University life is characterised by increased independence, critical thinking, and academic expectations. Among the most significant challenges faced by students is mastering the skill of academic assignment writing, which serves not only as a tool for assessment but also as a process that enhances learning and intellectual growth. Assignments require students to interpret briefs, plan effectively, structure arguments, and reference appropriately. Developing these skills contributes directly to academic success and long-term employability (Cottrell, 2013).

This article explores strategies for achieving success in assignment writing, including interpreting briefs, structuring responses, using feedback, applying reflective learning, and engaging with digital tools. It also highlights research findings that connect assignment writing practices with improved academic outcomes.

1.0 Interpreting an Assignment Brief

The assignment brief is a roadmap that guides students towards meeting their lecturer’s expectations. Misinterpreting it is a common cause of underperformance (Moon, 2004). Three key aspects are critical:

1.1 Command Words

Assignments contain verbs such as analyse, evaluate, compare, and discuss, which signal the cognitive level expected. According to Cottrell (2013), “analyse” requires breaking down concepts, while “evaluate” demands critical judgement based on evidence. Failure to understand these nuances can lead to superficial answers. Research by Al-Bayati (2025) highlights that students with stronger planning and monitoring skills are more successful at interpreting complex writing tasks.

1.2 Content

Understanding the theories, concepts, and frameworks required is equally important. As Yingbao et al. (2025) argue, effective academic writing demonstrates disciplinary knowledge while applying it to specific tasks. For example, an essay on leadership must reference core theories such as transformational leadership or situational leadership models to meet academic standards.

1.3 Context

Assignments are frequently framed within practical scenarios, such as case studies or workplace problems. Cottrell (2013) notes that students succeed when they explicitly connect theoretical knowledge to the practical context. For instance, a business student asked to apply Porter’s Five Forces to a real company must demonstrate awareness of market dynamics rather than offering generic explanations.

2.0 Structuring and Managing Assignments

2.1 Word Count and Organisation

Word counts are not arbitrary but reflect the scope of analysis required. The Purdue University Online Writing Lab (2024) advises dividing assignments into logical sections, each with a word allocation. A 2000-word essay, for example, may allocate 200 words to the introduction, 1400 to the main body (divided among subtopics), and 400 to the conclusion. This ensures balance and depth.

2.2 Time Management and Submission Deadlines

Time management is a recurring theme in academic success literature. Mittler (2025) stresses that tools such as AI-assisted planners can help students overcome procrastination and executive dysfunction. Planning ahead not only reduces stress but also allows revision and proofreading, which are critical for producing polished work (Moon, 2004).

2.3 Drafting and Revision

Writing is a process, not a product. Skorczewski and Nicholes (2025) show that students who draft, receive feedback, and revise achieve higher grades and deeper understanding of subject matter. Revisions allow for greater clarity, logical flow, and integration of evidence.

3.0 Types of Assessment

3.1 Formative Assessment

Formative tasks are intended to provide feedback without high stakes. These may include short essays, presentations, or peer reviews. Brown et al. (2025) demonstrate that transparent formative feedback through frameworks such as TILT (Transparency in Learning and Teaching) leads to measurable improvements in writing quality.

3.2 Summative Assessment

Summative assessments, such as final essays and reports, carry weight in overall grades. Unlike formative tasks, they are final submissions. Therefore, students must ensure that their arguments are well supported, references are accurate, and the structure aligns with academic conventions (Moon, 2004).

4.0 Developing Strong Writing Skills

4.1 Academic Style and Language

Assignments require formal, objective, and concise writing. According to Hrdličková (2025), integrating writing strategies with digital tools helps students refine their tone and grammar. For example, tools like citation managers reduce referencing errors, while grammar checkers enhance clarity.

4.2 Critical Thinking and Argumentation

Successful assignments do not merely describe but critically evaluate. Liu et al. (2025) argue that critical writing demonstrates reasoning, synthesis, and the ability to engage with multiple perspectives. For example, a sociology essay comparing Marxist and functionalist views should not only summarise theories but also evaluate their relevance in contemporary society.

4.3 Referencing and Academic Integrity

Proper referencing avoids plagiarism and demonstrates engagement with scholarly work. Universities typically adopt referencing styles such as Harvard or APA. As Nasir et al. (2025) note, mastering referencing systems builds confidence and enhances credibility.

5.0 Using Feedback Effectively

Feedback is a valuable but often underutilised tool. Students sometimes view it as criticism rather than a pathway to improvement. Lazareva and Muhic (2025) show that students who actively apply feedback strategies—such as noting recurring issues in structure or citation—demonstrate consistent academic growth.

For example, a lecturer’s note to “develop analysis further” should prompt the student to add critical commentary on sources rather than extending descriptions. Over time, applying feedback develops self-regulated learning habits.

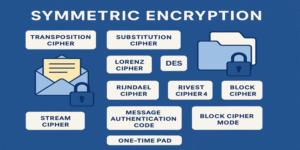

6.0 The Role of Technology in Assignment Success

Digital tools play an increasingly central role in academic writing. Van Scooter (2025) highlights that hybrid and online learning environments require new approaches to structuring and presenting assignments. AI-supported tools can help with task organisation, language refinement, and citation accuracy (Mittler, 2025).

However, as Pedersen (2025) warns, overreliance on generative AI may undermine students’ critical and creative skills. Therefore, such tools should be viewed as aids, not replacements, for independent academic thought.

7.0 Reflective Learning and Continuous Improvement

Moon (2004) emphasises the importance of reflective practice in assignment writing. Students who reflect on previous assignments, identifying strengths and weaknesses, are more likely to succeed in future tasks. Saykova (2025) confirms that personalised reflection pathways, particularly in language learning, significantly improve academic writing outcomes.

Assignment writing is both an assessment tool and a learning process. Success depends on accurately interpreting briefs, managing time effectively, structuring responses, and applying feedback. Incorporating critical thinking, formal style, and proper referencing ensures assignments meet academic standards. Furthermore, using technology responsibly and adopting reflective practices fosters continuous improvement.

By combining these strategies, students can not only achieve higher grades but also develop essential skills for professional and lifelong success.

References

Al-Bayati, Z.A.A. (2025). The Interrelationship of Planning, Monitoring, and Evaluation as High-Order Executive Skills on EFL University Students’ Writing Performance. University of Mustansiriyah. Available at: https://iasj.rdd.edu.iq/journals/uploads/2025/07/14/07023ac1d147c037a19bccdcc8743960.pdf.

Brown, E.A., Kronenburg, M. & Steeley, A. (2025). A Case Study Using the Transparency Framework and Artificial Intelligence to Promote Effective Writing and Student Success. Journal of Health Administration Education, 41(2).

Cottrell, S. (2013). The Study Skills Handbook. 4th ed. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hrdličková, Z. (2025). Enhancing Learning Outcomes in Written Production by Implementing Writing Strategies and Using AI Tools. Advanced Education Journal, 13(1), pp. 45–58.

Lazareva, A. & Muhic, M. (2025). University Students’ Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools in Their Studies. EDULEARN25 Proceedings.

Liu, O.L., Song, Y. & Wang, Y. (2025). Fostering Student Critical Thinking in Postsecondary Education. Springer.

Mittler, S. (2025). Harnessing Generative AI to Overcome Executive Dysfunction in Higher Education. HEAD Conference Proceedings.

Moon, J. A. (2004). A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning: Theory and Practice. Routledge.

Nasir, N.A.M., Yaacob, N.H. & Razaki, M. (2025). The Road to MUET Speaking Mastery. Journal of Nusantara Studies, 10(2), pp. 33–50.

Pedersen, I. (2025). AI Agents, Wearable Computing and the Future of Postsecondary Learning. Frontiers in Education, 10, pp. 1–12.

Purdue University Online Writing Lab (2024). Understanding Writing Assignments. Available at: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/understanding_writing_assignments.html [Accessed 30 July 2024].

Saykova, M. (2025). Aspects of Medical College Students’ Opinions of the Role of Digital Platforms. Knowledge International Journal, 52(3), pp. 75–88.

Skorczewski, T. & Nicholes, J. (2025). Writing to Engage in Multivariate Calculus. Across the Disciplines, 22(1).

Yingbao, L., Ismail, H.H.B. & Yunus, M.M. (2025). Needs Analysis for Enhancing Academic English Writing Instruction. International Journal of Academic Research in Education.

Van Scooter, B. (2025). Better Practices: Teaching Writing in Online and Hybrid Spaces. University Press of Colorado.