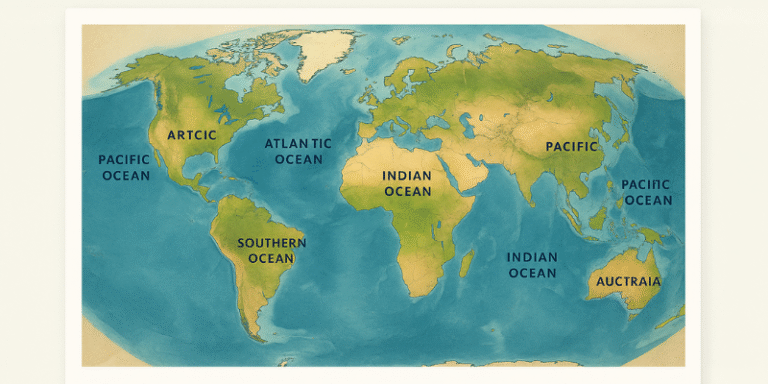

The Five Oceans: Earth’s Interconnected Marine Realms

The Earth’s surface is dominated by water, with oceans covering approximately 71% of the planet. These vast bodies of saltwater are typically divided into five major oceans: the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Southern (or Antarctic), and Arctic Oceans. While historically considered separate, these oceans are interconnected and form a single global ocean system. The classification of the five oceans is based on geographical, oceanographic, and geopolitical considerations. This article explores the characteristics, significance, and challenges facing each of the five oceans, with reference to scientific literature and authoritative sources.

1.0 The Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of the five oceans, spanning approximately 165 million square kilometres and reaching depths of over 11,000 metres in the Mariana Trench (National Geographic, 2024). Bounded by Asia and Australia on the west and the Americas on the east, the Pacific plays a central role in global climate regulation and weather patterns, particularly through the El Niño and La Niña phenomena.

The Pacific is also a key zone for tectonic activity. The “Ring of Fire,” a horseshoe-shaped area within the Pacific Basin, is home to about 75% of the world’s active volcanoes (Garrison, 2012). It is an area of significant seismic activity due to the movement of tectonic plates, resulting in frequent earthquakes and tsunamis.

In terms of marine biodiversity, the Pacific Ocean supports extensive coral reef systems, including the Great Barrier Reef, which is the largest reef system on Earth (Hughes et al., 2017). However, the Pacific is under threat from climate change, overfishing, and plastic pollution. Studies have highlighted the North Pacific Gyre, also known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, as a focal point for marine debris accumulation (Lebreton et al., 2018).

2.0 The Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest ocean, covering about 106 million square kilometres. It stretches from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south and is flanked by the Americas to the west and Europe and Africa to the east. Historically, the Atlantic has been of immense importance to global trade, exploration, and cultural exchange (Couper, 2008).

Ocean currents in the Atlantic, such as the Gulf Stream, have significant effects on the climate of adjacent continents. The thermohaline circulation, sometimes referred to as the global conveyor belt, plays a critical role in regulating Earth’s climate by redistributing heat and salinity (Talley, 2013).

Despite its historical and economic significance, the Atlantic faces numerous environmental challenges. Overfishing, oil spills, and habitat destruction threaten marine life. Furthermore, ocean acidification caused by increased carbon dioxide absorption is affecting shell-forming organisms and coral ecosystems (Doney et al., 2009).

3.0 The Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest ocean, encompassing around 70 million square kilometres. It is bounded by Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Southern Ocean. The Indian Ocean is unique for its relatively enclosed geography and monsoon-driven weather systems, which have shaped the climate and cultures of surrounding regions for centuries (Schott and McCreary, 2001).

This ocean is a vital corridor for global shipping and trade, particularly for oil transported from the Middle East to Asia. The region also hosts critical chokepoints such as the Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Malacca.

Marine biodiversity in the Indian Ocean is rich but under threat. Coral bleaching, illegal fishing, and marine pollution are pressing concerns. Additionally, the Indian Ocean has witnessed a rise in sea surface temperatures, which has been linked to changes in tropical cyclone patterns and intensities (Webster et al., 2005).

4.0 The Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, encircles the continent of Antarctica and extends to 60 degrees south latitude. It is the fourth-largest ocean and plays a vital role in the Earth’s climate system. The Southern Ocean drives the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, which is the world’s strongest ocean current and acts as a thermal barrier between Antarctica and the rest of the planet (Rintoul et al., 2001).

This ocean is crucial for deep ocean water formation, which is a key component of global thermohaline circulation. It is also a major sink for atmospheric carbon dioxide and heat, influencing global climate dynamics (Frölicher et al., 2015).

Despite its remote location, the Southern Ocean is increasingly affected by human activities. Climate change has led to warming waters and declining sea ice extent, which impact krill populations – a fundamental component of the Antarctic food web (Atkinson et al., 2004). Fishing pressures, especially for Patagonian toothfish and Antarctic krill, have prompted international regulatory measures through the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR, 2023).

5.0 The Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the five oceans, covering about 14 million square kilometres. It is located around the North Pole and is mostly covered by sea ice, although this coverage is diminishing rapidly due to climate change (Serreze and Meier, 2019).

The Arctic Ocean is bordered by North America, Europe, and Asia and is increasingly viewed as a region of geopolitical and economic interest due to emerging shipping routes and access to oil and gas reserves. The retreat of sea ice is making the Northwest Passage and Northern Sea Route more navigable during summer months.

However, the Arctic is also one of the most vulnerable environments on Earth. Rising temperatures have led to the loss of multi-year ice, threatening indigenous communities and Arctic biodiversity. Species such as polar bears, walruses, and narwhals are particularly at risk (Post et al., 2013).

The five oceans – Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Southern, and Arctic – are not only vast and dynamic bodies of water but are integral to life on Earth. They regulate the planet’s climate, support marine biodiversity, enable global trade, and provide food and livelihood for billions of people. However, each of these oceans faces mounting environmental threats driven by climate change, pollution, overexploitation, and geopolitical pressures.

A better understanding of the interconnectivity and unique features of each ocean is essential for their conservation. International cooperation, sustainable practices, and scientific research must be at the forefront of efforts to protect these vital global commons.

References

Atkinson, A. et al., 2004. Long-term decline in krill stock and increase in salps within the Southern Ocean. Nature, 432(7013), pp.100-103.

CCAMLR, 2023. Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. [online] Available at: https://www.ccamlr.org [Accessed 8 Jul. 2025].

Couper, A., 2008. The Shipping Revolution: The Modern Merchant Ship. London: Lloyd’s List.

Doney, S.C. et al., 2009. Ocean acidification: The other CO₂ problem. Annual Review of Marine Science, 1, pp.169-192.

Frölicher, T.L., Sarmiento, J.L., Dunne, J.P. and Paynter, D.J., 2015. Dominance of the Southern Ocean in Anthropogenic Carbon and Heat Uptake in CMIP5 Models. Journal of Climate, 28(2), pp.862-886.

Garrison, T., 2012. Oceanography: An Invitation to Marine Science. 8th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Hughes, T.P. et al., 2017. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature, 543(7645), pp.373–377.

Lebreton, L. et al., 2018. Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Scientific Reports, 8, pp.1–15.

National Geographic, 2024. Pacific Ocean. [online] Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com [Accessed 8 Jul. 2025].

Post, E. et al., 2013. Ecological consequences of sea-ice decline. Science, 341(6145), pp.519-524.

Rintoul, S.R. et al., 2001. Circulation and water masses of the Southern Ocean: A review. In: G. Siedler, J. Church and J. Gould, eds. Ocean Circulation and Climate. San Diego: Academic Press, pp.271–302.

Schott, F.A. and McCreary, J.P., 2001. The monsoon circulation of the Indian Ocean. Progress in Oceanography, 51(1), pp.1-123.

Serreze, M.C. and Meier, W.N., 2019. The Arctic’s Changing Climate. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Talley, L.D., 2013. Descriptive Physical Oceanography: An Introduction. 6th ed. London: Elsevier.

Webster, P.J. et al., 2005. Changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity in a warming environment. Science, 309(5742), pp.1844-1846.