Organisational structure is a fundamental aspect of business management, defining how tasks are divided, coordinated, and supervised within an organisation. The structure an organisation adopts is influenced by its size, scope, and strategic objectives. Over time, different types of structures have evolved, ranging from traditional bureaucratic models to more contemporary, flexible forms that cater to the complexities of modern global business environments.

1.0 Traditional Organisational Structures

1.1 Bureaucratic Structure

The bureaucratic structure is one of the most traditional forms of organisational design, typically characterised by a hierarchical setup with clear lines of authority and a well-defined chain of command. This structure is highly formalised, with strict rules, procedures, and a clear division of labour. Bureaucratic structures are often found in large, established organisations where stability and efficiency are priorities (Weber, 1947).

While this structure offers clear advantages in terms of order and predictability, it can also be criticised for its rigidity and slow response to change. In today’s fast-paced business environment, bureaucratic structures may hinder innovation and adaptability, making them less suitable for dynamic industries.

1.2 Post-Bureaucratic Structure

As a response to the limitations of the bureaucratic model, post-bureaucratic structures have emerged. These structures are more flexible and decentralised, allowing for greater autonomy at different levels of the organisation. Decision-making is often more collaborative, and there is an emphasis on teamwork and shared responsibility (Heckscher, 1994).

Post-bureaucratic structures are more adaptive to change, fostering innovation and employee engagement. However, they can also present challenges in terms of consistency and control, particularly in larger organisations where coordination across different units is essential.

2.0 Organisational Structures Based on Size and Scope

2.1 Parent and Strategic Business Units (SBUs)

Large corporations often adopt a parent and SBUs structure, particularly when they operate in multiple industries or regions. The parent organisation holds overarching control and provides strategic direction, while SBUs operate semi-autonomously, focusing on specific markets, products, or services (Prahalad & Doz, 1987).

This structure allows for greater focus and specialisation at the SBU level, while still maintaining strategic alignment with the overall objectives of the parent organisation. However, managing multiple SBUs can be complex, requiring effective communication and coordination to avoid conflicts and ensure synergies are realised.

2.2 Matrix Structure

The matrix structure is another approach used by organisations that operate in diverse environments. It is a hybrid structure that combines functional and product-based divisions, creating a grid-like system where employees report to both functional and product managers (Davis & Lawrence, 1977).

This structure allows organisations to leverage the benefits of specialisation while remaining flexible and responsive to different market needs. However, it can also lead to confusion and conflicts in authority, as employees may receive conflicting directives from different managers.

2.3 Functional Structure

In a functional structure, the organisation is divided into departments based on specialised functions such as marketing, finance, human resources, and operations. Each department is headed by a functional manager who oversees its activities and reports to the top management (Mintzberg, 1979).

This structure is efficient for organisations with a narrow product focus and stable environments. It allows for economies of scale and deep expertise within each function. However, it can also create silos, leading to poor communication and coordination between departments.

3.0 The Virtual Organisation and Flexible Structures

3.1 Virtual Organisation

The rise of digital technology has given birth to the concept of the virtual organisation, where the traditional physical office is replaced by a network of geographically dispersed teams connected through digital communication tools. Virtual organisations are highly flexible, with fluid structures that allow for rapid reconfiguration in response to market changes (Davidow & Malone, 1992).

This structure is particularly advantageous for global companies, enabling them to tap into talent across different regions and operate 24/7. However, it also presents challenges in terms of maintaining organisational culture, ensuring effective communication, and managing performance across dispersed teams.

3.2 Flexible, Fluid Structures

Modern organisations, especially those in fast-moving industries, are increasingly adopting flexible and fluid structures. These structures are less hierarchical and more adaptable, allowing for quick decision-making and innovation. They often rely on cross-functional teams that come together for specific projects and dissolve once the project is completed (Burns & Stalker, 1961).

Flexible structures are ideal for organisations that need to respond rapidly to technological advancements and market demands. However, they can also lead to ambiguity in roles and responsibilities, making it challenging to maintain accountability and consistency.

4.0 Organisational Structures in Global Contexts

4.1 Transnational, International, and Global Organisations

As organisations expand globally, they face increased complexity in managing operations across different countries and cultures. Transnational organisations, for instance, seek to balance global efficiency with local responsiveness by integrating operations across multiple regions while allowing for local adaptation (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989).

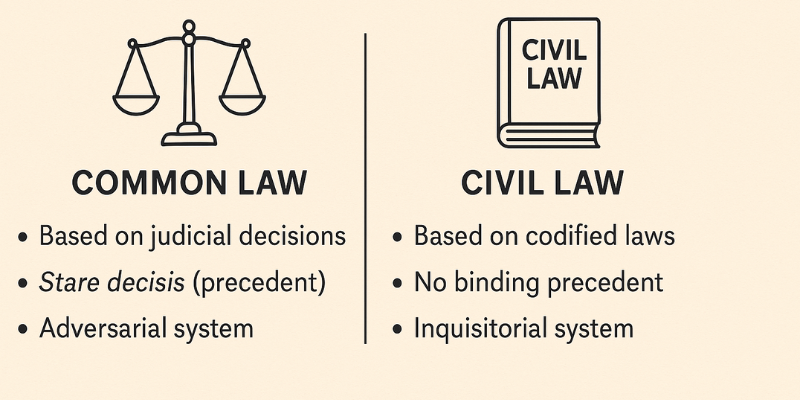

International organisations may adopt a centralised structure where key decisions are made at the headquarters, while global organisations may decentralise decision-making to cater to local market needs. These structures must be designed to navigate the challenges of cultural diversity, legal requirements, and varying market conditions.

Organisational structure is not a one-size-fits-all concept. The choice of structure depends on various factors, including the size and scope of the organisation, the industry in which it operates, and its strategic objectives. From traditional bureaucratic models to modern, flexible, and virtual structures, each has its advantages and challenges. As organisations continue to globalise, they must adopt structures that not only support their current needs but also provide the flexibility to adapt to future challenges.

References:

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (1989) Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution. Harvard Business School Press.

Burns, T., & Stalker, G. M. (1961) The Management of Innovation. Tavistock Publications.

Davis, S. M., & Lawrence, P. R. (1977) Matrix. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Davidow, W. H., & Malone, M. S. (1992) The Virtual Corporation. HarperCollins Publishers.

Heckscher, C. (1994) Defining the Post-Bureaucratic Type. In Heckscher, C. & Donnellon, A. (Eds.), The Post-Bureaucratic Organization: New Perspectives on Organizational Change. Sage Publications.

Mintzberg, H. (1979) The Structuring of Organizations: A Synthesis of the Research. Prentice-Hall.

Prahalad, C. K., & Doz, Y. L. (1987) The Multinational Mission: Balancing Local Demands and Global Vision. Free Press.

Weber, M. (1947) The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. Free Press.