Toddlerhood, typically defined as the period between a child’s first and third birthday, is one of the most remarkable stages of human development. In these short but intense years, children transition from dependent infants to increasingly independent and expressive young individuals. Their rapid growth and developmental milestones span physical, cognitive, emotional, and social domains, laying the foundation for future learning and relationships.

Physical Development

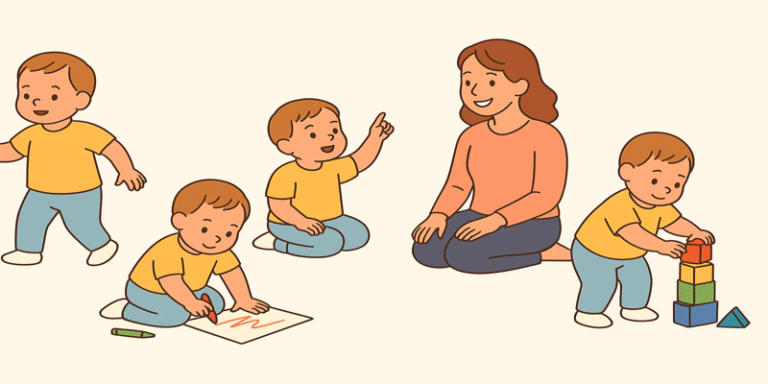

By the age of one, most toddlers have mastered standing with support and are beginning to take their first independent steps. Gross motor skills—the abilities involving large muscle groups—progress swiftly during toddlerhood. By around 18 months, children can walk steadily, squat to pick up objects, and begin to climb onto low furniture (Colson & Dworkin, 1997). By age two, they can run, kick a ball, and pull toys while walking, and by age three, many can pedal a tricycle and walk up and down stairs using alternating feet (Lissauer & Carroll, 2017).

Fine motor skills also advance, enabling toddlers to feed themselves with a spoon, build towers of blocks, and turn pages in a book. At around 18 months, many can scribble with crayons, and by age three, they may draw simple shapes (Burns, 2019).

Cognitive Development

Cognitively, toddlers are in Piaget’s sensorimotor stage moving into the preoperational stage (Piaget, 1952). They begin to understand object permanence fully and engage in symbolic play, where an object represents something else—like using a block as a pretend phone. By around age two, problem-solving skills improve, with toddlers experimenting and learning through trial and error (Reigstad, 2024).

Language acquisition accelerates during this period. A one-year-old might say a handful of words, but by age two, toddlers typically have vocabularies of 50–100 words and begin forming two-word sentences (Scharf, Scharf & Stroustrup, 2016). By the third birthday, many can speak in three- to four-word sentences, ask simple questions, and understand basic grammar rules.

Emotional and Social Development

Emotionally, toddlerhood is a time of self-discovery and autonomy. Erikson (1963) identified the psychosocial stage of autonomy versus shame and doubt for this age group. Toddlers begin to assert their independence—often with the famous “No!”—and seek to do things on their own, from choosing clothes to attempting self-feeding (Edwards & Liu, 2005).

Attachment remains important, with toddlers looking to caregivers for comfort and security, especially in unfamiliar situations. However, they also start to explore parallel play, where they play alongside, but not yet with, other children (Lieberman, Barnard & Plemmons, 2004). By age three, more interactive play and sharing behaviours begin to emerge.

Language and Communication Milestones

Language growth is one of the most striking features of toddlerhood. According to developmental guidelines, a 12-month-old can typically follow simple one-step commands like “Come here.” By 24 months, toddlers can follow two-step directions, and their understanding of words far exceeds their spoken vocabulary (Tomopoulos et al., 2006). Exposure to reading, storytelling, and rich verbal interaction supports this rapid expansion.

Socialisation and Play

Play is the central occupation of toddlers, fostering motor, cognitive, and social skills. In the early part of toddlerhood, play is mostly solitary or parallel, but by the third year, it evolves into associative play, where children start to share materials and engage in joint activities (Flavin et al., 2006). Play with blocks, puzzles, and pretend cooking sets not only entertains but also develops problem-solving and fine motor coordination.

Nutrition and Health

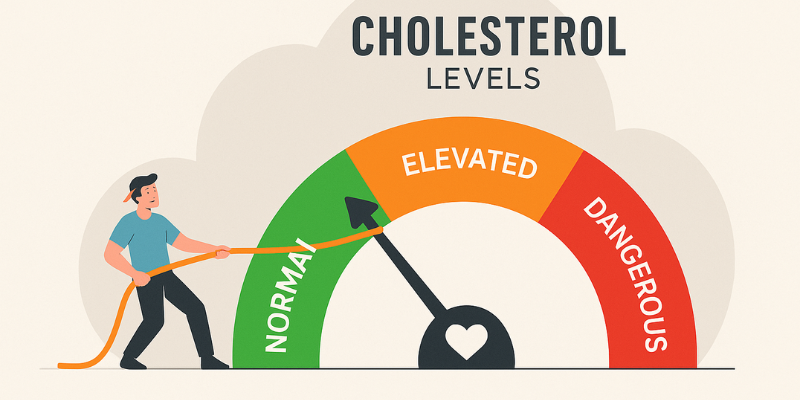

Nutrition plays a vital role in supporting development. Toddlers require a balanced diet rich in iron, calcium, and vitamins to sustain their rapid growth (Carruth et al., 2004). During this period, self-feeding skills improve, although picky eating can be common. Regular well-child visits help monitor growth patterns and developmental milestones, allowing early detection of potential delays (Halfon & Regalado, 2001).

Safety Considerations

With increased mobility comes increased risk. Toddlers are naturally curious and may climb, explore, or put small objects in their mouths. Accident prevention—through childproofing homes, supervising play, and teaching basic safety rules—is essential. For example, poisoning risks from adult medication are significantly higher in toddlers than in older children (Flavin et al., 2006).

Red Flags for Developmental Concerns

While development varies greatly between children, some signs may warrant further assessment. For instance, a child who is not walking by 18 months, not speaking at least 15 words by two years, or showing no interest in interaction by three years may benefit from developmental screening (Johnson-Martin, Attermeier & Hacker, 2004).

Toddlerhood is a dynamic and transformative period in a child’s life. These years bring enormous strides in physical skills, cognitive abilities, and social-emotional understanding. Recognising developmental milestones helps caregivers, educators, and health professionals support children’s individual growth paths while identifying those who may need additional assistance. The experiences and support provided in toddlerhood can have a profound impact on a child’s future learning, relationships, and overall well-being.

References

Burns, V. (2019) Development of Early Childhood Physical Development. In: Burns’ Paediatric Primary Care E-Book. Elsevier.

Carruth, B.R., Ziegler, P.J., Gordon, A. and Hendricks, K. (2004) ‘Developmental milestones and self-feeding behaviors in infants and toddlers’, Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 104(1), pp. 51–56.

Colson, E.R. and Dworkin, P.H. (1997) ‘Toddler development’, Pediatrics in Review, 18(7), pp. 227–234. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/dbpeds/ToddlerDvt.pdf

Edwards, C.P. and Liu, W. (2005) ‘Parenting toddlers’. In: Bornstein, M.H. (ed.) Handbook of Parenting. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 45–72.

Flavin, M.P. et al. (2006) ‘Stages of development and injury patterns in the early years: a population-based analysis’, BMC Public Health, 6(187). doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-187

Halfon, N. and Regalado, M. (2001) ‘Primary care services promoting optimal child development from birth to age 3 years: review of the literature’, Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 155(12), pp. 1311–1322.

Johnson-Martin, N., Attermeier, S.M. and Hacker, B.J. (2004) The Carolina Curriculum for Infants and Toddlers with Special Needs. 2nd edn. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing.

Lieberman, A.F., Barnard, K.E. and Plemmons, D. (2004) ‘Diagnosing infants, toddlers and preschoolers’. In: Handbook of Infant, Toddler, and Preschool Mental Health. New York: Guilford Press.

Lissauer, T. and Carroll, W. (2017) Illustrated Textbook of Paediatrics. 5th edn. Elsevier.

Piaget, J. (1952) The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International Universities Press.

Reigstad, B. (2024) Module 5: Infancy and Toddlerhood Development. Minnesota Libraries Publishing Project. Available at: https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/humandevelopment/chapter/module-5-infancy-toddlerhood-development/

Scharf, R.J., Scharf, G.J. and Stroustrup, A. (2016) ‘Developmental milestones’, Pediatrics in Review, 37(1), pp. 25–37.

Tomopoulos, S. et al. (2006) ‘Books, toys, parent–child interaction, and development in young Latino children’, Ambulatory Pediatrics, 6(2), pp. 72–78.