Anger is a universal human emotion that serves adaptive functions, such as signalling injustice or motivating self-protection. However, when anger becomes frequent, intense or poorly regulated, it can lead to aggression, interpersonal conflict, mental health difficulties and even criminal behaviour. Anger management refers to structured psychological strategies designed to help individuals recognise, understand and regulate anger effectively. Drawing on textbooks, peer-reviewed journal articles and reputable health organisations, this article explores symptoms, theoretical foundations, evidence-based interventions and practical applications of anger management using the Harvard referencing system.

1.0 Symptoms of Problematic Anger

While anger itself is normal, problematic anger is characterised by excessive intensity, duration or inappropriate expression. According to Deffenbacher (2011) and Shahsavarani et al. (2016), anger manifests across physiological, cognitive, emotional and behavioural domains.

1.1 Physiological Symptoms

Anger activates the body’s fight-or-flight response, leading to:

- Increased heart rate

- Elevated blood pressure

- Muscle tension (especially jaw and shoulders)

- Sweating

- Flushed face

- Trembling

- Headaches

For example, an individual experiencing road rage may notice clenched fists, rapid breathing and facial heat before shouting or gesturing aggressively.

1.2 Cognitive Symptoms

Problematic anger is often maintained by maladaptive thinking patterns, including:

- Hostile attribution bias (assuming others intend harm) (Howells and Day, 2003)

- Catastrophising (“This always happens to me”)

- Rigid beliefs (“People must respect me at all times”)

- Rumination about perceived injustices

Such thoughts escalate emotional intensity and reduce rational evaluation.

1.3 Emotional Symptoms

- Persistent irritability

- Resentment

- Frustration

- Feelings of injustice or humiliation

Sukhodolsky and Smith (2016) note that chronic irritability in children and adolescents is often associated with impaired emotional regulation skills.

1.4 Behavioural Symptoms

Behavioural indicators include:

- Shouting or verbal aggression

- Physical aggression

- Passive-aggressive behaviour

- Social withdrawal

- Property damage

- Risk-taking behaviour

In forensic populations, persistent aggressive behaviour is frequently linked to poor anger regulation (Henwood, Chou and Browne, 2015).

2.0 Understanding Anger: Theoretical Foundations

Contemporary models conceptualise anger within a biopsychosocial framework, incorporating biological arousal, cognitive appraisal and social learning (Shahsavarani et al., 2016). According to cognitive-behavioural theory (CBT), anger arises not merely from events but from how individuals interpret them (Deffenbacher, 2011).

For example, perceiving a colleague’s criticism as a personal attack rather than constructive feedback may trigger hostility.

Howells and Day (2003) emphasise cognitive distortions, such as hostile attribution bias, where ambiguous actions are interpreted as deliberately provocative. Emotion regulation research highlights that poor emotional self-regulation skills increase vulnerability to explosive anger (Eadeh et al., 2021).

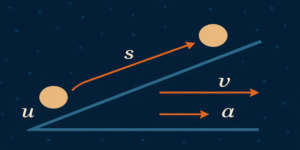

Textbooks (Attwood, 2004; Larson and Lochman, 2010) describe anger as involving three interconnected systems:

- Physiological arousal

- Cognitive processes

- Behavioural responses

Effective anger management requires intervention across all three domains.

3.0 Interventions

3.1 Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Anger

The strongest evidence base lies in cognitive-behavioural interventions. A meta-analysis by Saini (2009) found that CBT significantly reduces anger across diverse populations. Del Vecchio and O’Leary (2004) reported moderate to large effect sizes in anger reduction among adults.

CBT-based anger management typically includes:

- Psychoeducation

- Cognitive restructuring

- Relaxation training

- Problem-solving skills training

- Behavioural rehearsal

For example, a person prone to road rage may learn to recognise early physiological cues, challenge hostile thoughts and replace them with balanced alternatives.

Sukhodolsky et al. (2004) demonstrated significant reductions in anger and aggression among children and adolescents following CBT interventions.

3.2 Emotion Regulation Approaches

Recent research highlights emotion regulation (ER) as central to anger management. ER refers to the ability to monitor and modify emotional responses (Eadeh et al., 2021).

Behavioural interventions often incorporate parent management training (PMT) to address relational dynamics (Sukhodolsky and Smith, 2016).

For example, an adolescent who frequently argues with parents may learn to pause, label emotions and use coping statements before responding.

3.3 Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Mindfulness involves non-judgemental awareness of present-moment experiences. Wright, Day and Howells (2009) found that mindfulness reduces rumination and improves emotional control.

Mindfulness practices such as body scanning help individuals disengage from reactive anger patterns. However, Lee and DiGiuseppe (2018) note that CBT remains the most empirically validated approach.

4.0 Anger Management in Forensic and Clinical Settings

Anger management programmes are widely used in correctional settings. Henwood, Chou and Browne (2015) found that CBT-informed interventions reduced recidivism among offenders.

However, effectiveness depends on readiness for change (Howells and Day, 2003).

5.0 Self-Help and Community Approaches

Reputable organisations such as SAMHSA and the NHS provide structured anger management guidance (Toohey, 2021).

Self-help strategies include:

- Keeping an anger diary

- Practising assertive communication

- Regular physical activity

- Structured problem-solving

For example, an employee frustrated by workplace demands might identify triggers and rehearse constructive responses.

6.0 Limitations and Future Directions

Although CBT is effective, limitations exist. Cognitive bias modification interventions show inconsistent results (Ciesinski and Himelein-Wachowiak, 2023). Cultural considerations also influence anger expression.

Neurocognitive research (Richard et al., 2023) suggests anger involves neural networks associated with impulse control and threat processing.

Anger is not inherently negative; it becomes problematic when symptoms are intense, persistent or poorly regulated. Problematic anger manifests through physiological arousal, maladaptive cognitions, emotional dysregulation and aggressive behaviour.

Evidence strongly supports cognitive-behavioural therapy, complemented by emotion regulation and mindfulness strategies. Effective anger management promotes improved relationships, psychological wellbeing and social functioning.

Through scientifically grounded interventions and practical skill development, individuals can transform anger into a constructive signal rather than a destructive force.

References

Anjanappa, S. and Govindan, R. (2020) ‘Anger management in adolescents: A systematic review’, Indian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 17(1), pp. 1–10.

Attwood, T. (2004) Exploring feelings: Cognitive behaviour therapy to manage anger. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons.

Bulut, M. and Yüksel, Ç. (2023) ‘Self-help techniques in anger management with cognitive behavioural interventions’, Humanistic Perspective, 5(2), pp. 145–160.

Ciesinski, N.K. and Himelein-Wachowiak, M.K. (2023) ‘A systematic review with meta-analysis of cognitive bias modification interventions for anger and aggression’, Behaviour Research and Therapy, 164, 104305.

Deffenbacher, J.L. (2011) ‘Cognitive-behavioural conceptualization and treatment of anger’, Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 18(2), pp. 212–221.

Del Vecchio, T. and O’Leary, K.D. (2004) ‘Effectiveness of anger treatments for specific anger problems: A meta-analytic review’, Clinical Psychology Review, 24(1), pp. 15–34.

Eadeh, H.M., Breaux, R. and Nikolas, M.A. (2021) ‘A meta-analytic review of emotion regulation focused psychosocial interventions for adolescents’, Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 24, pp. 1–28.

Henwood, K.S., Chou, S. and Browne, K.D. (2015) ‘A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of CBT informed anger management’, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 25, pp. 280–292.

Howells, K. and Day, A. (2003) ‘Readiness for anger management: Clinical and theoretical issues’, Clinical Psychology Review, 23(2), pp. 319–337.

Larson, J. and Lochman, J.E. (2010) Helping schoolchildren cope with anger: A cognitive-behavioral intervention. New York: Guilford Press.

Lee, A.H. and DiGiuseppe, R. (2018) ‘Anger and aggression treatments: A review of meta-analyses’, Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, pp. 65–74.

Saini, M. (2009) ‘A meta-analysis of the psychological treatment of anger’, Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 37(4), pp. 473–488.

Shahsavarani, A.M., Noohi, S. and Heyrati, H. (2016) ‘Anger management and control in social and behavioural sciences: A systematic review’, International Journal of Medical Reviews, 3(1), pp. 1–12.

Sukhodolsky, D.G., Kassinove, H. and Gorman, B.S. (2004) ‘Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anger in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis’, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9(3), pp. 247–269.

Sukhodolsky, D.G. and Smith, S.D. (2016) ‘Behavioral interventions for anger, irritability, and aggression in children and adolescents’, Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(1), pp. 58–64.

Toohey, M.J. (2021) ‘Cognitive behavioral therapy for anger management’, in Encyclopedia of Cognitive Behavior Therapy. New York: Springer.