The Renaissance was a transformative period in European history that marked a profound cultural, artistic, and intellectual awakening following the Middle Ages. Originating in Italy during the 14th century, the movement gradually spread across Europe, profoundly influencing art, literature, science, and philosophy. It was characterised by a renewed interest in classical antiquity, the emergence of humanism, and the rise of individualism and scientific inquiry (Burke, 1998). The term “Renaissance,” meaning “rebirth,” reflects the revival of Greco-Roman ideals that sought to re-establish the dignity and potential of humankind. This essay explores the origins, philosophical foundations, artistic innovations, and enduring legacy of the Renaissance, drawing upon scholarly sources and historical examples.

Origins and Historical Context

The Renaissance began in northern Italian city-states such as Florence, Venice, and Milan, between the 14th and 16th centuries, a period of significant economic and political transformation. Florence, in particular, became a hub of artistic and intellectual activity under the patronage of powerful families such as the Medici, whose wealth derived from banking and commerce (Welch, 2011). The collapse of feudalism and the rise of urban mercantile classes created an environment conducive to new ideas and cultural experimentation.

According to Burke (1998), the rediscovery of classical texts by scholars such as Petrarch (1304–1374) and Boccaccio (1313–1375) played a crucial role in shaping Renaissance thought. These humanists sought to recover and reinterpret the works of Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero, promoting a worldview that placed humanity—not divine authority—at the centre of intellectual inquiry. As Kristeller (1961) asserts, humanism was the intellectual backbone of the Renaissance, advocating the study of humanities—grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy—as the means to cultivate virtue and civic responsibility.

The Philosophy of Humanism

At the heart of the Renaissance lay humanism, a philosophical and cultural movement that celebrated the dignity, freedom, and potential of the individual. Humanists rejected the medieval scholastic focus on theological dogma, instead emphasising rationality, empirical observation, and self-expression. According to Nauert (2006), Renaissance humanism did not dismiss religion but sought to reconcile Christian faith with classical learning, a synthesis evident in the writings of figures such as Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466–1536) and Thomas More (1478–1535).

Erasmus’s In Praise of Folly (1509) satirised ecclesiastical corruption while promoting a return to simple Christian piety grounded in reason. Similarly, More’s Utopia (1516) explored ideals of social justice and moral virtue through classical-inspired political thought. These works illustrate how humanism encouraged critical reflection on society, morality, and governance.

Humanism’s emphasis on education also transformed intellectual life. Institutions began to adopt the studia humanitatis, or the “study of humanity,” fostering broader access to learning beyond the clergy (Black, 2001). This educational reform laid the foundations for modern liberal education and intellectual freedom.

Artistic Innovation and the Revival of Classical Ideals

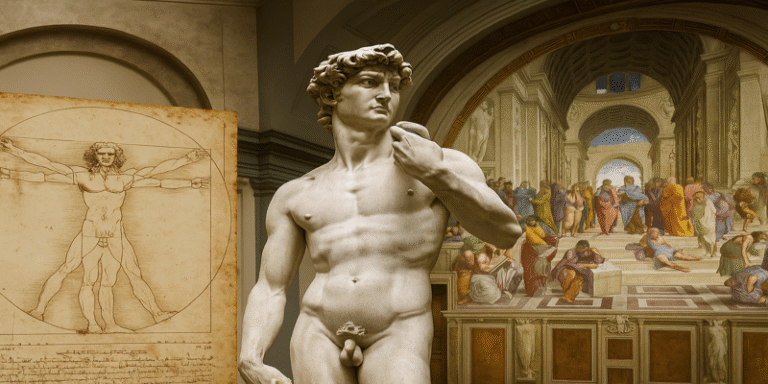

The visual arts of the Renaissance exemplified its intellectual and aesthetic ideals. Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, and Raphael Sanzio revolutionised artistic practice by combining technical mastery with philosophical depth. They viewed art as a form of intellectual pursuit, grounded in mathematics, geometry, and anatomical study.

Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man (c.1490) epitomises the Renaissance ideal of the “universal man”, illustrating the harmony between the human body and the cosmos through geometric proportion (Kemp, 2006). His integration of art and science reflected a belief that artistic creation mirrored divine order and rationality. Similarly, Michelangelo’s David (1501–1504) embodies both classical heroism and humanist confidence, portraying man as a noble, self-determining being capable of moral greatness (Hauser, 2005).

The development of linear perspective, pioneered by Filippo Brunelleschi and theorised by Leon Battista Alberti in De Pictura (1435), revolutionised visual representation by enabling artists to depict three-dimensional space on a flat surface with mathematical precision (Edgerton, 2009). This innovation marked a departure from the two-dimensional stylisation of medieval art, reflecting a new understanding of vision, space, and perception.

Moreover, artists drew inspiration from classical sculpture and architecture, reviving ancient motifs and proportions. The façades of Brunelleschi’s churches and Alberti’s palaces demonstrate a harmony of symmetry, balance, and proportion—principles derived from Roman and Greek models (Wittkower, 1999).

The Scientific Renaissance

Parallel to artistic achievements, the Renaissance was marked by a scientific revolution that transformed understanding of the natural world. Scholars began to challenge traditional authorities, adopting empirical observation and rational analysis as the basis of knowledge. According to Lindberg (2007), this shift was influenced by both humanist inquiry and the revival of classical scientific texts, notably those of Ptolemy, Galen, and Archimedes.

Figures such as Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, and Andreas Vesalius made groundbreaking discoveries that questioned established doctrines. Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543) proposed a heliocentric model of the universe, challenging the long-standing geocentric system endorsed by the Church. Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica (1543) revolutionised the study of human anatomy through direct dissection and observation, illustrating the Renaissance commitment to empirical truth (Lindberg, 2007).

These developments laid the intellectual foundations for the later Scientific Revolution of the 17th century, exemplifying how Renaissance thought fostered the spirit of inquiry that continues to define modern science.

The Spread and Legacy of the Renaissance

While the Renaissance began in Italy, its ideas spread across Europe through printing technology, trade, and cultural exchange. The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440 revolutionised the dissemination of knowledge, enabling rapid circulation of texts and ideas (Eisenstein, 1983).

In Northern Europe, the Renaissance took on a more religious and moral character, with artists like Albrecht Dürer and Jan van Eyck combining humanist ideals with Christian devotion. The Northern Renaissance also fostered social and political reflection, influencing the Protestant Reformation and subsequent shifts in European thought.

The Renaissance’s legacy endures in modern conceptions of individualism, rationality, and aesthetic expression. As Burke (1998) notes, the movement reshaped Western civilisation by redefining humanity’s place in the cosmos, celebrating intellectual freedom and creative achievement as expressions of divine potential.

Moreover, its influence extended beyond art and science to politics, literature, and philosophy, laying the groundwork for the Enlightenment. The enduring appeal of Renaissance ideals—reason, beauty, and human dignity—continues to inform contemporary culture, education, and the arts.

The Renaissance represented a turning point in human history, characterised by the revival of classical ideals, the rise of humanism, and the pursuit of knowledge through observation and reason. From the architectural symmetry of Brunelleschi to the anatomical precision of Leonardo, and from the philosophical insights of Erasmus to the astronomical discoveries of Copernicus, the Renaissance redefined what it meant to be human.

This rebirth of learning and creativity bridged the medieval and modern worlds, transforming European society’s intellectual, artistic, and moral outlook. Ultimately, the Renaissance’s most enduring legacy lies in its celebration of the human mind’s limitless capacity for understanding, invention, and beauty.

References

Black, R. (2001) Humanism and Education in Medieval and Renaissance Italy: Tradition and Innovation in Latin Schools from the Twelfth to the Fifteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burke, P. (1998) The European Renaissance: Centres and Peripheries. Oxford: Blackwell.

Edgerton, S.Y. (2009) The Mirror, the Window, and the Telescope: How Renaissance Linear Perspective Changed Our Vision of the Universe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Eisenstein, E.L. (1983) The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hauser, A. (2005) The Social History of Art: Volume 2 – Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque. London: Routledge.

Kemp, M. (2006) Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kristeller, P.O. (1961) Renaissance Thought: The Classic, Scholastic, and Humanist Strains. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Lindberg, D.C. (2007) The Beginnings of Western Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nauert, C.G. (2006) Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Welch, E. (2011) Art and Society in Italy, 1350–1500. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wittkower, R. (1999) Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism. London: Academy Editions.