The idea that one year can transform a life is not merely motivational rhetoric; it is supported by research in positive psychology, behavioural science, health psychology, and cognitive theory. Sustainable change does not occur through sudden inspiration but through consistent behavioural shifts grounded in evidence-based principles. This article critically explores eight life-changing practices—gratitude, constructive solitude, relationship boundaries, digital discipline, skill development, goal commitment, exercise, and learning from failure—through the lens of scientific research.

1.0 Stop Complaining and Practise Gratitude

Shifting from habitual complaining to gratitude practice has measurable psychological benefits. Gratitude interventions have been associated with improved mood, optimism, and life satisfaction (Emmons and McCullough, 2003). Rather than denying challenges, gratitude involves consciously recognising positive aspects of daily life.

For example, individuals who write down three things they are thankful for each evening report improved wellbeing over time. According to Seligman (2011), gratitude strengthens positive emotion, one of the five pillars of flourishing in the PERMA model.

Moreover, chronic complaining may reinforce negative cognitive biases, whereas gratitude retrains attentional focus. In cognitive behavioural terms, this represents a shift in cognitive appraisal (Beck, 2011).

2.0 Embrace Loneliness and Reinvent Yourself

Solitude, when chosen rather than imposed, can facilitate self-reflection and identity development. Developmental psychology suggests that periods of introspection are essential for personal growth (Erikson, 1968).

Constructive solitude allows individuals to reassess values, career paths, and relationships. For instance, someone experiencing a transitional period—such as moving cities—may use that time to develop new routines, hobbies, or goals.

However, it is important to distinguish solitude from social isolation. Research shows that prolonged unwanted loneliness negatively affects health (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). The transformative potential lies in intentional self-renewal, not chronic withdrawal.

3.0 Say Goodbye to Negative Influences

Social networks strongly influence behaviour. Social learning theory (Bandura, 1997) demonstrates that individuals adopt habits observed in peers. Surrounding oneself with supportive, goal-oriented individuals increases the likelihood of success.

For example, an individual trying to reduce alcohol consumption may struggle if their primary social circle normalises heavy drinking. Conversely, joining a health-focused group reinforces constructive behaviour.

Holt-Lunstad et al. (2010) found that strong, positive social relationships significantly reduce mortality risk. Quality, not quantity, of relationships is crucial.

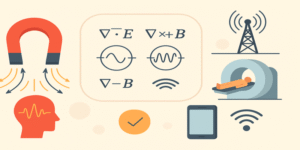

4.0 Reduce Excessive Media Consumption

Excessive television and internet use are associated with sedentary behaviour, sleep disruption, and reduced productivity. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2023) identifies physical inactivity as a major global health risk.

Additionally, excessive digital consumption may impair attention span and increase anxiety (Taylor, 2021). Setting structured boundaries—such as limiting screen time in the evening—can improve sleep hygiene and mental clarity.

For example, replacing one hour of evening scrolling with reading or skill development may compound benefits over a year.

5.0 Develop One Skill Intensively

Focusing deeply on one meaningful skill reflects the principle of deliberate practice, described by Ericsson, Krampe and Tesch-Römer (1993). Expertise develops through sustained, focused effort rather than scattered attempts.

Whether learning a language, mastering public speaking, or developing coding skills, consistent daily practice over 12 months produces measurable progress.

Moreover, building competence enhances self-efficacy, defined as belief in one’s ability to succeed (Bandura, 1997). Self-efficacy predicts resilience, persistence, and achievement.

6.0 Commit to Clear Goals

Goal-setting theory demonstrates that specific and challenging goals enhance performance (Locke and Latham, 2002). Vague aspirations such as “be healthier” are less effective than measurable objectives such as “exercise four times weekly”.

Commitment involves persistence despite setbacks. Research shows that written goals increase accountability and achievement likelihood.

For example, committing to saving a specific amount monthly can significantly improve financial stability within one year.

7.0 Exercise Daily to Improve Mood

Regular physical activity is one of the most evidence-based strategies for improving both physical and mental health. Exercise reduces symptoms of depression and anxiety and enhances cognitive functioning (Taylor, 2021).

Physiologically, exercise increases endorphins, serotonin, and dopamine—neurochemicals associated with mood regulation.

The WHO (2023) recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity weekly. Even brisk walking or cycling can significantly enhance wellbeing.

Importantly, exercise also strengthens discipline and routine, reinforcing other positive behaviours.

8.0 Fail Forward and Learn from Mistakes

Viewing failure as feedback rather than defeat aligns with the concept of a growth mindset (Dweck, 2006). Individuals who perceive abilities as malleable are more likely to persist after setbacks.

For example, an entrepreneur whose first business venture fails may analyse mistakes and apply lessons to future attempts. Over time, iterative learning increases competence.

Psychological resilience involves adaptive coping strategies in the face of adversity (Marks et al., 2024). Failure becomes a catalyst for refinement rather than a source of stagnation.

The Compound Effect of Behavioural Change

While each of these practices individually contributes to growth, their combined impact creates a compound effect. Behavioural science suggests that small, consistent actions accumulate over time to produce substantial transformation.

For example:

- Daily gratitude reshapes cognitive focus.

- Weekly exercise enhances energy and mood.

- Monthly skill development builds competence.

- Continuous goal commitment strengthens discipline.

Over twelve months, these incremental adjustments reshape identity, habits, and social networks.

Critical Reflection: Is Change Guaranteed?

Personal transformation is influenced by contextual factors such as socioeconomic status, health conditions, and environmental constraints. Health psychology recognises that behaviour change depends on motivation, opportunity, and support systems (Taylor, 2021).

Nevertheless, individuals retain significant agency in shaping habits. Sustainable change relies on realistic expectations and incremental improvement rather than dramatic overnight transformation.

Transforming one’s life within a year is possible through consistent application of evidence-based behavioural principles. By cultivating gratitude, constructive solitude, supportive relationships, digital discipline, skill mastery, goal commitment, physical activity, and resilience in failure, individuals can substantially improve wellbeing and achievement.

Change does not require perfection; it requires persistence. Through small, daily actions aligned with long-term values, the trajectory of a year—and indeed a lifetime—can shift profoundly.

References

Bandura, A. (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Beck, J.S. (2011) Cognitive behaviour therapy: Basics and beyond. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press.

Dweck, C.S. (2006) Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

Emmons, R.A. and McCullough, M.E. (2003) ‘Counting blessings versus burdens’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), pp. 377–389.

Erikson, E.H. (1968) Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Ericsson, K.A., Krampe, R.T. and Tesch-Römer, C. (1993) ‘The role of deliberate practice’, Psychological Review, 100(3), pp. 363–406.

Holt-Lunstad, J. et al. (2010) ‘Social relationships and mortality risk’, PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

Locke, E.A. and Latham, G.P. (2002) ‘Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation’, American Psychologist, 57(9), pp. 705–717.

Marks, D.F., Murray, M., Locke, A. and Annunziato, R.A. (2024) Health psychology: Theory, research and practice. London: Sage.

Taylor, S.E. (2021) Health psychology. 11th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

World Health Organization (2023) Physical activity guidelines. Available at: https://www.who.int.