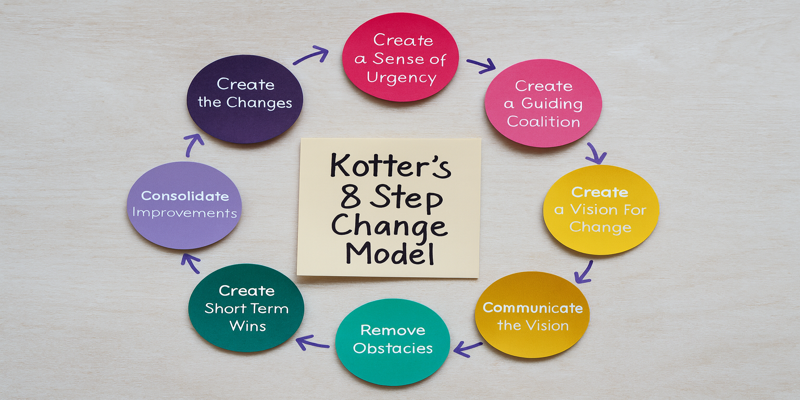

Kotter’s 8-Step Process for Leading Change

Organisational change is an inevitable reality in today’s dynamic and competitive business environment. In response to increasing complexity, John Kotter (1996) developed the 8-Step Process for Leading Change, expanding on Kurt Lewin’s earlier unfreeze–change–refreeze model. Kotter’s 8-Step Process for Leading Change framework provides a structured roadmap for organisations to manage transformation effectively, particularly in contexts such as mergers, digital transformation, and sustainability initiatives. Despite its widespread adoption, scholars argue that the model’s linear design may not reflect the iterative realities of contemporary organisational change (Suh et al., 2025). This article critically examines Kotter’s framework, applying examples from business and healthcare, and evaluates both its strengths and limitations. 1.0 Creating a Sense of Urgency Kotter (1996) argued that change begins with urgency; organisations must highlight risks of inaction to mobilise stakeholders. Without urgency, resistance dominates. For instance, during Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan, urgency around climate change drove environmental initiatives, framing sustainability not only as ethical but also as essential for competitiveness (Unilever, 2023). Recent studies reaffirm urgency’s role in digital change. Komna and Mpungose (2024) found that in South Africa’s public sector IT reforms, leaders who established urgency by highlighting inefficiencies achieved higher stakeholder buy-in. Conversely, failing to communicate urgency often results in complacency and failed reforms. 2.0 Forming a Powerful Coalition A second critical step is building a coalition of influential leaders who can steer change. Kotter (1996) emphasised leadership beyond formal hierarchy, noting that symbolic and charismatic leaders can mobilise diverse stakeholders. Vijaykumar, Das and Sixl-Daniell (2025), in their study of Twitter’s buy-out and transition into “X,” observed that successful coalitions often blend executives, middle managers, and cultural influencers. Without such a coalition, leadership fragmentation undermines credibility. In healthcare contexts, Tsatsou (2025) showed that oncology nursing reforms required multidisciplinary leadership groups, reinforcing Kotter’s insight. 3.0 Creating a Vision for Change The third step involves crafting a compelling vision that aligns strategy, people, and operations. A vision provides clarity and direction in times of uncertainty. In medical education reform in the UAE, Dube et al. (2025) demonstrated that developing a shared vision of competency-based education aligned stakeholders and reduced resistance. Similarly, Spicer (2025) found that in post-secondary mental health initiatives in Canada, a clear vision helped overcome fragmented institutional practices. Without a strong vision, organisational change risks becoming a series of disjointed activities rather than a coherent transformation. 4.0 Communicating the Vision Kotter stressed that communication must be continuous, multi-channel, and repetitive to ensure clarity. Leaders must model behaviours aligned with the vision. Mendez (2024) showed in nursing burnout interventions that clear communication across professional levels helped sustain morale. Similarly, Seufert and Ju (2025) reported that when Z-Group implemented robotics for store cleaning, leaders who communicated frequently achieved higher levels of employee trust. Failure to communicate adequately leads to misinformation and resistance, a recurring theme in change management failures (Abernathy, 2025). 5.0 Removing Obstacles Structural, cultural, or psychological barriers must be addressed. Empowering staff with authority and resources is critical for momentum. Wong et al. (2025) described how implementing a surgical risk calculator in Hong Kong hospitals required removing bureaucratic bottlenecks and granting staff autonomy to act. Similarly, Karimi and Ljungqvist (2025) emphasised that in banking and real estate reforms, obstacle removal—including outdated IT systems—was a prerequisite for sustainable change. Obstacles left unresolved undermine credibility and stall progress. 6.0 Creating Short-Term Wins Kotter highlighted the importance of visible, early successes to build momentum and silence sceptics. Valenza et al. (2025), in oral healthcare reform, documented that celebrating pilot programme results boosted confidence in broader changes. Dillard (2025) also observed that consulting firms utilising short-term wins as part of Kotter’s framework secured client trust faster. Short-term wins not only reinforce urgency but also reduce resistance by proving that change is achievable. 7.0 Building on the Change Rather than declaring victory prematurely, Kotter argued for consolidating gains and embedding change deeper. In the digital transformation of healthcare, Subramani (2025) noted that transformational leaders sustained commitment by reinforcing cultural narratives of loyalty and continuous improvement. Similarly, Suh et al. (2025) stressed that in family medicine residency programmes, iterative reinforcement of Kotter’s steps was essential, as change is rarely linear. This step underscores the need for change as an ongoing process rather than a one-off event. 8.0 Anchoring Changes in Culture Finally, Kotter (1996) argued that changes must be embedded in organisational culture to ensure long-term sustainability. Values, rituals, and policies must reflect new behaviours. Gómez Cortés and Ramirez Orozco (2025) observed that many change efforts fail because organisations neglect cultural embedding, leading to regression. In contrast, Unilever’s sustainability initiatives succeeded because environmental values became ingrained in brand identity. Anchoring change requires both structural reinforcement and symbolic alignment with values. Critical Perspectives While Kotter’s model remains one of the most influential change frameworks, scholars have criticised its sequential and linear design. Suh et al. (2025) and Rodríguez Villanueva and Schwarz (2025) highlight that real-world change is iterative and cyclical, not strictly stepwise. Moreover, modern contexts such as digital transformation and artificial intelligence adoption require agility and rapid adaptation beyond Kotter’s original framework (Houston Jackson, 2025). Nevertheless, Kotter’s emphasis on urgency, vision, communication, and culture remains highly relevant, particularly in large-scale, complex changes (Komna & Mpungose, 2024). Kotter’s 8-Step Process for Leading Change provides a powerful roadmap for managing organisational transformation. Its strengths lie in its clarity, comprehensiveness, and emphasis on both leadership and culture. Applications in sustainability, digital transformation, and healthcare confirm its enduring relevance. However, its limitations—particularly its linearity and assumption of predictable stages—require adaptation in contemporary, complex environments. Leaders must apply Kotter’s principles flexibly, integrating them with iterative, adaptive approaches such as agile change management. Ultimately, Kotter’s model remains an indispensable foundation for understanding and navigating organisational change, but it must be seen as a guideline rather than a rigid formula. References Abernathy, A. (2025). Exploring the Challenges Faced by Organisational Change Leaders: A Qualitative Study. ProQuest. Dillard, D. (2025). A Mixed Methodology Study on Effective Products and Services for Consulting Firms. Gardner-Webb University. Dube, R., George, B.T., & Kar, S.S. … Read more