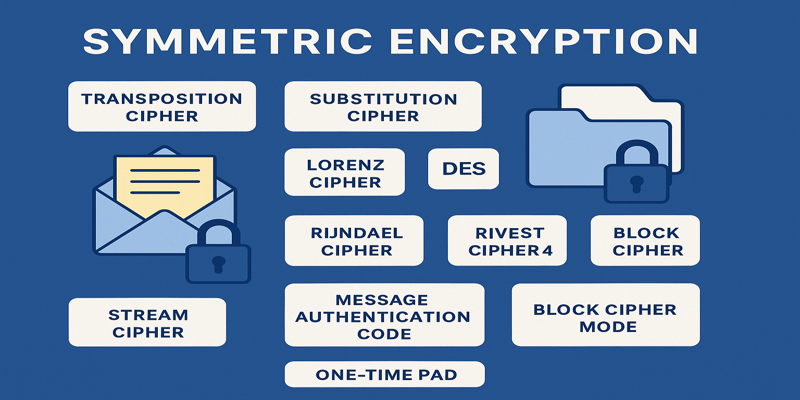

Symmetric Encryption: Principles, Applications, and Techniques

Symmetric encryption is a foundational technique in the realm of information security, involving the use of a single shared key for both encryption and decryption of data. It underpins secure communication in many systems, from messaging platforms to cloud storage services. This article explores the essential mechanisms and categories of symmetric encryption, including historical and modern ciphers, their use cases, and how they contribute to ensuring confidentiality and integrity. 1.0 Historical Ciphers in Symmetric Encryption 1.1 Transposition and Substitution Ciphers Transposition ciphers reorder the characters of the plaintext without altering the actual characters. An example is the Rail Fence cipher, where characters are written in a zigzag pattern and then read row by row. In contrast, substitution ciphers replace each character with another, such as the Caesar cipher, which shifts characters by a fixed number (Stallings, 2017). These classical methods illustrate the earliest use of symmetric encryption but are easily broken with modern computational power. Despite this, they laid the groundwork for the conceptual development of modern algorithms. 1.2 Lorenz Cipher The Lorenz cipher was a more sophisticated machine cipher used by Nazi Germany during World War II for high-level communications. It employed a series of pseudo-random keys generated through wheel-based mechanisms. Its eventual cracking by British cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park marked a turning point in the war and demonstrated the critical role of cryptography (Kahn, 1996). 2.0 Modern Symmetric Ciphers 2.1 Feistel Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) The Feistel structure is a key innovation in modern encryption algorithms. It divides the plaintext into two halves and applies a series of transformations, swapping and mixing data iteratively. The Data Encryption Standard (DES), developed in the 1970s, is based on this architecture. Although it became a widely adopted standard, DES has since been deprecated due to its short 56-bit key, which is vulnerable to brute-force attacks (Agal & Sharma, 2014). 2.2 Triple Data Encryption Standard (3DES) To enhance DES, the Triple DES (3DES) algorithm applies the DES encryption process three times with different keys, effectively increasing the key length to 168 bits. This mitigated many of the original DES vulnerabilities, though at the cost of slower performance (Abood & Guirguis, 2020). However, with the rise of more efficient algorithms, 3DES is now largely obsolete in favour of Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). 3.0 Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) and Rijndael Cipher The Rijndael cipher, selected as the AES in 2001 by NIST, is a symmetric block cipher supporting 128, 192, or 256-bit keys. AES operates on a 4×4 byte matrix using substitution-permutation operations across multiple rounds (Stallings, 2017). It is known for its security and efficiency, making it the de facto standard for encrypting sensitive data in both governmental and commercial applications. Recent research has extended AES applications into areas like DNA computing, highlighting its versatility and adaptability to new computational models (Abood & Guirguis, 2020). 4.0 Stream Ciphers Stream ciphers encrypt data one bit or byte at a time, often using a pseudorandom keystream. A notable example is Rivest Cipher 4 (RC4). Known for its simplicity and speed, RC4 was widely used in SSL/TLS protocols. However, flaws in its key scheduling algorithm led to several vulnerabilities, prompting its deprecation in modern cryptographic standards (Tolba, 2024). 5.0 Block Cipher Modes and Key Algorithms 5.1 Blowfish and Twofish Blowfish is a symmetric block cipher designed by Bruce Schneier in 1993. It features a variable-length key and operates on 64-bit blocks. It is particularly valued for its speed and free licensing. Twofish, a successor to Blowfish, was one of the five finalists in the AES competition. It improves upon Blowfish with more complex key scheduling and 128-bit block size (Agal & Sharma, 2014). 5.2 Rivest Cipher 5 (RC5) RC5 is another block cipher with variable parameters: block size, key size, and number of rounds. It incorporates data-dependent rotations, making cryptanalysis more difficult. However, its variable complexity also makes it more computationally intensive (Abood & Guirguis, 2020). 6.0 Message Authentication Code (MAC) MACs are crucial for ensuring the integrity and authenticity of messages. They work by combining a secret key with the message data through a cryptographic hash or cipher, producing a short fixed-length code. If the message or the MAC is altered during transmission, the verification fails (Stallings, 2017). This technique is used in protocols like IPsec and TLS to prevent tampering and impersonation. 7.0 One-Time Pad The one-time pad (OTP) is a theoretically unbreakable cipher when implemented correctly. Each bit or character of the plaintext is encrypted using a unique, random key of the same length. However, OTP’s impractical requirements—especially secure key distribution and disposal—limit its usage to scenarios requiring the highest level of secrecy, such as diplomatic or military communication (Beebe, 2004). 8.0 Applications: Messaging and Cloud Storage Symmetric encryption underpins secure messaging services like Signal and WhatsApp, where fast encryption and decryption are critical. AES is commonly used due to its speed and robustness. In cloud storage, symmetric encryption ensures that user files are protected from unauthorised access. For example, Google Cloud and AWS employ AES-256 encryption for data-at-rest security. Furthermore, symmetric ciphers are often used in tandem with asymmetric cryptography. For instance, symmetric keys are transmitted securely using public-key encryption and subsequently used to encrypt data due to their efficiency in handling large volumes (Stallings, 2017). Symmetric encryption continues to be a cornerstone of modern cybersecurity infrastructure. From the rudimentary transposition and substitution ciphers to sophisticated systems like AES and Blowfish, symmetric algorithms have evolved significantly. Their efficiency, particularly for encrypting large data volumes, makes them indispensable in contemporary applications, including secure communications, cloud storage, and embedded systems. However, they must be implemented with care—incorporating secure key management and robust protocols to mitigate potential vulnerabilities. References Agal, M.S. & Sharma, A., 2014. Comparative Study of Symmetric Cryptography Algorithm. ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286863418_Comparative_Study_of_Symmetric_Cryptography_Algorithm [Accessed 26 Jun. 2025]. Abood, O.G. & Guirguis, S., 2020. Enhancing Cryptographic Security based on AES and DNA Computing. ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339999643_Enhancing_Cryptographic_Security_based_on_AES_and_DNA_Computing [Accessed 26 Jun. 2025]. Beebe, N.H.F., 2004. A Bibliography of Publications on Cryptography: 1606–1999. … Read more