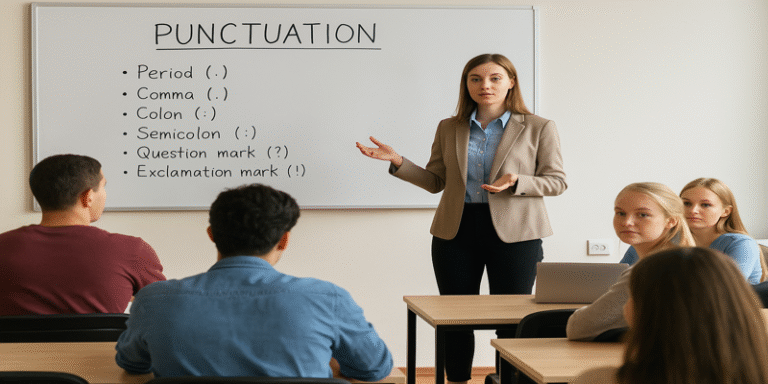

Punctuation is a cornerstone of written communication, providing clarity, rhythm, and precision. While spoken language relies on intonation, pauses, and gestures to convey meaning, written language depends heavily on punctuation marks to guide interpretation. As Truss (2003) notes, poor punctuation can obscure meaning and even lead to miscommunication. This article explores the history, purpose, and practical use of punctuation in academic writing, focusing on the most common punctuation marks.

Historical Background

The origins of punctuation can be traced back to Aristophanes of Byzantium, who developed early systems of marks around 200 BC to aid oral reading (Parkes, 1993). However, the modern system emerged in the 15th century with the invention of printing, when printers like Aldus Manutius standardised punctuation for clarity (Crystal, 2019). Since then, punctuation has been regarded as essential for effective literacy, enabling writers to structure complex ideas and readers to interpret them correctly.

Functions of Punctuation

The primary function of punctuation is to make writing understood with clarity (Punctuation.docx, 2018). It performs two key roles:

- Aiding comprehension – helping readers decode sentence structure and intended meaning.

- Enhancing flow – providing rhythm and emphasis, much like pauses and stress in spoken language.

Thus, punctuation is both mechanical (rule-based) and rhetorical (expressive).

Full Stop (.)

Known in British English as a full stop, this mark signals the end of a complete sentence. It is also used in abbreviations and acronyms (e.g., U.K., though modern usage often omits the stops). According to Trask (1997), overuse of commas where full stops should appear is a frequent error, leading to confusing run-on sentences.

Example:

- Correct: She enjoys research. She also teaches linguistics.

- Incorrect: She enjoys research, she also teaches linguistics.

Comma (,)

The comma is one of the most versatile and misused punctuation marks. It has several functions (Punctuation.docx, 2018):

- Listing: separating items (I bought apples, oranges, and pears).

- Joining: connecting independent clauses with conjunctions (I could tell you the truth, but I will not).

- Bracketing: setting off non-essential clauses (My tutor, who is very experienced, explained the theory).

- Gapping: showing omitted words (Some students study punctuation carefully; others, less so).

The controversial Oxford comma (before the final “and” in a list) is rarely used in British English, except when needed to avoid ambiguity (Garner, 2016).

Colon (:)

The colon introduces explanations, lists, or restatements. It links a general statement to a more specific one (Crystal, 2019).

Examples:

- She had three goals: to graduate, to travel, and to start work.

- Gabrielle was in pain: she had sprained her ankle.

In academic writing, colons are particularly useful for signalling emphasis and clarity.

Semicolon (;)

The semicolon is often misunderstood but plays a vital role in linking closely related clauses without a conjunction. It is stronger than a comma but weaker than a full stop (Trask, 1997).

Examples:

- He loved reading; he could not get enough of books.

- The speakers included: Tony Blair, Prime Minister; Gordon Brown, Chancellor; and Ruth Kelly, Education Secretary.

In student essays, misuse of semicolons is common, but mastering them adds sophistication to writing.

Question Mark (?)

A question mark concludes a direct question. It should not be used with indirect questions (Punctuation.docx, 2018).

Examples:

- Direct: Where do you live?

- Indirect: He asked where I lived. (no question mark)

It may also indicate uncertainty within brackets (He was born in 1886(?) and died in 1942).

Exclamation Mark (!)

The exclamation mark signals strong feeling, surprise, or emphasis. However, it should be used sparingly in academic writing, where tone should remain objective (Cutts, 2020).

Examples:

- What a wonderful discovery!

- I can’t believe the results!

In scholarly contexts, exclamation marks are rare, appearing mostly in quotations.

Apostrophe (’)

The apostrophe is frequently misused. Its correct uses are:

- Contractions (it’s = it is).

- Possession (the researcher’s notes).

Errors include using apostrophes for plurals (CD’s instead of CDs), confusing its and it’s, and mixing whose and who’s. According to the Apostrophe Protection Society (2019), such errors are widespread in public writing, despite clear rules.

Hyphen (-) and Dash (–)

The hyphen links words (no-smoking sign, well-known author) or prevents ambiguity (re-cover vs recover).

The dash, longer than a hyphen, is used to mark strong interruptions or additional emphasis (All nations desire growth – some even achieve it – but it is easier said than done). While effective stylistically, dashes should be used sparingly in formal writing (Truss, 2003).

Quotation Marks (“ ”)

Quotation marks enclose direct speech or citations. British English often prefers single quotation marks (‘ ’), while double marks (“ ”) are common in American usage. Only punctuation that belongs to the quotation itself should appear inside the marks.

Examples:

- Correct: He said, “I am leaving now.”

- Incorrect: He said, “I am leaving now”. (British convention differs from American here).

Quotation marks are also used for scare quotes, signalling irony or doubt (He claimed to be an “expert”).

Brackets () and Ellipsis (…)

Brackets (parentheses) enclose supplementary information (The study was conducted in London (UK) over three years).

Ellipsis (…) shows omissions, unfinished thoughts, or suspense (The winner is …). In academic referencing, ellipses indicate omitted words in quotations (APA, 2020).

Importance of Correct Punctuation

Correct punctuation enhances both clarity and professionalism. Poor punctuation not only obscures meaning but also undermines credibility. For example, compare:

- Let’s eat, grandma.

- Let’s eat grandma.

The first, correctly punctuated, is an invitation; the second is alarming. Such examples illustrate Lynne Truss’s (2003) warning that “proper punctuation is both the sign and the cause of clear thinking.”

Punctuation is more than a set of arbitrary rules; it is integral to clear academic writing. From the basic full stop to the nuanced semicolon, punctuation marks enable writers to convey precise meaning and structure complex ideas. Mastery of punctuation enhances both clarity and persuasiveness, contributing to academic success. As Trask (1997) and Truss (2003) argue, punctuation is not merely mechanical—it reflects clarity of thought. Students and researchers must therefore prioritise accurate punctuation, recognising it as a vital academic skill.

References

Apostrophe Protection Society (2019). Apostrophe rules. Available at: https://www.apostrophe.org.uk (Accessed: 8 September 2025).

APA (2020). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association. 7th ed. Washington, DC: APA.

Crystal, D. (2019). Making a Point: The Pernickety Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Books.

Cutts, M. (2020). Oxford Guide to Plain English. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garner, B. (2016). Garner’s Modern English Usage. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Parkes, M. (1993). Pause and Effect: An Introduction to the History of Punctuation in the West. Aldershot: Scolar Press.

Punctuation.docx (2018). Punctuation Resource.

Trask, R.L. (1997). The Penguin Guide to Punctuation. London: Penguin.

Truss, L. (2003). Eats, Shoots and Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation. London: Profile Books.