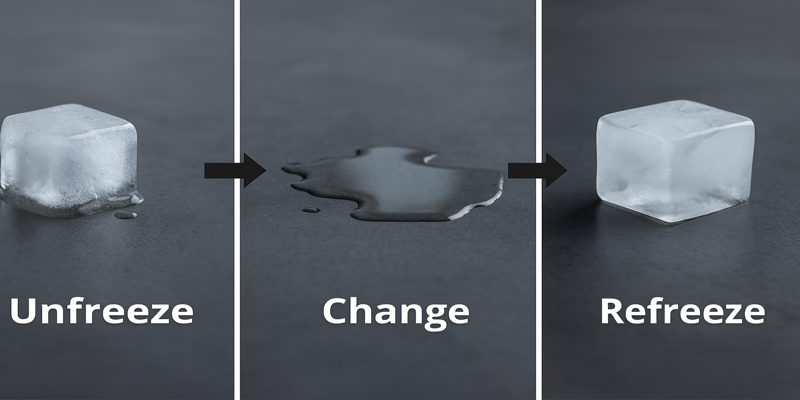

Lewin’s Change Management Model: Framework for Modern Transformation

Change management is one of the most critical disciplines in modern organisational practice, especially as businesses and institutions face constant pressures from technological disruption, globalisation, and sustainability imperatives. Among the various frameworks available, Kurt Lewin’s Change Management Model (1951) stands out as one of the most influential and enduring. Despite its simplicity, the model continues to provide managers and leaders with a powerful framework for guiding organisational transformation. The model consists of three distinct stages: Unfreeze, Change, and Refreeze. These phases help organisations prepare for, implement, and consolidate new practices. While originally conceptualised in the mid-20th century, the framework remains relevant in contexts such as digital transformation, healthcare innovation, and cultural change programmes (Burnes, 2017; Gloria, 2025). 1.0 The Unfreeze Stage: Preparing for Change The Unfreeze stage focuses on preparing individuals and organisations for transformation by breaking down existing practices, assumptions, and behaviours. Lewin (1951) described this as a process of destabilising the status quo, making people receptive to change. Key activities in this stage include: Communicating the urgency for change. Identifying and addressing potential resistance. Building a compelling vision for the future. Burnes (2017) emphasises that unfreezing requires leaders to create a sense of discomfort with current practices while presenting a positive alternative. For example, in the financial services industry, the adoption of stricter post-crisis regulations involved “unfreezing” by showing the risks of previous practices and the benefits of compliance and transparency. Recent research demonstrates its applicability in sustainable industries. Gloria (2025) found that unfreezing through vision-building and stakeholder engagement was essential for implementing agile and resilient manufacturing processes. Similarly, Nababan and Girsang (2024) argue that unfreezing organisational culture is critical for developing digital communication strategies in retail. 2.0 The Change Stage: Transition and Implementation Once readiness is achieved, the Change stage involves transitioning towards new behaviours, processes, or structures. This stage often generates uncertainty and anxiety among employees, as familiar ways of working are replaced with the unknown. Key activities in this stage include: Providing training and development opportunities. Ensuring clear and consistent communication. Demonstrating leadership support and modelling new behaviours. Rajapakshe (2025), in a study of mergers and acquisitions in Sri Lanka’s telecommunications industry, highlights that leadership visibility and human resource practices such as training and mentoring were critical to the successful transition. Without adequate support, employees may disengage or resist the process. In healthcare, Mugge et al. (2024) demonstrated that ICT adoption for circular economy initiatives succeeded during the change stage only when empathy and tailored resources were provided. Similarly, McMahon et al. (2024) emphasise the importance of structured change activities for digital sustainability initiatives. 3.0 The Refreeze Stage: Embedding Change The final stage, Refreeze, ensures that changes are institutionalised and embedded in the organisational culture. Without this consolidation, employees may revert to old habits, undermining the change effort (Lewin, 1951). Key activities include: Reinforcing new practices through incentives and recognition. Aligning organisational culture and structures with new behaviours. Monitoring progress and celebrating milestones. Burnes (2017) stresses that refreezing is essential for stability. In healthcare, for instance, the adoption of digital medical records only became successful once staff training and leadership reinforcement were institutionalised. Rajapakshe (2025) similarly notes that in post-merger integration, the refreezing stage is critical for aligning cultural practices across merged entities. Without reinforcement, employees may continue to identify with legacy structures rather than the new organisational identity. Applications of Lewin’s Model in Modern Contexts a) Digital Transformation Lewin’s model has been applied in Industry 4.0 environments. Hedberg and Thelander (2025) show that aircraft manufacturers used unfreeze-change-refreeze cycles to coordinate digital transformation projects. While unfreezing addressed legacy system inertia, refreezing involved embedding digital tools into everyday work practices. b) Organisational Culture Change Nababan and Girsang (2024) demonstrated that cultural transformation in Indonesian retail required unfreezing deep-seated practices before shifting to new communication strategies. Refreezing ensured these practices became embedded in team norms. c) Sustainability and Circular Economy McMahon et al. (2024) applied Lewin’s model to circular economy transitions in ICT. The unfreezing process involved highlighting environmental risks of existing practices, while refreezing reinforced sustainability behaviours through corporate policies. Critiques of Lewin’s Model Despite its continued relevance, Lewin’s model faces several criticisms: Oversimplification of change: Modern organisations face continuous, non-linear transformations, which do not neatly follow a three-stage cycle (Memana, 2025). Rigidity: The model may be less effective in highly dynamic industries where change is constant. Hedberg and Thelander (2025) argue that iterative and agile approaches are often required. Cultural limitations: In contexts with strong cultural inertia, unfreezing may require longer, multifaceted efforts, which Lewin’s model underplays. Nevertheless, many scholars argue that the model’s simplicity is also its strength. It provides an accessible foundation that can be adapted or integrated with other frameworks, such as Kotter’s 8-Step Process or ADKAR (Gómez Cortés & Ramirez Orozco, 2025). Strengths of Lewin’s Model Clarity and simplicity: Provides a straightforward roadmap for leaders and managers. Foundation for modern models: Many subsequent frameworks are built upon Lewin’s concepts. Focus on behaviour and culture: Recognises that sustainable change requires not only structural adjustments but also cultural embedding. Towards a Hybrid Approach Recent research suggests that organisations benefit from hybridising Lewin’s model with contemporary frameworks. For example: Kotter’s urgency-building and coalition strategies can enhance the unfreeze stage. ADKAR’s reinforcement focus can strengthen the refreeze stage. Agile methods can supplement the change stage to manage continuous adaptation (Hedberg & Thelander, 2025). By blending Lewin’s foundational principles with modern adaptations, organisations can achieve transformation that is both structured and flexible. Lewin’s Change Management Model remains a cornerstone of organisational change theory. Its three stages—Unfreeze, Change, and Refreeze—provide a simple yet powerful framework for guiding transformation. While critics argue that it may oversimplify today’s complex, non-linear environments, the model’s enduring relevance lies in its adaptability. In contexts ranging from mergers and acquisitions to digital transformation and sustainability, Lewin’s framework continues to guide leaders in navigating resistance, supporting transitions, and embedding cultural change. For sustainable transformation, the model works best when combined with modern approaches that account for iterative and continuous change. As organisations continue … Read more