The history of Roman Britain represents a decisive chapter in the development of the British Isles. Between 43 and 410 CE, Britain formed part of the Roman Empire, undergoing profound transformations in governance, economy, infrastructure and culture. Roman rule did not simply impose foreign control; it integrated Britain into a vast imperial network stretching from North Africa to the Near East. Historians increasingly emphasise that Roman Britain was shaped by processes of military conquest, urbanisation, economic integration and cultural exchange, rather than by simple domination (Mattingly, 2006; Millett, 1990). This article explores the political, social and cultural evolution of Roman Britain within its wider imperial context.

1.0 The Roman Conquest of Britain

Although Julius Caesar conducted expeditions to Britain in 55 and 54 BCE, lasting occupation did not begin until 43 CE, when Emperor Claudius ordered a full-scale invasion. According to Tacitus (trans. 2009), the conquest was motivated partly by prestige and partly by economic ambition, including access to Britain’s mineral resources.

Roman forces gradually subdued much of southern Britain, establishing military bases and colonies. However, resistance remained strong. The revolt of Boudicca, queen of the Iceni, in 60–61 CE, nearly expelled Roman forces from the province. Her uprising demonstrates that conquest was neither immediate nor uncontested (Mattingly, 2006).

By the late first century, Roman authority extended across much of England and Wales. Scotland, however, remained only partially controlled. The construction of Hadrian’s Wall (122 CE) under Emperor Hadrian marked a strategic decision to consolidate rather than expand imperial boundaries.

2.0 Provincial Administration and Governance

Roman Britain became a formal province governed by a Roman governor, supported by military and administrative officials. The province was later divided into smaller units to enhance efficiency and control. As Millett (1990) argues, Roman provincial governance relied on cooperation with local elites, who were incorporated into Roman administrative structures.

Roman law, taxation and civic administration were introduced, reshaping political organisation. Indigenous tribal leaders often retained local influence but operated within a Roman framework. This process illustrates what scholars term “Romanisation”, although recent historiography questions whether this concept implies too one-sided a cultural transformation (Woolf, 1998).

3.0 Urbanisation and Infrastructure

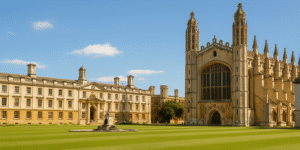

One of the most visible legacies of Roman Britain was the development of urban centres. Towns such as Londinium (London), Verulamium (St Albans) and Eboracum (York) became administrative and commercial hubs. These settlements featured forums, bathhouses, amphitheatres and temples, reflecting Roman architectural styles.

The construction of extensive road networks facilitated military movement and economic exchange. Roman engineering introduced stone bridges, aqueducts and fortified settlements. According to Mattingly (2006), such infrastructure integrated Britain more closely into imperial trade systems.

Urbanisation did not replace rural life entirely; most Britons continued to live in agricultural communities. However, the emergence of villa estates suggests increasing economic stratification and elite adoption of Roman lifestyles.

4.0 Economy and Trade

Roman Britain became economically significant within the empire. The province exported grain, metals (particularly tin and lead), wool and slaves. In return, it imported wine, olive oil and luxury goods from across the Mediterranean.

Archaeological evidence reveals widespread use of Roman coinage, indicating monetisation of the economy. Trade networks connected Britain to Gaul, Spain and beyond. Millett (1990) argues that economic integration fostered both opportunity and dependency, embedding Britain within imperial supply chains.

5.0 Religion and Cultural Change

Roman Britain experienced significant religious transformation. Initially, indigenous Celtic religious practices continued alongside Roman polytheism. Temples dedicated to deities such as Mars and Jupiter appeared, sometimes combined with local gods in syncretic forms.

From the third century onwards, Christianity began to spread within Britain. Evidence of early Christian communities suggests that the province participated in wider religious developments within the empire. By the early fourth century, Christianity had gained imperial recognition following Constantine’s conversion.

Cultural change extended beyond religion. Latin became the language of administration, and Roman artistic styles influenced material culture. Yet, as Woolf (1998) emphasises, cultural exchange was reciprocal rather than purely imposed.

6.0 Military Presence and Frontier Defence

Britain remained a heavily militarised province. Legions were stationed at strategic locations, including York and Chester. The northern frontier was fortified by Hadrian’s Wall, later supplemented by the Antonine Wall in Scotland.

The military presence stimulated local economies but also underscored the province’s strategic vulnerability. Roman Britain functioned as both frontier and gateway, protecting the empire from northern incursions.

7.0 Decline and Withdrawal

By the late fourth century, Roman Britain faced increasing pressure from external threats and internal instability. The empire’s resources were stretched by invasions across Europe. In 410 CE, Emperor Honorius reportedly instructed British cities to look to their own defence (Mattingly, 2006).

The Roman withdrawal did not produce immediate collapse but initiated a gradual transformation. Urban centres declined, and political authority fragmented. The subsequent arrival of Anglo-Saxon groups marked a new historical phase.

8.0 Historiographical Debates

The interpretation of Roman Britain has evolved significantly. Earlier historians viewed Roman rule as a civilising force that brought progress to a primitive land. Modern scholars adopt a more critical perspective, emphasising imperial exploitation, military coercion and uneven cultural integration (Mattingly, 2006).

The concept of Romanisation has been particularly debated. Millett (1990) saw it as a process of elite adoption of Roman culture, while Woolf (1998) argues for a more complex understanding of identity and hybridity.

These debates highlight that Roman Britain was not merely a passive recipient of imperial influence but an active participant in cultural negotiation.

9.0 Legacy of Roman Britain

The legacy of Roman Britain is visible in:

- The foundations of London and other cities

- Road networks that influenced later infrastructure

- Legal and administrative traditions

- Early Christian communities

Although direct political continuity ended in 410 CE, the memory and material remains of Rome shaped later medieval and early modern interpretations of British identity.

Roman Britain represents a transformative period characterised by conquest, integration and cultural interaction. From Claudius’ invasion in 43 CE to the withdrawal in 410 CE, Britain was embedded within one of the most powerful empires in history. Roman rule introduced urbanisation, administrative governance, economic integration and religious change.

Modern scholarship demonstrates that Roman Britain cannot be reduced to a simple narrative of domination or civilisation. Instead, it was a dynamic province shaped by negotiation between imperial authority and local society. Its legacy endures in Britain’s urban foundations, infrastructure and historical consciousness.

References

Mattingly, D. (2006) An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire. London: Penguin.

Millett, M. (1990) The Romanization of Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tacitus (2009) Agricola and Germania. Translated by A. Goldsworthy. London: Penguin Classics.

Woolf, G. (1998) Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.