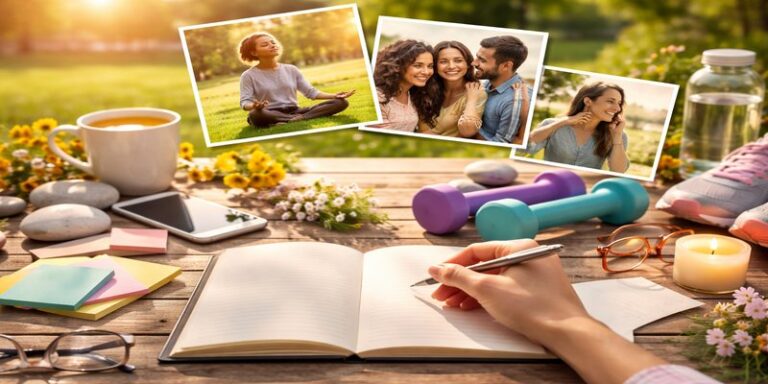

This article “How to Feel Better Instantly” presents a simple but powerful framework linking common emotional states (e.g. overthinking, stress, low energy) with practical actions (e.g. journalling, deep breathing, exercise). The advice provided in this article aligns closely with established psychological theory and empirical research. This article critically explores the scientific foundations behind these recommendations, drawing on textbooks, peer-reviewed journal articles and reputable health organisations, and demonstrates how small behavioural interventions can significantly improve wellbeing.

1.0 The Psychology of Immediate Emotional Regulation

Human emotions are shaped by the interaction between cognition, physiology and behaviour (Gross, 2015). According to cognitive-behavioural theory, thoughts influence feelings, and behaviours reinforce or alter emotional states (Beck, 2011). Therefore, changing behaviour—even briefly—can interrupt negative cognitive cycles.

The strategies presented in the image reflect principles of behavioural activation, mindfulness, and self-regulation theory. Behavioural activation, commonly used in the treatment of depression, posits that engaging in meaningful or rewarding activities reduces rumination and low mood (Martell, Dimidjian & Herman-Dunn, 2010). Similarly, self-regulation involves consciously modifying responses to align with goals and values (Baumeister & Vohs, 2007).

2.0 Overthinking and Journalling

The suggestion to “write in a journal” when overthinking is supported by research on expressive writing. Pennebaker and Chung (2011) found that structured writing about emotions reduces rumination and improves psychological health. Writing externalises internal worries, allowing individuals to process thoughts more rationally rather than cyclically.

For example, a university student anxious about exams may repeatedly replay worst-case scenarios. Writing these fears down often reveals cognitive distortions, such as catastrophising identified in Beck’s cognitive model (Beck, 2011). Journalling thus serves as a practical cognitive restructuring tool.

3.0 Anxiety and Deep Breathing

The image recommends “take 10 deep breaths” for anxiety. This reflects the role of the autonomic nervous system in emotional arousal. Anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system (“fight or flight”), increasing heart rate and muscle tension. Slow diaphragmatic breathing stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system, promoting calm (Jerath et al., 2015).

The NHS (2023) advises breathing exercises as a frontline strategy for managing mild anxiety. Empirical evidence shows controlled breathing reduces cortisol and physiological arousal (Ma et al., 2017). For example, individuals experiencing public-speaking anxiety can use paced breathing before presenting to reduce somatic symptoms.

4.0 Low Energy and Physical Activity

The recommendation to “go for a walk” when experiencing low energy aligns with extensive research on exercise and mood. Contrary to intuition, physical activity often increases perceived energy. According to the World Health Organization (2022), moderate exercise improves mood and reduces fatigue.

Neurobiologically, exercise increases endorphins, dopamine, and serotonin, neurotransmitters associated with positive affect (Ratey & Loehr, 2011). A short walk outdoors can also enhance attention and restore mental energy, consistent with Attention Restoration Theory (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989).

For instance, office workers reporting afternoon fatigue frequently experience improved concentration after a 15-minute walk.

5.0 Stress and Social Connection

Calling a loved one or connecting with a friend reflects the protective role of social support. Social connectedness is one of the strongest predictors of wellbeing (Diener & Seligman, 2002). Cohen and Wills (1985) demonstrated that social support buffers against stress by altering cognitive appraisal.

From a biological perspective, positive social interaction increases oxytocin, which reduces stress responses (Heinrichs et al., 2003). For example, discussing workplace pressures with a supportive partner can reduce perceived burden and enhance coping capacity.

6.0 Procrastination and Reducing Distraction

The advice to “put your phone away” when procrastinating reflects principles of self-control and attentional management. Baumeister and Tierney (2011) argue that reducing environmental temptations strengthens goal-directed behaviour.

Research shows digital interruptions fragment attention and increase task-switching costs (Rosen et al., 2013). Removing the phone reduces cognitive load and enhances focus. This strategy exemplifies environmental modification, a key behavioural intervention in habit formation (Wood & Neal, 2007).

7.0 Feeling Lost and Goal Setting

Writing down goals is consistent with goal-setting theory, which posits that specific, challenging goals enhance motivation and performance (Locke & Latham, 2002). Goals provide structure, direction and a sense of agency.

For example, an individual feeling uncertain about career direction may regain clarity by identifying short-term actionable objectives. Research indicates that written goals are more likely to be achieved due to enhanced commitment and monitoring (Locke & Latham, 2002).

8.0 Guilt and Self-Compassion

The suggestion to “forgive yourself” reflects emerging research on self-compassion. Neff (2003) defines self-compassion as treating oneself with kindness during failure. Studies link self-compassion with lower anxiety, depression and shame (Neff & Germer, 2013).

Self-forgiveness does not eliminate responsibility but reduces maladaptive rumination. For example, an employee who makes a mistake may experience guilt; practising self-compassion promotes learning rather than self-punishment.

9.0 Impatience and Meditation

The advice to “meditate for 5 minutes” reflects evidence supporting mindfulness-based interventions. Mindfulness cultivates non-judgemental awareness of the present moment (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Even brief sessions improve emotional regulation and reduce impulsivity (Zeidan et al., 2010).

Meditation strengthens the prefrontal cortex, enhancing executive control over emotional responses (Hölzel et al., 2011). In practical terms, a short mindfulness pause before responding in conflict can prevent reactive behaviour.

10.0 Disconnection and Volunteering

Volunteering addresses feelings of disconnection by fostering purpose and belonging. Research indicates that prosocial behaviour increases life satisfaction and reduces depressive symptoms (Thoits & Hewitt, 2001). Helping others enhances meaning—a core component of wellbeing in positive psychology (Seligman, 2011).

For example, volunteering at a local charity may strengthen community ties and identity, counteracting loneliness.

11.0 Insecurity and Listing Achievements

Listing achievements promotes self-efficacy, defined as belief in one’s ability to succeed (Bandura, 1997). Reflecting on past successes enhances confidence and motivation. According to self-efficacy theory, mastery experiences are the strongest source of confidence (Bandura, 1997).

A student preparing for an interview may reduce insecurity by reviewing prior accomplishments, thereby activating a positive self-schema.

Below is a comparative table linking the emotional states shown in the image with the recommended actions and their psychological mechanisms, supported by theory and research.

Comparative Table: Emotional States and Evidence-Based Interventions

| Feeling / Emotional State | Recommended Action | Practical Example |

| Overthinking | Write in a journal | Writing exam worries to identify cognitive distortions |

| Anxious | Take 10 deep breaths | Deep breathing before public speaking |

| Low energy | Go for a walk | 15-minute outdoor walk during work break |

| Stressed | Call a loved one | Discussing workload with a supportive partner |

| Procrastinating | Put your phone away | Removing phone during focused study session |

| Overwhelmed | Connect with a friend | Meeting a friend for reassurance and clarity |

| Feeling lost | Write down your goals | Setting short-term career objectives |

| Unmotivated | Go to the gym | Strength training to increase energy and drive |

| Guilty | Forgive yourself | Reflecting kindly after making a mistake |

| Impatient | Meditate for 5 minutes | Short breathing meditation before responding in conflict |

| Disconnected | Volunteer for a cause | Volunteering at a community centre |

| Insecure | List your achievements | Reviewing past accomplishments before interview |

These recommendations are grounded in robust psychological science. They draw upon cognitive-behavioural principles, physiological regulation, social psychology, and positive psychology. The key insight is that small, intentional behavioural changes can rapidly influence emotional states. By targeting cognition (journalling), physiology (breathing), behaviour (exercise), environment (reducing distraction), and social connection (calling a loved one), individuals can meaningfully improve wellbeing.

Such strategies are not substitutes for professional mental health care in severe cases; however, as evidence-based micro-interventions, they represent accessible tools for everyday emotional regulation.

References

Bandura, A. (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Baumeister, R.F. and Vohs, K.D. (2007) ‘Self-regulation, ego depletion, and motivation’, Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), pp. 115–128.

Baumeister, R.F. and Tierney, J. (2011) Willpower. New York: Penguin.

Beck, J.S. (2011) Cognitive behaviour therapy: Basics and beyond. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press.

Cohen, S. and Wills, T.A. (1985) ‘Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis’, Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), pp. 310–357.

Diener, E. and Seligman, M.E.P. (2002) ‘Very happy people’, Psychological Science, 13(1), pp. 81–84.

Gross, J.J. (2015) ‘Emotion regulation’, Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), pp. 1–26.

Heinrichs, M. et al. (2003) ‘Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol’, Biological Psychiatry, 54(12), pp. 1389–1398.

Hölzel, B.K. et al. (2011) ‘Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain grey matter density’, Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 191(1), pp. 36–43.

Jerath, R. et al. (2015) ‘Physiology of long pranayamic breathing’, Medical Hypotheses, 85(5), pp. 486–496.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003) ‘Mindfulness-based interventions in context’, Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), pp. 144–156.

Locke, E.A. and Latham, G.P. (2002) ‘Building a practically useful theory of goal setting’, American Psychologist, 57(9), pp. 705–717.

Ma, X. et al. (2017) ‘The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention’, Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 874.

Martell, C.R., Dimidjian, S. and Herman-Dunn, R. (2010) Behavioural activation for depression. New York: Guilford Press.

Neff, K.D. (2003) ‘Self-compassion’, Self and Identity, 2(2), pp. 85–101.

Neff, K.D. and Germer, C.K. (2013) ‘A pilot study of mindful self-compassion’, Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), pp. 28–44.

NHS (2023) Self-help for stress and anxiety. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk (Accessed: 13 February 2026).

Ratey, J.J. and Loehr, J.E. (2011) ‘The positive impact of physical activity on cognition’, Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(10), pp. 1253–1258.

Seligman, M.E.P. (2011) Flourish. New York: Free Press.

Thoits, P.A. and Hewitt, L.N. (2001) ‘Volunteer work and well-being’, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(2), pp. 115–131.

Wood, W. and Neal, D.T. (2007) ‘A new look at habits’, Psychological Review, 114(4), pp. 843–863.

World Health Organization (2022) Physical activity. Available at: https://www.who.int (Accessed: 13 February 2026).

Zeidan, F. et al. (2010) ‘Mindfulness meditation improves cognition’, Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), pp. 597–605.