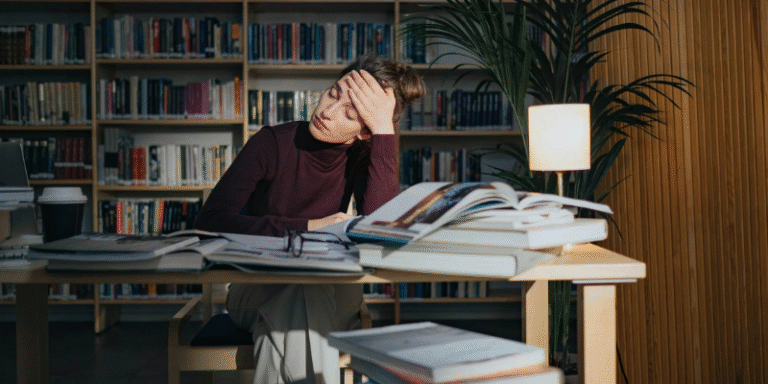

Burnout syndrome is increasingly recognised as a significant public health issue and occupational hazard in modern life. Defined as a state of prolonged psychological stress, it is most commonly associated with the workplace but can affect individuals in many domains of life, including caregiving, studying, and volunteering. Burnout is characterised by emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion, as well as a growing sense of cynicism and reduced professional efficacy (Maslach and Leiter, 2016). With chronic exposure to stressors and inadequate coping strategies, individuals can find themselves in a downward spiral affecting their wellbeing, productivity, and relationships.

What is Burnout?

The term “burnout” was first popularised by psychologist Herbert Freudenberger in 1974. He described it as a state of mental and physical exhaustion caused by one’s professional life (Freudenberger, 1982). The World Health Organization (2019) now classifies burnout as an “occupational phenomenon” in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), noting that it results from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.

Burnout has three main dimensions:

1.0 Exhaustion – feeling emotionally and physically depleted.

2.0 Depersonalisation – developing a cynical or detached attitude towards work.

3.0 Reduced personal accomplishment – experiencing a sense of failure and lack of achievement.

The Cycle of Burnout

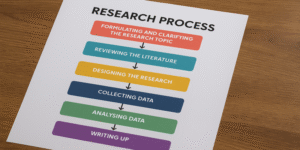

Burnout does not happen overnight but follows a progressive cycle. The visual model by Six Seconds (2024), adapted from Freudenberger’s earlier work, illustrates this in phases:

1.0 Overdoing: It starts with working harder due to the compulsion to prove oneself.

2.0 Stagnation: As self-care declines, motivation wanes and conflicts are displaced.

3.0 Frustration: Denial of problems leads to the revision of personal values and meaning.

4.0 Apathy: Withdrawal, behavioural changes, and low energy set in.

5.0 Problem: Eventually, the cycle deepens into depression and chronic distress.

This model emphasises how burnout is not a singular event but a series of choices and pressures that, over time, erode resilience and capacity.

Signs and Symptoms of Burnout

1.0 Physical Symptoms

- Chronic fatigue, headaches, gastrointestinal problems, and muscle pain are common.

- Sleep disturbances such as insomnia or excessive sleeping may also occur.

- Appetite changes, often leading to weight loss or gain, are another indicator.

According to Shirom (2005), the physiological stress response, involving the HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis, may become dysregulated in those experiencing burnout.

2.0 Emotional Symptoms

- Feelings of helplessness, defeat, and detachment are prevalent.

- Burnout may mimic or lead to clinical depression or anxiety.

- A loss of joy or interest in previously enjoyable activities is typical.

Maslach and Leiter (2016) noted that the emotional toll often precedes the physical signs, making early recognition essential.

3.0 Cognitive Symptoms

- Difficulty concentrating and forgetfulness are common.

- Decision-making becomes harder, often accompanied by self-doubt.

- Burnout affects executive functioning and mental clarity (Bianchi et al., 2015).

4.0 Behavioural Symptoms

- Increased absenteeism, reduced performance, and procrastination.

- Avoidance of responsibilities and reliance on unhealthy coping mechanisms like overeating or substance use.

- Withdrawal from social or professional interactions.

5.0 Interpersonal Symptoms

- Strained relationships with colleagues, friends, or family.

- Irritability, impatience, and poor communication are often reported.

- Feelings of isolation may emerge, worsening the emotional toll.

Causes and Risk Factors

- Burnout is multifactorial. Contributing factors include:

- Workload: Excessive demands with insufficient time or resources.

- Control: Lack of autonomy or decision-making power.

- Reward: Inadequate recognition or compensation.

- Community: Poor social support or toxic work environments.

- Fairness: Perceived inequality or discrimination.

Values: Conflict between personal ethics and organisational practices (Maslach and Leiter, 2016).

Those in caregiving roles, such as healthcare professionals, teachers, and social workers, are particularly at risk. Students, parents, and entrepreneurs are also vulnerable due to the high demands and low external structure in these roles.

Prevention and Management

1.0 Individual Strategies

- Self-care: Prioritise sleep, nutrition, and regular physical activity.

- Mindfulness and relaxation: Techniques like meditation, breathing exercises, or yoga reduce physiological stress (Grossman et al., 2004).

- Boundaries: Set clear limits on work hours and digital connectivity.

- Seek help: Engage in therapy or counselling when needed.

2.0 Workplace Interventions

- Encourage open communication about stress and workloads.

- Offer flexible scheduling and remote work where feasible.

- Implement employee wellness programmes that include mental health support.

- Train leaders in emotional intelligence to foster supportive management (Goleman, 1996).

3.0 Systemic Solutions

- Policy reforms that limit excessive overtime and promote mental health days.

- Educational institutions embedding emotional regulation into curricula.

- Public awareness campaigns to reduce stigma around stress and burnout.

Burnout syndrome is more than just being tired or overworked—it’s a serious condition with physical, emotional, and psychological consequences. By understanding the signs, causes, and prevention strategies, individuals and organisations alike can combat this growing epidemic. Efforts must be holistic, addressing not only individual behaviours but also systemic structures that contribute to chronic stress. Investing in wellbeing is not just a moral imperative—it is essential for sustainable performance and human flourishing.

References

Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I.S. and Laurent, E., 2015. Burnout-depression overlap: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 36, pp.28-41.

Freudenberger, H.J., 1982. Burn-Out: The High Cost of High Achievement. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Goleman, D., 1996. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. London: Bloomsbury.

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S. and Walach, H., 2004. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), pp.35-43.

Maslach, C. and Leiter, M.P., 2016. Burnout: A Multidimensional Perspective. In: L. Cooper and J. Campbell Quick, eds., The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide to Research and Practice. Wiley Blackwell, pp.103-120.

Shirom, A., 2005. Reflections on the study of burnout. Work & Stress, 19(3), pp.263-270.

Six Seconds, 2024. Burnout Syndrome Model. [image] Available at: https://www.6seconds.org/ [Accessed 3 June 2025].

World Health Organization, 2019. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. [online] Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019 [Accessed 3 June 2025].