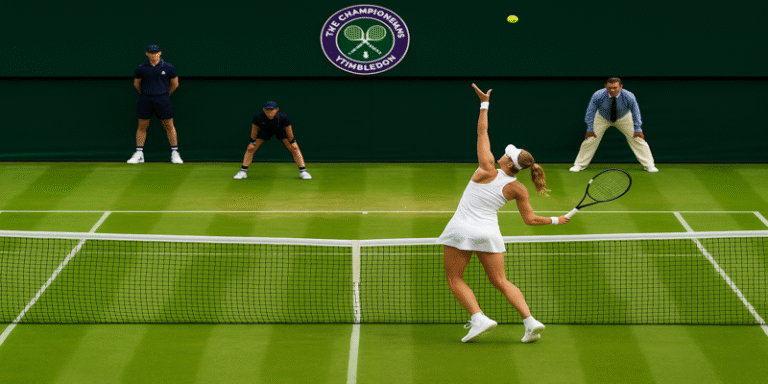

Wimbledon, officially known as The Championships, Wimbledon, is the world’s oldest and arguably most prestigious tennis tournament. Held annually in London since 1877, it is one of the four Grand Slam events and is renowned not just for its tennis but also for its deeply ingrained traditions, including its grass courts, all-white dress code, and the consumption of strawberries and cream. While tradition remains at its core, Wimbledon has also embraced innovation, adapting to modern demands without losing its unique identity.

Historical Background and Significance

Wimbledon began in 1877, organised by the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club (AELTC), initially as a men’s singles event. The first tournament attracted just 22 players and a few hundred spectators (Barrett, 2014). Over time, it expanded to include women’s singles in 1884 and eventually all major tennis categories. As a historical marker, Wimbledon stands out not just as a sporting event but as a cultural institution that has mirrored and influenced British society for nearly 150 years.

According to Lake (2015), the tournament’s persistence and popularity stem from its strong adherence to tradition, coupled with a strategic evolution in response to changes in sport and society. The use of grass courts, the original surface for tennis, is now unique among Grand Slam tournaments, with others shifting to hard and clay surfaces for ease of maintenance and playability.

Traditions and Cultural Identity

Wimbledon’s identity is deeply intertwined with British cultural values such as etiquette, class structure, and decorum. The strict all-white dress code, still enforced today, is a vestige of Victorian ideals of modesty and cleanliness (Berman, 2018). This adherence to tradition sets Wimbledon apart and contributes to its aura of prestige and exclusivity.

Another key tradition is the Royal Box, where members of the British Royal Family and other dignitaries are seated, symbolising the event’s elevated social status. The consumption of strawberries and cream, a simple yet iconic ritual, further reinforces the tournament’s British identity and nostalgic appeal (BBC Sport, 2021).

Organisational Structure and Economics

The All England Club oversees the management of Wimbledon and has historically maintained a cautious approach to commercialisation. Nevertheless, Wimbledon is a major global sporting enterprise, generating significant revenue from broadcasting rights, sponsorship, and ticket sales. In 2023, prize money reached a record £44.7 million, highlighting the tournament’s commercial success (Wimbledon, 2023).

Despite its conservative image, Wimbledon has made several modern adjustments. For example, retractable roofs were introduced to address the unpredictability of British weather, and equal prize money for men and women was implemented in 2007—trailing behind the US Open, which made the move in 1973 (Lopiano, 2000).

Technology and Innovation

Wimbledon has increasingly embraced technology to improve both player experience and audience engagement. The Hawk-Eye system, introduced in 2006, allows players to challenge line calls, enhancing the fairness of matches. Data analytics is also widely used by coaches and broadcasters to assess player performance and enrich viewer experience (O’Donoghue & Ingram, 2001).

Digital transformation has also played a major role in how Wimbledon reaches a global audience. In partnership with IBM, the tournament uses artificial intelligence to generate highlights, personalise digital content for fans, and optimise its official website and app experience (IBM, 2023). Such integration of cutting-edge technology ensures Wimbledon remains globally relevant without losing its traditional charm.

Gender, Equity and Representation

Wimbledon has long been critiqued for gender imbalances, particularly around prize money, match scheduling, and media representation. Although equal prize money is now a norm, disparities remain in less quantifiable areas. Research by Vincent and Kian (2014) shows that media narratives surrounding female players often focus more on appearance and personal life than athletic achievement.

Recent efforts to highlight female champions, such as dedicating Centre Court anniversaries to women and improving scheduling equity, mark positive steps. However, scholars like Claringbould and Knoppers (2012) argue that true gender equity in sport requires continuous attention to systemic bias, not just surface-level changes.

Globalisation and Wimbledon’s International Appeal

Wimbledon’s prestige has only grown with globalisation. International players like Roger Federer, Serena Williams, Novak Djokovic, and Iga Świątek have elevated its global status. Federer’s eight Wimbledon titles, in particular, have cemented his place as a tournament legend and increased the event’s viewership in markets like Switzerland and across Europe (Bowers, 2020).

Broadcast globally in over 200 countries, Wimbledon commands a viewership in the hundreds of millions. This international appeal has led to growing cultural intersections, with players bringing their own rituals and styles to the historically conservative tournament. Yet, Wimbledon carefully curates its brand to retain its British identity amidst global influence.

Sustainability and Future Directions

Environmental sustainability has become an area of increasing focus. The AELTC has committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2030. Initiatives include using electric vehicles, reducing single-use plastics, and implementing sustainable sourcing for food and materials (Wimbledon, 2022).

Looking ahead, Wimbledon faces the challenge of remaining traditional while responding to evolving societal values, technological innovation, and environmental responsibility. Its ability to blend these seemingly contradictory demands may determine its continued success.

Wimbledon Tennis is far more than a sporting event; it is a symbol of tradition, excellence, and gradual yet strategic modernisation. With its roots in Victorian England, Wimbledon has evolved to become a global spectacle that still cherishes its unique heritage. The tournament’s ability to honour the past while embracing the future serves as a model not just for tennis but for sports organisations worldwide.

References

Barrett, J. (2014) Wimbledon: The Official History. London: Vision Sports Publishing.

BBC Sport (2021) ‘Wimbledon: Why Strawberries and Cream are a Tradition’. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/sport/tennis/57581763 [Accessed 10 July 2025].

Berman, M. (2018) ‘Dress Codes and Identity: The Case of Wimbledon’. Sport in Society, 21(5), pp. 631–648.

Bowers, M.T. (2020) ‘Global Icons and National Identity in Sport: The Case of Roger Federer at Wimbledon’. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 44(2), pp. 134–150.

Claringbould, I. and Knoppers, A. (2012) ‘Paradoxical Practices of Gender in Sport-related Organisations’. Journal of Sport Management, 26(5), pp. 404–416.

IBM (2023) ‘Wimbledon and IBM: Digital Innovation in Sports’. Available at: https://www.ibm.com/sports/wimbledon [Accessed 9 July 2025].

Lake, R.J. (2015) A Social History of Tennis in Britain: 1874–1914. London: Routledge.

Lopiano, D.A. (2000) ‘Modernising Equality: Grand Slams and Gender Pay’. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 9(2), pp. 25–34.

O’Donoghue, P. and Ingram, B. (2001) ‘A Notational Analysis of Elite Tennis Strategy’. Journal of Sports Sciences, 19(2), pp. 107–115.

Vincent, J. and Kian, E. (2014) ‘Sport, Media and Gender: Coverage of Female Tennis Players’. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 49(3–4), pp. 331–346.

Wimbledon (2022) ‘Sustainability Strategy’. Available at: https://www.wimbledon.com/en_GB/atoz/sustainability.html [Accessed 10 July 2025].

Wimbledon (2023) ‘Prize Money Announced for 2023 Championships’. Available at: https://www.wimbledon.com/en_GB/news/articles/2023-06-15 [Accessed 10 July 2025].