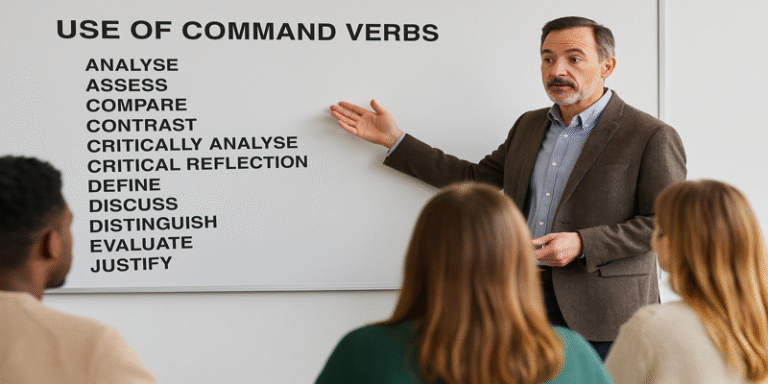

Producing high-quality academic work requires not only knowledge of the subject but also an understanding of how questions are framed. The command words used in assignment briefs, such as analyse, evaluate, or discuss, provide explicit instructions on how to approach a task. Recognising and accurately responding to these instructional verbs is a critical academic skill that demonstrates comprehension, analytical thinking, and intellectual rigour (Cottrell, 2019). This article explores the meanings of commonly used command words, their implications for academic writing, and strategies for applying them effectively in higher education.

1.0 The Importance of Understanding Command Words

At the core of academic success lies the ability to interpret assignment questions correctly. According to Cottrell (2019), misunderstanding the task is one of the most common reasons students underperform in assessments. Command words act as cognitive signposts, guiding the depth, structure, and tone of an academic response. For instance, a question beginning with “Evaluate” requires a balanced judgement supported by evidence, while “Describe” merely demands factual explanation.

Moon (2013) emphasises that academic performance is determined not just by knowledge recall but by critical engagement with information. Therefore, identifying the command word allows learners to align their writing style and argument structure with the examiner’s expectations. For example, a command word like “Critically analyse” demands a higher level of cognitive processing than “Explain” — moving beyond description towards critique and synthesis (Bloom, 1956).

2.0 Common Command Words and Their Academic Implications

Analyse

To analyse means to examine in detail the constituent parts of an idea, concept, or issue and explore their relationships. As Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) note in their revision of Bloom’s taxonomy, analysis occupies a mid-level cognitive domain, demanding understanding and interpretation. For instance, when analysing a company’s marketing strategy, a student must dissect the campaign — considering objectives, target audience, promotional channels, and outcomes — rather than merely describing what the campaign involved. A good analytical answer often includes linkages between causes and consequences and employs evidence-based reasoning.

Assess

The word assess requires a student to weigh up strengths and weaknesses, or the importance of different factors. According to Burns and Sinfield (2016), assessment in writing involves judgement informed by criteria or evidence. For example, when asked to assess the effectiveness of a company’s leadership style, the student should explore both the style’s success in motivating employees and its potential drawbacks, such as overreliance on autocratic decision-making in dynamic business environments.

Compare and Contrast

To compare means to look for similarities, while to contrast emphasises differences. As Gillet (2022) explains, effective comparative writing often uses paired evidence and clear structure, allowing the reader to discern relationships and distinctions. For instance, comparing Porter’s Five Forces and the PESTLE framework requires identifying their overlapping functions (e.g., analysing external influences on a business) as well as contrasting features (e.g., industry-level vs. macro-environmental focus).

Critically Analyse

Perhaps one of the most demanding command words, critically analyse requires both evaluation and judgement. According to Redman and Maples (2017), critical analysis involves examining strengths and weaknesses, questioning assumptions, and considering alternative perspectives. In business management, for example, a critical analysis of corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives might involve balancing the reputational benefits of ethical branding against potential cost implications and stakeholder scepticism.

Define

The simplest but most fundamental task, to define means to state the exact meaning of a term or concept. As Harris and McPherson (2018) note, a good definition should be concise, precise, and, where relevant, referenced from an authoritative source. For instance, defining strategic management using Johnson, Whittington and Scholes (2017) would involve identifying it as “the direction and scope of an organisation over the long term, which achieves advantage through its configuration of resources within a changing environment.”

Discuss

When asked to discuss, a student should present arguments for and against a proposition, before reaching a reasoned conclusion. Northedge (2005) argues that discussion-type questions assess a learner’s ability to synthesise multiple viewpoints. For example, discussing the impact of globalisation on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) involves weighing its benefits in terms of market access and innovation against challenges such as increased competition and cultural adaptation.

Evaluate

To evaluate requires students to make a value judgement based on evidence. As Stella Cottrell (2019) states, evaluation demands both critical thinking and the ability to justify conclusions. For example, evaluating the use of transformational leadership in organisational change would require examining its effectiveness in motivating employees, its alignment with corporate culture, and potential challenges in maintaining consistency across large teams.

Justify

When an assignment requires you to justify, you must defend a position or argument with evidence or reasoning. For instance, justifying the adoption of a hybrid working model involves citing evidence of increased employee satisfaction, cost efficiency, and productivity outcomes in post-pandemic organisations.

Illustrate

To illustrate means to clarify through examples or visual aids. As Lea and Street (2014) observe, illustration deepens understanding by connecting theory to practice. For example, illustrating the process of strategic planning might involve a step-by-step diagram of SWOT analysis leading to objective setting and implementation planning.

3.0 The Role of Critical Reflection

Another advanced command often found in higher education is critical reflection. This goes beyond merely recalling what was done — it involves interpreting experiences and drawing lessons for future practice (Kolb, 1984). Critical reflection, as Schön (1983) explains, is a means of transforming experience into learning by examining underlying assumptions. In business management, reflecting on a previous group project on market entry strategy might reveal gaps in communication, delegation, or risk assessment, leading to improved teamwork and project management skills.

For instance, after completing a business simulation exercise, a student might critically reflect on how overlooking competitor pricing data led to reduced market share. This reflection demonstrates both self-awareness and application of professional standards — key traits in managerial and academic growth.

4.0 Strategies for Applying Command Words Effectively

Understanding command words is not enough; students must also translate them into structured academic writing. According to Bailey (2018), effective responses use academic language, logical progression, and evidence-based argumentation. Practical strategies include:

- Highlighting the command word in each assignment brief before planning.

- Breaking down the question into smaller tasks (e.g., identify what to explain, what to compare, and what to conclude).

- Using academic models such as Bloom’s taxonomy to gauge the cognitive level required.

- Using transitional phrases like “on the other hand”, “similarly”, and “in contrast” to support comparative and evaluative writing.

These strategies enhance clarity and coherence, helping students address the specific academic expectations of their discipline.

Understanding and applying command words effectively is crucial for achieving academic excellence. Each command word directs the depth, tone, and analytical level of a response. From simple tasks like define and state, to complex intellectual operations such as critically analyse and evaluate, command words provide the structure for critical thinking and scholarly writing. Students who master these terms not only meet assessment criteria but also develop transferable skills of reasoning, analysis, and reflection that are vital for professional practice.