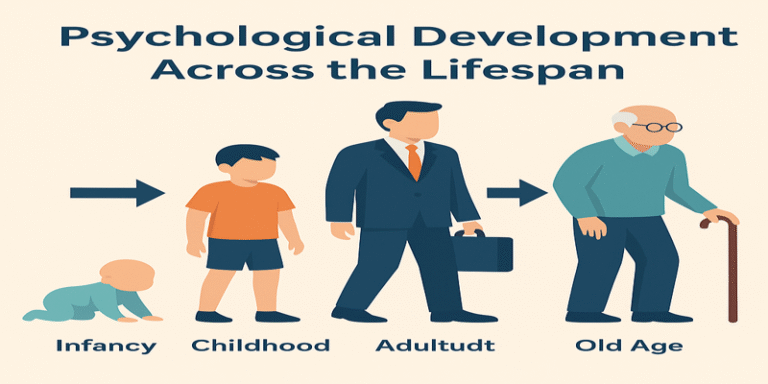

Human psychological development is a lifelong process that involves continuous changes in physical, emotional, social, and cognitive domains. Psychologists and developmental theorists have long examined how individuals evolve from infancy through old age, identifying critical milestones and transformations that influence behaviour, identity, and functioning. Understanding these developmental changes is vital not only in psychology but also in education, healthcare, and social work.

1.0 Infancy and Early Childhood: Foundation of Development

Infancy marks the beginning of psychological development. During this period, physical growth is rapid. Infants develop motor skills, such as crawling and grasping, which in turn influence their social and cognitive engagement with the world (Berk, 2022). Emotional development begins with attachment formation—usually with primary caregivers—which sets the stage for later emotional regulation and social bonding (Bowlby, 1969).

Cognitively, Jean Piaget described early childhood as the sensorimotor and preoperational stages, wherein children begin to develop memory, object permanence, and symbolic thought (Piaget, 1952). Social development during these years centres around learning to trust others, interact with peers, and develop basic communication skills.

“The quality of attachment relationships in infancy influences not only emotional stability but also cognitive and social competencies later in life” (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019, p. 42).

2.0 Middle Childhood: Cognitive and Social Expansion

By middle childhood (6–12 years), physical development slows compared to infancy but becomes more coordinated. Children refine motor skills and become increasingly independent. Emotionally, they learn to regulate feelings and begin to understand complex emotions like guilt and empathy (Riediger & Bellingtier, 2022).

Cognitive development is characterised by concrete operational thinking. According to Piaget, children at this stage can perform mental operations on concrete objects, leading to improved logical reasoning and problem-solving skills (Sigelman et al., 2018). Socially, peer interactions become vital. Friendships are based on mutual interests, and children start to understand societal norms and rules.

“The school environment becomes a crucial context for social and cognitive development, encouraging cooperative behaviours and perspective-taking” (Peterson, 2013, p. 161).

3.0 Adolescence: Identity and Abstract Thought

Adolescence is marked by significant pubertal changes that affect self-concept and social dynamics. Teenagers grapple with identity, autonomy, and peer pressure, as outlined in Erikson’s stage of identity vs. role confusion (Erikson, 1968). Emotional regulation becomes more complex, with increased risk for mental health challenges such as anxiety and depression.

Cognitively, adolescents transition into formal operational thinking, allowing abstract reasoning and hypothetical thinking (Berk, 1998). This enables them to consider future possibilities and moral dilemmas. Socially, they become more influenced by peer groups than family and start to explore romantic relationships.

“Neurodevelopmental changes in the adolescent brain support both the advancement of executive functions and increased sensitivity to social stimuli” (Craik & Bialystok, 2006, p. 133).

4.0 Early Adulthood: Independence and Intimacy

In early adulthood (20s–30s), individuals typically experience peak physical health and cognitive performance. However, this stage also involves navigating complex emotional landscapes such as intimate relationships, career commitments, and establishing independence. Erikson termed this stage intimacy vs. isolation, where success leads to strong relationships and failure may result in loneliness.

Emotionally and socially, adults learn to balance love, work, and personal goals. They continue refining self-concepts and emotional regulation skills. Cognitively, while fluid intelligence (problem-solving) may peak, crystallised intelligence (knowledge accumulated over time) starts to play a larger role in decision-making (Baltes & Staudinger, 1999).

“Adulthood is less about acquiring new skills and more about integrating and applying existing competencies across domains of life” (Wu, Rebok & Lin, 2017, p. 345).

5.0 Middle Adulthood: Stability and Generativity

Middle adulthood (40s–60s) typically features physical ageing, such as reduced strength and slower metabolism. While cognitive decline may begin in specific areas, many adults compensate with experience and insight. Emotionally, individuals often achieve greater stability and self-acceptance.

Erikson proposed generativity vs. stagnation as the central conflict—adults seek to contribute to society through parenting, work, and mentoring. Socially, relationships may deepen, and individuals reevaluate life goals and achievements (Cole & O’Hanlon, 2017).

“Midlife is characterised by a paradoxical blend of growth and loss—people refine their emotional responses while acknowledging emerging physical limitations” (Charles & Carstensen, 2003, p. 174).

6.0 Late Adulthood: Reflection and Adaptation

Late adulthood (65+) brings pronounced physical decline and increased vulnerability to illness. Cognitive changes are varied: while some older adults face memory loss or dementia, others retain cognitive functioning and even show growth in wisdom (Baltes, 1987).

Emotionally, older adults often demonstrate resilience and prioritise emotionally meaningful relationships, as explained by Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (Carstensen, 2010). Erikson’s final stage—integrity vs. despair—focuses on reflecting on life with satisfaction or regret.

Social engagement often declines due to retirement, bereavement, or reduced mobility, yet many older adults adapt through community involvement or intergenerational relationships (Labouvie-Vief, 2015).

“Emotional functioning in older age often becomes more refined, characterised by acceptance, emotional clarity, and reduced reactivity” (Charles & Carstensen, 2010, p. 396).

Psychological development across the human lifespan is an intricate interplay of physical, emotional, social, and cognitive transformations. From the dependent infancy stage to reflective old age, humans continue to adapt and evolve. While developmental stages provide a useful framework, individual variability ensures that no two developmental journeys are exactly alike. Recognising this complexity is essential for supporting people at every life stage, whether through education, healthcare, or community engagement.

References

Baltes, P.B. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23(5), 611–626. https://www.imprs-life.mpg.de/25277/022_baltes_1987.pdf

Baltes, P.B., & Staudinger, U.M. (1999). Lifespan psychology: Theory and application to intellectual functioning. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 471–507. https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.471

Berk, L.E. (1998). Development Through the Lifespan. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Berk, L.E. (2022). Exploring Lifespan Development. London: Pearson Education.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Volume I. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Carstensen, L.L., & Charles, S.T. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383–409. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3950961/pdf/nihms554974.pdf

Charles, S.T., & Carstensen, L.L. (2003). A life span view of emotional functioning in adulthood and old age. Advances in Cell Aging and Gerontology, 15, 133–162. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1566312403150055

Cole, P.G., & O’Hanlon, A. (2017). Aging and Development: Social and Emotional Perspectives. London: Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315726946

Craik, F.I.M., & Bialystok, E. (2006). Cognition through the lifespan: Mechanisms of change. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(3), 131–138. https://www.cell.com/trends/cognitive-sciences/fulltext/S1364-6613(06)00022-2

Erikson, E.H. (1968). Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton.

Labouvie-Vief, G. (2015). Integrating Emotions and Cognition Throughout the Lifespan. Cham: Springer. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-319-09822-7.pdf

Lally, M., & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective. ScholarWorks. https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/v118rn28j

Peterson, C.C. (2013). Looking Forward Through the Lifespan: Developmental Psychology. Sydney: Pearson Australia.

Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International Universities Press.

Riediger, M., & Bellingtier, J.A. (2022). Emotion Regulation Across the Lifespan. In: Handbook of Emotional Development. London: Routledge.