In an age of information overload and competing narratives, the ability to engage in critical thinking has never been more vital. Whether in higher education, professional settings, or personal decision-making, the capacity to analyse, evaluate, and synthesise information objectively underpins effective problem-solving and sound judgement. According to the Chartered Management Institute (CMI), critical thinking is defined as a “disciplined process” involving reflective, reasonable, and rational thinking used to evaluate the authenticity, accuracy, and worth of knowledge claims (CMI, n.d.).

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking goes beyond passive absorption of facts. It entails questioning assumptions, considering multiple perspectives, and arriving at well-supported conclusions. As Facione (2011) outlines, critical thinking includes skills such as interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, and explanation. These are not isolated mental tasks but interwoven aspects of a broader cognitive discipline that allows individuals to engage with content in a nuanced and meaningful way.

Furthermore, the CMI (n.d.) notes that critical thinkers must also be open-minded and sceptical—ready to challenge their own beliefs while remaining receptive to evidence-based counterarguments. This balance between scepticism and open-mindedness is essential in distinguishing critical thinking from cynicism or mere disagreement.

Applications in Higher Education

In universities, critical thinking is a cornerstone of academic success. Students are expected not only to understand and recall information but to analyse arguments, evaluate sources, and develop original insights. According to Moon (2008), fostering critical thinking in students allows them to “learn how to learn” and engage with knowledge as active participants rather than passive recipients.

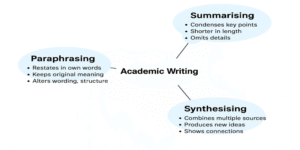

For instance, when writing a literature review, students must assess the reliability of sources, identify biases, compare methodologies, and determine the validity of findings. This analytical approach prevents the uncritical reproduction of dominant views and encourages academic independence.

Additionally, Brookfield (2012) asserts that critical thinking in education should involve confronting one’s own assumptions and recognising the cultural and contextual influences on belief systems. For example, a sociology student examining gender roles must be aware of how societal norms, media, and personal upbringing shape their understanding of the issue.

Importance in Professional Settings

Beyond academia, critical thinking is equally essential in the workplace. In management, for example, leaders must make decisions that involve evaluating conflicting data, assessing risks, and forecasting outcomes. According to Paul and Elder (2014), professionals who exhibit strong critical thinking skills tend to be better at solving complex problems and navigating uncertainty.

Consider a marketing executive faced with declining sales. Instead of impulsively altering the product or increasing the budget, a critical thinker would analyse consumer behaviour data, evaluate competitor strategies, and test hypotheses through market research. This methodical approach can save resources and lead to more sustainable outcomes.

Similarly, in healthcare, clinical reasoning—a form of critical thinking—helps practitioners make informed decisions that can have life-or-death consequences. Benner et al. (2009) emphasise that clinical judgment depends heavily on the ability to analyse patient data, weigh alternative diagnoses, and reflect on past cases.

Evaluating Sources of Information

In both academic and real-world settings, evaluating sources is a key element of critical thinking. The CMI (n.d.) highlights the importance of scrutinising the credibility, bias, and recency of information. In today’s digital environment, where misinformation proliferates, this skill is especially critical.

A valuable framework for source evaluation is the CRAAP test, which stands for Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose (Blakeslee, 2004). This tool enables students and professionals alike to assess whether a source is trustworthy and suitable for their needs.

For example, a business student citing economic data must ensure the statistics are from a reputable source such as the Office for National Statistics (ONS) or World Bank, and not from a blog or outdated report. Likewise, a journalist verifying claims about climate change should reference peer-reviewed studies from journals like Nature or Environmental Research Letters.

Identifying and Challenging Assumptions

One of the hallmarks of critical thinking is the ability to identify and challenge assumptions. This skill prevents individuals from accepting ideas at face value and encourages them to explore alternative explanations.

For instance, in public policy discussions about crime, one might assume that harsher penalties reduce offending rates. However, critical examination of criminological research reveals that deterrence theory is contested, and factors such as education, social support, and rehabilitation may be more effective (Tonry, 2019). By questioning assumptions, critical thinkers contribute to more nuanced and evidence-informed debates.

Avoiding Logical Fallacies

Critical thinkers must also recognise and avoid logical fallacies—errors in reasoning that undermine the validity of an argument. The CMI (n.d.) stresses that inductive and deductive reasoning must be free from fallacies such as straw man, false dichotomy, or ad hominem attacks.

For example, in political discourse, it is common to encounter appeals to emotion rather than reasoned argument. A politician claiming, “Anyone who doesn’t support this policy doesn’t care about the country,” is engaging in a false dilemma, presenting only two options when multiple perspectives exist.

Cultivating Reflective Skepticism

Another essential component is reflective scepticism—the willingness to question both external information and one’s internal beliefs. As Ennis (2011) describes, this requires cultivating intellectual humility and resisting cognitive biases.

The concept of confirmation bias, where individuals seek information that aligns with their beliefs while ignoring contradictory evidence, is particularly relevant. By recognising this tendency, critical thinkers can strive for greater objectivity and balance in their assessments.

In summary, critical thinking is an indispensable skill in education, the workplace, and civic life. It empowers individuals to navigate complexity, evaluate arguments, and make informed decisions. As the CMI outlines, critical thinking is not about negativity or consensus but about reasoned judgment, evidence-based reasoning, and intellectual integrity.

To develop this skill, individuals must cultivate habits of open-mindedness, questioning, source evaluation, and logical analysis. In doing so, they not only enhance their personal effectiveness but also contribute to more thoughtful, democratic, and informed societies.

References

Benner, P., Tanner, C. A., & Chesla, C. A. (2009). Expertise in nursing practice: Caring, clinical judgment, and ethics. Springer Publishing Company.

Blakeslee, S. (2004). The CRAAP test. LOEX Quarterly, 31(3), 6-7.

Brookfield, S. D. (2012). Teaching for critical thinking: Tools and techniques to help students question their assumptions. Jossey-Bass.

Chartered Management Institute (CMI). (n.d.). Critical Thinking.

Ennis, R. H. (2011). The nature of critical thinking: An outline of critical thinking dispositions and abilities. University of Illinois.

Facione, P. A. (2011). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Insight Assessment.

Moon, J. (2008). Critical thinking: An exploration of theory and practice. Routledge.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2014). The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools. Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

Tonry, M. (2019). Punishment and crime across space and time. Oxford University Press.