Food intolerances are increasingly recognised as significant contributors to gastrointestinal discomfort and reduced quality of life. Unlike food allergies, which involve the immune system and may be life-threatening, food intolerances typically result from difficulties in digestion or sensitivity to certain food components. Although often confused with allergies, intolerances involve distinct physiological mechanisms. This article explores the scientific basis of food intolerances, common types, diagnostic approaches, and evidence-based management strategies, drawing on textbooks, peer-reviewed research, and reputable health organisations.

1.0 Food Intolerance vs Food Allergy: A Critical Distinction

One of the most important distinctions in clinical nutrition is between food allergy and food intolerance. Food allergies involve an immune-mediated response, typically IgE-mediated hypersensitivity, which can cause urticaria, anaphylaxis, and respiratory compromise (Kumar, Abbas and Aster, 2020). In contrast, food intolerances are usually non-immune reactions, often related to enzyme deficiencies, pharmacological effects of food components, or gastrointestinal sensitivity (Gibney et al., 2019).

For example:

- Food allergy → Immediate immune response (e.g., peanut allergy).

- Food intolerance → Delayed digestive symptoms (e.g., lactose intolerance).

According to the NHS (2023), symptoms of food intolerance are generally less severe than allergies but may include bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, headaches, and fatigue.

2.0 Common Types of Food Intolerances

2.1 Lactose Intolerance

Lactose intolerance is one of the most prevalent food intolerances worldwide. It occurs due to reduced activity of the enzyme lactase, which is responsible for breaking down lactose, the sugar found in milk.

When lactose is not properly digested, it passes into the colon, where bacteria ferment it, producing gas and osmotic effects that lead to bloating and diarrhoea (Gibney et al., 2019).

Globally, lactase persistence varies genetically. In populations of East Asian or African descent, lactose intolerance prevalence is significantly higher compared to Northern European populations (Kumar, Abbas and Aster, 2020).

2.2 Gluten Sensitivity (Non-Coeliac)

Coeliac disease is an autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten, but some individuals experience symptoms without the characteristic intestinal damage seen in coeliac disease. This condition is termed non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS).

Research suggests that symptoms may relate not only to gluten but also to fermentable carbohydrates such as FODMAPs (Biesiekierski et al., 2013). Symptoms often include abdominal pain, bloating, and fatigue.

It is essential to differentiate NCGS from coeliac disease through proper medical testing before dietary restriction.

2.3 Histamine Intolerance

Some individuals exhibit symptoms after consuming histamine-rich foods such as aged cheese, wine, or fermented products. Histamine intolerance may result from reduced activity of the enzyme diamine oxidase (DAO), which metabolises histamine.

Symptoms may include headaches, flushing, gastrointestinal upset, and nasal congestion (Maintz and Novak, 2007). However, diagnosis remains controversial due to lack of standardised testing.

2.5 FODMAP Intolerance and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols) are poorly absorbed carbohydrates that can trigger symptoms in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Research indicates that a low-FODMAP diet significantly reduces IBS symptoms in many patients (Halmos et al., 2014). However, such diets should be implemented under professional supervision to prevent nutritional deficiencies.

3.0 Mechanisms Underlying Food Intolerances

Food intolerances may arise through several mechanisms:

- Enzyme deficiency (e.g., lactase deficiency)

- Pharmacological reactions (e.g., caffeine sensitivity)

- Osmotic effects (unabsorbed sugars drawing water into the bowel)

- Altered gut microbiota

- Visceral hypersensitivity in IBS (Taylor, 2021)

The gut-brain axis also plays a role. Psychological stress can exacerbate gastrointestinal sensitivity, highlighting the biopsychosocial nature of digestive disorders (Taylor, 2021).

5.0 Diagnosis: Evidence-Based Approaches

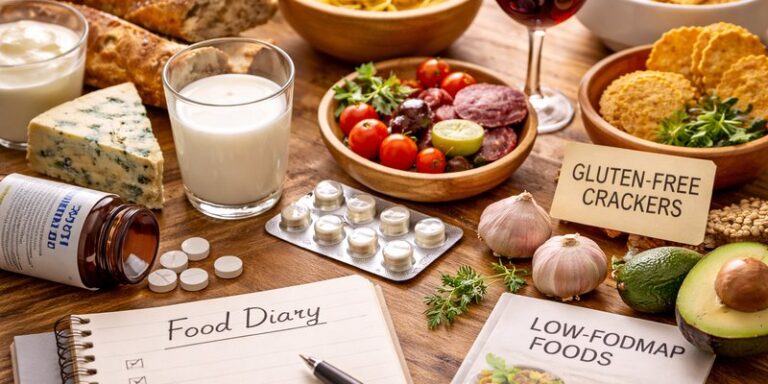

Diagnosis of food intolerance typically involves:

- Detailed dietary history

- Symptom diary

- Elimination and reintroduction protocols

- Specific tests (e.g., lactose hydrogen breath test)

The NHS (2023) cautions against unvalidated commercial “food intolerance tests”, which often lack scientific credibility.

Elimination diets should be temporary and structured, ensuring foods are reintroduced systematically to identify triggers accurately.

6.0 Psychological and Social Impact

Chronic digestive discomfort can significantly affect quality of life. Individuals with IBS or food sensitivities may experience anxiety related to eating in social settings (Halmos et al., 2014).

Furthermore, overly restrictive diets may lead to nutritional deficiencies or disordered eating patterns if not properly managed (Gibney et al., 2019).

Thus, balanced medical guidance is essential.

7.0 Management Strategies

7.1 Targeted Dietary Adjustments

Once triggers are identified, dietary modification can be effective. For example:

- Lactose intolerance → Lactose-free dairy or lactase supplements.

- FODMAP sensitivity → Structured low-FODMAP plan.

- Histamine intolerance → Limiting aged or fermented foods.

7.2 Enzyme Supplementation

Lactase supplements may reduce symptoms in lactose intolerance. Evidence supports their efficacy when taken before dairy consumption (Gibney et al., 2019).

7.3 Gut Health Optimisation

Emerging research highlights the role of gut microbiota in digestive health. Probiotics may improve symptoms in IBS, though effects vary by strain (Halmos et al., 2014).

7.4 Stress Management

Given the interaction between psychological stress and gut function, stress reduction strategies such as mindfulness or cognitive behavioural therapy may improve gastrointestinal symptoms (Taylor, 2021).

8.0 Critical Considerations

While awareness of food intolerances is important, overdiagnosis and self-imposed restrictive diets are increasing. Some individuals attribute non-specific symptoms to food intolerance without clinical confirmation.

A balanced, evidence-based approach is necessary to prevent unnecessary dietary restriction and ensure nutritional adequacy.

Food intolerances are common, multifactorial conditions involving digestive and physiological mechanisms distinct from food allergies. Conditions such as lactose intolerance, FODMAP sensitivity, and histamine intolerance demonstrate the complex relationship between diet, digestion, and overall wellbeing.

Evidence supports structured diagnosis and targeted management rather than indiscriminate dietary restriction. By combining nutritional guidance, medical evaluation, and stress management, individuals can effectively manage symptoms while maintaining a balanced diet.

Understanding food intolerances requires scientific nuance, careful assessment, and avoidance of misinformation. When properly addressed, most intolerances can be managed successfully without compromising nutritional health.

References

Biesiekierski, J.R. et al. (2013) ‘Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without coeliac disease’, Gastroenterology, 145(2), pp. 320–328.

Gibney, M.J. et al. (2019) Introduction to human nutrition. 3rd edn. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Halmos, E.P. et al. (2014) ‘A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome’, Gastroenterology, 146(1), pp. 67–75.

Kumar, V., Abbas, A.K. and Aster, J.C. (2020) Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. 10th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier.

Maintz, L. and Novak, N. (2007) ‘Histamine and histamine intolerance’, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 85(5), pp. 1185–1196.

NHS (2023) ‘Food intolerance’. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk.

Taylor, S.E. (2021) Health psychology. 11th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.