard.

Challenges and Adjustments

The Prime Meridian, as originally marked at Greenwich, does not align perfectly with the modern 0° longitude line used by GPS systems, which lies about 102 metres east. This discrepancy is due to differences between astronomical observations and satellite measurements, as well as the shift from traditional surveying methods to geodetic systems based on the Earth’s shape and gravity field (Malys et al., 2015). Despite this, the Greenwich location retains its historical and symbolic status.

Meridian lines are more than just imaginary lines on a map—they are essential components of the global geographic framework. From enabling timekeeping and navigation to supporting digital mapping and scientific research, meridians underpin many aspects of modern life. The adoption of the Prime Meridian at Greenwich marked a turning point in creating a unified global standard, one that continues to guide the way we understand and interact with our world.Top of Form

Bottom of Form

References

Hofmann-Wellenhof, B., Lichtenegger, H. and Collins, J. (2001). GPS: Theory and Practice. 5th ed. New York: Springer.

Howse, D. (1997). Greenwich Time and the Longitude. London: Philip Wilson.

Malys, S., Slater, J., Smith, R., Kenyon, S., Milbert, D. and Dragosky, A. (2015). ‘Why the Greenwich meridian moved’, Journal of Geodesy, 89(12), pp.1215–1223.

Monmonier, M. (1996). How to Lie with Maps. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Seidelmann, P.K. et al. (2007). ‘Report of the IAU/IAG Working Group on cartographic coordinates and rotational elements: 2006’, Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy, 98(3), pp.155–180.

Steers, J.A. (1970). An Introduction to the Study of Map Projections. 13th ed. London: University of London Press.

Taylor, E.G.R. (2005). The Mathematical Practitioners of Tudor and Stuart England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.