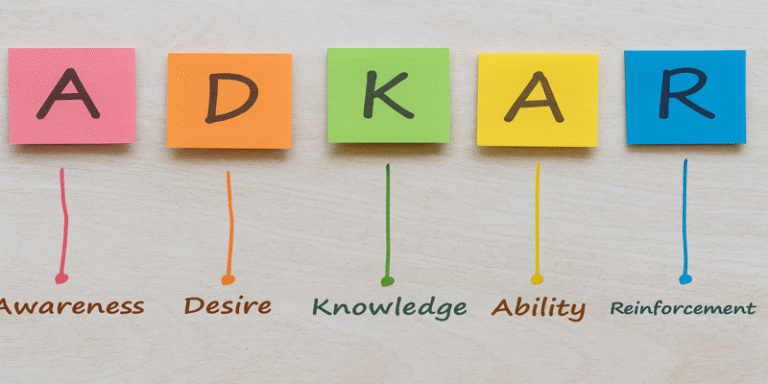

In today’s dynamic organisational landscape, effective change management remains a central challenge for leaders. Traditional models such as Lewin’s unfreeze–change–refreeze and Kotter’s 8-Step Process primarily emphasise organisational structures and leadership actions. However, Jeff Hiatt (2006) introduced the ADKAR model, which shifts the focus from organisational systems to the individual’s experience of change. This model proposes that transformation only succeeds when individuals transition effectively through five stages: Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement (Hiatt & Creasey, 2012).

This article critically explores the ADKAR model, highlighting its practical applications, strengths, and limitations. Contemporary examples from healthcare, higher education, and IT system rollouts illustrate its relevance, while scholarly perspectives examine its enduring contribution to change management theory and practice.

1.0 Awareness of the Need for Change

The first stage of ADKAR emphasises the necessity of creating awareness of why change is required. Without understanding the rationale, employees are likely to resist (Hiatt, 2006). Awareness is built through transparent communication and linking change to organisational survival or improvement.

For example, in healthcare settings, Hopkinson (2024) reported that applying ADKAR principles to continuous glucose monitoring adoption helped clinicians understand the urgency of technological change in improving patient safety. Similarly, in IT rollouts, awareness campaigns clarify how new systems enhance efficiency, reducing scepticism among staff (Hiatt & Creasey, 2012).

Creating awareness ensures employees are not only informed but also convinced that change is necessary, laying the foundation for subsequent adoption.

2.0 Desire to Support the Change

Awareness alone is insufficient; individuals must develop desire to engage with and support the change. This stage acknowledges the emotional dimension of transformation. Leaders must connect change initiatives to personal motivators such as career growth, recognition, or alignment with values.

Memana (2025) highlighted that ADKAR aligns with ethical and participatory approaches, which enhance employee motivation by fostering inclusivity and respect. In higher education, case studies show that when faculty perceive change as supporting student success and institutional reputation, they are more likely to commit actively (Kezar & Eckel, 2002).

By addressing intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, the desire stage transforms passive awareness into active commitment.

3.0 Knowledge of How to Change

Even motivated employees cannot change without the knowledge of what to do differently. The third stage involves providing training, resources, and guidance to ensure employees understand processes, systems, and skills required.

For example, in enterprise resource planning (ERP) rollouts, organisations often fail when employees lack knowledge of system functionalities (Somers & Nelson, 2001). ADKAR addresses this gap by emphasising structured training programmes tailored to diverse learning styles.

In academic contexts, knowledge-building occurs through workshops and peer learning, enabling cultural transformations such as inclusive teaching practices (Kezar, 2014). Knowledge provision bridges the gap between motivation and action.

4.0 Ability to Implement Behaviours

While knowledge is critical, employees must also possess the ability to apply it in practice. This stage recognises that capability requires experience, resources, and feedback. Common barriers include lack of confidence, inadequate support, or restrictive organisational structures.

In healthcare reforms, Dube et al. (2025) observed that training medical staff in competency frameworks was ineffective without opportunities for practice and feedback. Similarly, IT transitions often stall when employees are denied sufficient time to adapt.

ADKAR emphasises mentoring, coaching, and incremental practice to ensure knowledge translates into consistent behaviour. Ability reflects the moment when change becomes operational reality.

5.0 Reinforcement to Sustain Outcomes

The final stage of ADKAR underscores the importance of reinforcement to prevent regression. Reinforcement mechanisms include recognition, rewards, cultural embedding, and continuous monitoring.

Hiatt and Creasey (2012) note that reinforcement sustains behavioural change by making it part of organisational norms. For example, in higher education, reinforcement occurs when performance evaluations align with new pedagogical standards. In IT system rollouts, ongoing helpdesks and rewards for early adopters encourage long-term commitment.

Reinforcement ensures change is not temporary but becomes a sustained transformation embedded within organisational culture.

Strengths of the ADKAR Model

The ADKAR model’s greatest strength lies in its focus on the individual. Unlike structural approaches, it acknowledges that organisational change is the aggregate of individual transitions. This person-centred orientation fosters employee engagement and psychological safety.

Second, its diagnostic capability allows leaders to identify where change initiatives fail—whether due to lack of awareness, motivation, skills, or reinforcement (Hiatt, 2006). This practical clarity makes ADKAR widely used in consulting and corporate training.

Third, ADKAR aligns with modern calls for ethical and participatory change management. Memana (2025) emphasises its contribution to sustainable outcomes by integrating employee voices rather than imposing top-down directives.

Critiques and Limitations

Despite its strengths, scholars note limitations. Critics argue that ADKAR overemphasises the individual, sometimes neglecting structural and systemic barriers such as organisational politics, culture, or external constraints (Burnes, 2017).

Additionally, the model is perceived as linear, while in reality, change is often iterative and cyclical (By, 2005). Employees may move back and forth across stages rather than progressing sequentially.

Finally, ADKAR requires substantial leadership commitment to personalised interventions, which may be resource-intensive in large organisations. Without such investment, its principles risk superficial application.

Practical Applications

- IT System Rollouts: Hiatt & Creasey (2012) demonstrated that ADKAR can diagnose resistance points—such as lack of awareness or insufficient training—allowing targeted interventions.

- Healthcare Transformation: Hopkinson (2024) showed ADKAR’s value in introducing continuous glucose monitoring, ensuring clinicians progressed through each stage before adoption.

- Higher Education Reform: Kezar (2014) documented ADKAR’s application in aligning teaching practices with inclusivity goals, fostering cultural change among faculty.

- Corporate Mergers: In mergers, ADKAR addresses emotional resistance by building desire and reinforcing unity, helping employees transition smoothly (Hiatt, 2006).

The ADKAR model, developed by Jeff Hiatt (2006), represents a significant evolution in change management by shifting focus from organisational systems to individual adoption. Its five stages—Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement—offer a practical, diagnostic tool for guiding employees through transformation.

Examples from IT, healthcare, and education confirm its applicability across diverse contexts, while modern research underscores its alignment with participatory and ethical management practices (Memana, 2025).

Nonetheless, its limitations—notably its linearity and focus on the individual over systemic dynamics—require complementary approaches. Leaders must apply ADKAR flexibly and iteratively, integrating it with structural models to address broader organisational realities.

Ultimately, ADKAR’s strength lies in reminding leaders that successful change is not simply an organisational initiative but a human journey, where sustainable outcomes depend on the adoption, ability, and reinforcement of each individual.

References

Burnes, B. (2017). Managing Change. 7th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education.

By, R.T. (2005). Organisational change management: A critical review. Journal of Change Management, 5(4), pp.369–380.

Hiatt, J. (2006). ADKAR: A Model for Change in Business, Government and our Community. Loveland, CO: Prosci.

Hiatt, J. & Creasey, T.J. (2012). Change Management: The People Side of Change. Loveland, CO: Prosci.

Hopkinson, L. (2024). Detecting Hypoglycemia in the Hospital by Continuous Glucose Monitoring. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/openview/b988b06ec0cfa13959ff269749100699

Kezar, A. (2014). How colleges change: Understanding, leading, and enacting change. Routledge.

Kezar, A. & Eckel, P. (2002). Examining the institutional transformation process: The importance of sensemaking, interrelated strategies, and balance. Research in Higher Education, 43(3), pp.295–328.

Memana, T. (2025). Ethical participatory approaches in organisational change: Aligning ADKAR with employee engagement. Journal of Organisational Transformation, 12(1), pp.44–61.

Somers, T.M. & Nelson, K. (2001). The impact of critical success factors on ERP implementation. Business Process Management Journal, 7(3), pp.285–296.