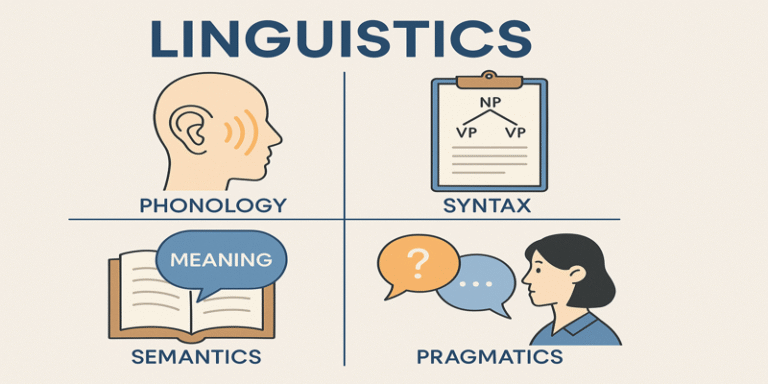

Linguistics, the scientific study of language, encompasses a broad spectrum of subfields and theoretical frameworks that address how language is structured, acquired, processed, and used. This article explores the principal domains within linguistics, including phonetics and phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, and applied linguistics, while also recognising the emerging trends in computational and cognitive linguistics.

1.0 Phonetics and Phonology

Phonetics is the study of speech sounds, focusing on their production (articulatory phonetics), transmission (acoustic phonetics), and perception (auditory phonetics). Phonology, closely related, examines how these sounds function within particular languages and how they are mentally represented (Akmajian et al., 2017). For example, the distinction between aspirated and unaspirated consonants in English (as in “pin” vs “spin”) is a phonological phenomenon. Phonological rules, such as assimilation or vowel harmony, form key components of language-specific sound systems (Aronoff & Rees-Miller, 2020).

2.0 Morphology

Morphology explores the internal structure of words and the rules that govern their formation. It distinguishes between inflectional morphology, which deals with grammatical changes (e.g. “walk” to “walked”), and derivational morphology, which creates new words (e.g. “happy” to “unhappiness”) (Radford et al., 2009). Morphemes—the smallest units of meaning—are central to this field. Morphology serves as a bridge between phonology and syntax, highlighting the systemic nature of language (McGregor, 2024).

3.0 Syntax

Syntax is the study of sentence structure and the rules that determine word order and hierarchical organisation. It examines how smaller units like words combine into larger structures, such as phrases and clauses. Generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky, revolutionised syntactic theory by introducing concepts like deep structure, surface structure, and transformational rules (Lyons, 1968; Trask, 1999). The concept of Universal Grammar suggests that humans are innately equipped with linguistic structures common to all languages (Aronoff & Rees-Miller, 2020).

4.0 Semantics and Pragmatics

Semantics concerns itself with meaning at the word, phrase, and sentence level. It explores relationships like synonymy, antonymy, and polysemy, as well as compositional meaning (Farmer et al., 2017). In contrast, pragmatics looks at meaning in context—how utterances are interpreted based on speaker intentions, shared knowledge, and situational factors. Speech act theory, implicature, and deixis are pivotal concepts in pragmatics (Finch, 2017). For instance, the sentence “Can you pass the salt?” is interpreted as a request, not a question about ability.

5.0 Sociolinguistics

Sociolinguistics examines how language varies and changes in social contexts. It investigates phenomena such as dialects, code-switching, language and gender, and language and power (Litosseliti, 2024). William Labov’s foundational work in this field illustrated how linguistic variation correlates with social variables like class, ethnicity, and region (Britain & Clahsen, 2009). Current research also addresses language policy, language death, and multilingualism, emphasising the sociopolitical dimensions of language use.

6.0 Psycholinguistics and Neurolinguistics

Psycholinguistics focuses on how language is acquired, understood, and produced by the human brain. This includes first language acquisition in children, second language learning, and language processing during real-time communication. Neurolinguistics, a related field, studies the neural mechanisms that underlie linguistic competence and performance. Disorders like aphasia reveal how different brain areas are involved in various linguistic functions (Chapelle, 2013). These disciplines benefit from advancements in neuroimaging techniques like fMRI and EEG.

7.0 Applied Linguistics

Applied linguistics seeks practical solutions to language-related problems in education, translation, health, and technology. It encompasses fields such as language teaching (TESOL), language assessment, and discourse analysis (Schmitt & Celce-Murcia, 2019). Critical applied linguistics further investigates issues of power, identity, and ideology in language education (Grabe & Kaplan, 2000). The growing demand for second language instruction and multilingual literacy underscores the relevance of this subfield.

8.0 Cognitive and Computational Linguistics

Cognitive linguistics posits that language is rooted in human cognition and shaped by perception, embodiment, and conceptualisation (Rudzka-Ostyn, 1988). Concepts such as image schemas and metaphor play central roles in this theory. Meanwhile, computational linguistics applies algorithms to analyse and generate language, forming the basis for technologies like machine translation, speech recognition, and chatbots. Natural Language Processing (NLP) is a fast-growing area intersecting with artificial intelligence (Atkinson et al., 2014).

9.0 Research Methods and Linguistic Theory

Linguistic research employs a wide range of methodologies, from fieldwork and corpus analysis to experimental design and formal modelling. Qualitative and quantitative approaches alike are used to explore hypotheses and analyse data (Litosseliti, 2024). Theoretical frameworks in linguistics range from structuralism and functionalism to post-structuralist and critical approaches. Each perspective offers unique insights into the multifaceted nature of language.

Linguistics is a vibrant and evolving field that provides critical insights into the structure, function, and use of language. From phonetic articulation to social dynamics and cognitive processing, the study of language touches on virtually every aspect of human experience. As global communication and digital technologies continue to expand, so too does the relevance of linguistic research across disciplines. By appreciating its many subfields and their interconnectedness, scholars and practitioners can better navigate the complexities of human communication.

References

Akmajian, A., Farmer, A. K., Bickmore, L., Demers, R. A., & Harnish, R. M. (2017). Linguistics: An Introduction to Language and Communication. MIT Press.

Aronoff, M. & Rees-Miller, J. (2020). The Handbook of Linguistics. Wiley-Blackwell.

Atkinson, M., Roca, I., & Kilby, D. (2014). Foundations of General Linguistics. Routledge.

Britain, D. & Clahsen, H. (2009). Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Chapelle, C. A. (2013). The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Wiley-Blackwell. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316094032

Farmer, A. K., Bickmore, L., & Akmajian, A. (2017). Linguistics: An Introduction to Language and Communication. MIT Press.

Finch, G. (2017). Key Concepts in Language and Linguistics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Grabe, W., & Kaplan, R. B. (2000). Applied linguistics and the annual review of applied linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/annual-review-of-applied-linguistics/article/applied-linguistics

Litosseliti, L. (2024). Research Methods in Linguistics. Bloomsbury.

Lyons, J. (1968). Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge University Press.

McGregor, W. B. (2024). Linguistics: An Introduction. Bloomsbury Academic.

Radford, A., Atkinson, M., Britain, D., Clahsen, H., & Spencer, A. (2009). Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Rudzka-Ostyn, B. (1988). Topics in Cognitive Linguistics. John Benjamins Publishing.

Schmitt, N., & Celce-Murcia, M. (2019). An Introduction to Applied Linguistics. Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429424465-1

Trask, R. L. (1999). Key Concepts in Language and Linguistics. Routledge.