Across psychology, neuroscience, psychotherapy and education, research consistently demonstrates that the ability to identify and label emotions is central to emotion regulation, psychological resilience, and interpersonal effectiveness. Tools such as The Feel Wheel provide a structured and accessible way to develop this essential skill. By offering a visual map of primary and secondary emotions, The Feel Wheel supports individuals in moving beyond vague emotional descriptions towards greater emotional precision.

The theory of constructed emotion (Barrett, 2017) suggests that emotions are shaped by conceptual knowledge and language. Empirical studies on affect labelling show that naming emotions reduces amygdala activation and increases prefrontal engagement, thereby supporting regulatory control (Lieberman et al., 2007; Black, 2013). The construct of emotional granularity—the ability to distinguish subtle emotional states—has been associated with lower maladaptive coping and improved mental health outcomes (Kashdan, Barrett & McKnight, 2015; Zaki et al., 2013).

Clinical texts emphasise that modern cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and related therapies integrate emotion identification as a foundational skill (Beck, 2011; Leahy, Tirch & Napolitano, 2011; Hofmann, 2015). Educational research similarly shows that structured emotional literacy programmes enhance well-being and social functioning in children (Rivers et al., 2012; Nook & Somerville, 2019). Together, this interdisciplinary evidence positions emotion identification not as a soft skill, but as a scientifically grounded pathway to emotional well-being.

1.0 The Power of Identifying Emotions: A Pathway to Emotional Well-being

Emotions are fundamental to human experience. They shape how we think, act, relate to others and interpret the world. Yet many people struggle to answer a deceptively simple question: What exactly am I feeling? We often default to broad terms like “stressed” or “upset”, overlooking the rich nuances of our inner lives. The act of identifying emotions—accurately naming and differentiating feelings—can be transformative. It strengthens emotional intelligence, enhances mental health, and improves relationships.

2.0 The Science Behind Identifying Emotions

Contemporary emotion science challenges the idea that emotions are fixed biological reactions. According to Barrett (2017), emotions are constructed by the brain, drawing on past experiences, language and social context. This means that the vocabulary we use to describe feelings shapes how we experience them. A person who can distinguish between “irritated”, “frustrated” and “resentful” is engaging in a more precise emotional construction than someone who simply says “angry”.

Neuroscientific research supports this view. Studies on affect labelling show that putting feelings into words reduces activity in the amygdala—the brain’s threat detection centre—while increasing activation in the prefrontal cortex, responsible for reasoning and regulation (Lieberman et al., 2007). In practical terms, naming an emotion such as “anxious” rather than remaining overwhelmed by it can reduce its intensity. Black (2013) found that individuals who labelled negative emotions recovered from low mood more quickly, suggesting that identification itself can be regulatory.

This process is not about suppressing emotion but about making it manageable. As Leahy, Tirch and Napolitano (2011) argue in their work on emotion regulation in psychotherapy, awareness and labelling are prerequisites for change. Without identifying the emotion, there is nothing specific to regulate.

3.0 Emotional Granularity: The Skill of Precision

The concept of emotional granularity refers to the ability to make fine-grained distinctions between emotional states. Kashdan, Barrett and McKnight (2015) describe it as the difference between experiencing life in “black and white” versus “high-definition colour”. Individuals high in granularity can differentiate between “disappointed”, “discouraged”, and “ashamed” rather than collapsing them into a single category.

Research indicates that higher emotional granularity is linked to more adaptive coping strategies. Zaki et al. (2013) found that emotion differentiation can act as a protective factor, reducing harmful behaviours associated with poor regulation. When individuals understand precisely what they feel, they are more likely to respond effectively.

Consider two workplace scenarios. In the first, an employee says, “I’m stressed.” In the second, the employee says, “I feel undervalued and frustrated because my efforts were not recognised.” The latter demonstrates granularity. The response to “stress” might be rest; the response to “feeling undervalued” might be a constructive conversation about expectations. Precision guides appropriate action.

4.0 The ‘Feel Wheel’ and Practical Tools

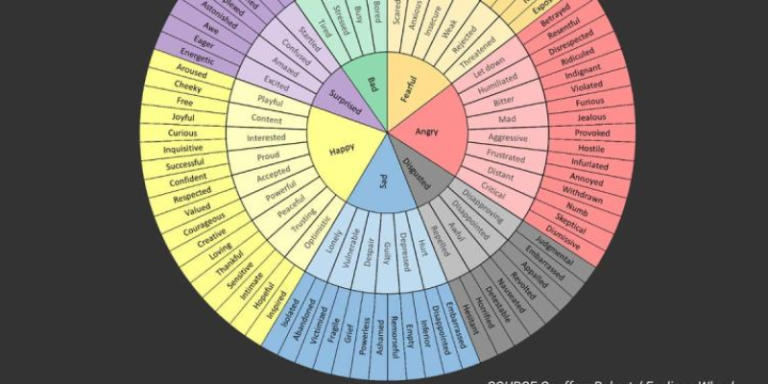

Tools such as the ‘Feel Wheel’ provide structured support for developing emotional vocabulary. By presenting primary emotions (e.g., sad, angry, happy, fearful) and branching into more specific descriptors (e.g., lonely, resentful, content, anxious), the wheel encourages deeper reflection.

From a developmental perspective, emotion concepts expand over time. Nook and Somerville (2019) show that as children acquire more emotion words, their regulatory abilities improve. Language becomes a scaffold for emotional understanding. In adults, similar principles apply: expanding emotional vocabulary enhances insight and flexibility.

5.0 Emotional Intelligence and Life Outcomes

The concept of emotional intelligence (EI), popularised by Goleman (1995), encompasses the capacity to recognise, understand and manage one’s own emotions while responding effectively to others. Emotional identification forms the foundation of EI. Without recognising one’s emotional state, higher-order skills such as empathy and relationship management are compromised.

Educational and organisational research suggests that emotional intelligence correlates with improved leadership, reduced burnout and stronger interpersonal relationships (Almheiri, 2021; Bood, 2025). Identifying emotions enables individuals to pause before reacting impulsively, thereby fostering constructive communication.

For example, in a family disagreement, a parent who recognises feeling “overwhelmed and worried” rather than simply “angry” may communicate concern rather than lash out. The relational outcome shifts accordingly.

6.0 Therapeutic Applications

In psychotherapy, identifying emotions is central to many approaches. Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) encourages clients to link thoughts, emotions and behaviours (Beck, 2011). Emotion identification allows clients to detect patterns such as catastrophising or negative self-appraisal. Hofmann (2015) emphasises that therapy is not solely about challenging thoughts but about understanding emotional processes that sustain them.

Moreover, emotion-focused components in therapy explicitly train clients to expand emotional awareness. Vine (2016) describes emotion identification as a transdiagnostic skill, relevant across anxiety, depression and personality disorders. Recent experimental work suggests that even brief online emotion-word learning tasks can enhance negative emotion differentiation and emotional self-efficacy (Matt, Seah & Coifman, 2024).

In practice, a client who distinguishes between “guilt” and “shame” may pursue different strategies. Guilt often motivates reparative action; shame may require self-compassion and cognitive restructuring. Identifying the difference changes the therapeutic pathway.

7.0 Applications in Education

Schools increasingly incorporate emotional literacy programmes. Rivers et al. (2012) demonstrated that structured emotional education improves classroom climate and students’ regulation skills. Teaching children to articulate feelings such as “nervous” before a presentation or “excluded” during group work promotes empathy and resilience.

Emotion labelling in performance contexts, such as music or sport, has also been shown to reduce anxiety and enhance performance quality (Kaleńska-Rodzaj, 2021). Recognising pre-performance nerves as “anticipatory excitement” rather than “fear” can alter physiological interpretation and outcome.

8.0 Why Identification Matters in Everyday Life

In daily life, emotions often operate beneath conscious awareness. When unidentified, they can manifest as irritability, withdrawal or somatic complaints. Naming the emotion creates cognitive space. It transforms a vague sense of unease into something definable and therefore actionable.

Importantly, identifying emotions fosters self-compassion. Rather than judging oneself for “being dramatic”, one might recognise feeling “hurt” or “rejected”. The shift from judgement to understanding supports psychological well-being.

The ability to identify emotions is not a trivial skill; it is a scientifically supported mechanism underpinning emotion regulation, psychological resilience, and healthy relationships. From neuroscience to psychotherapy to education, research converges on a simple yet profound insight: when we name our feelings, we gain power over them.

Developing emotional vocabulary—whether through tools like the Feel Wheel, reflective journalling or therapeutic guidance—cultivates emotional granularity and intelligence. In a world that often encourages suppression or distraction, the deliberate act of identifying emotions offers a direct pathway to clarity, balance and well-being.

References

Almheiri, N. (2021) Connecting Theories of Emotional Intelligence and Emotion Regulation with Positive Psychology. University of Pennsylvania.

Barrett, L.F. (2017) How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Beck, A.T. (2011) Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press.

Black, S.K. (2013) Affect Labeling as an Emotion Regulation Mechanism of Mindfulness in the Context of Cognitive Models of Depression. Temple University.

Bood, J.K. (2025) Impact of Emotional Intelligence Training on Burnout in Generation Z Business Students. ProQuest Dissertation.

Goleman, D. (1995) Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. London: Bantam Books.

Hofmann, S.G. (2015) Emotion in Therapy: From Science to Practice. New York: Guilford Press.

Kaleńska-Rodzaj, J. (2021) ‘Music performance anxiety and pre-performance emotions in the light of psychology of emotion and emotion regulation’, Psychology of Music, 49(6), pp. 1453–1468.

Kashdan, T.B., Barrett, L.F. and McKnight, P.E. (2015) ‘Unpacking emotion differentiation: Transforming unpleasant experience by perceiving distinctions in negativity’, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(1), pp. 10–16.

Leahy, R.L., Tirch, D. and Napolitano, L.A. (2011) Emotion Regulation in Psychotherapy: A Practitioner’s Guide. New York: Guilford Press.

Lieberman, M.D., Inagaki, T.K., Tabibnia, G. and Crockett, M.J. (2007) ‘Subjective responses to emotional stimuli during labeling, reappraisal, and distraction’, Emotion, 7(3), pp. 468–480.

Matt, L.M., Seah, T.H.S. and Coifman, K.G. (2024) ‘Effects of a brief online emotion word learning task on negative emotion differentiation and distress’, PLoS ONE, 19(3).

Nook, E.C. and Somerville, L.H. (2019) ‘Emotion concept development from childhood to adulthood’, in Emotion in the Mind and Body. Springer.

Rivers, S.E., Brackett, M.A., Katulak, N.A. and Salovey, P. (2012) ‘Regulating emotion in the classroom: The effectiveness of the RULER approach’, Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), pp. 649–657.

Vine, V. (2016) The Transdiagnostic, Context-sensitive Role of Emotion Identification in Emotion Regulation and Psychological Health. ProQuest Dissertation.

Zaki, L.F., Coifman, K.G., Rafaeli, E., Berenson, K.R. and Downey, G. (2013) ‘Emotion differentiation as a protective factor against nonsuicidal self-injury’, Behavior Therapy, 44(3), pp. 529–540.