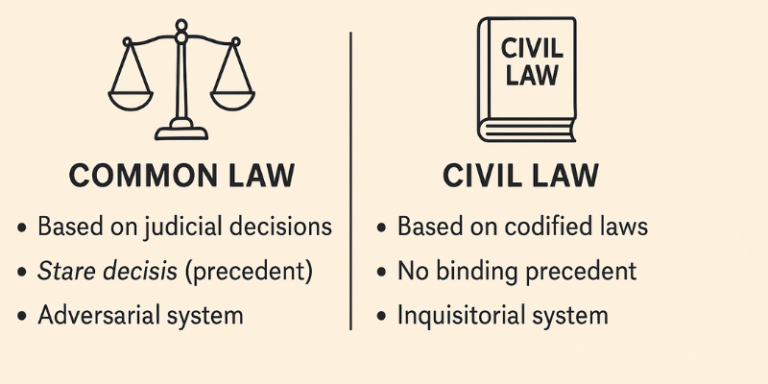

Legal systems around the world can be broadly divided into two major traditions: common law and civil law. These systems have profoundly shaped legal institutions, procedures, and doctrines across the globe. The distinction between them is rooted in historical, philosophical, and procedural foundations that continue to influence jurisdictions differently. This article explores the origins, principles, structure, and contemporary applications of both legal traditions, highlighting their similarities, differences, and global significance.

Origins and Historical Development

The common law system originated in England after the Norman Conquest of 1066 and was gradually consolidated through royal courts. It is characterised by the doctrine of stare decisis—the principle that decisions by higher courts bind lower courts, ensuring consistency and predictability (Slapper & Kelly, 2016). Common law expanded through British colonialism, becoming the basis for legal systems in countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and India.

In contrast, the civil law tradition traces its roots to Roman law, particularly the Corpus Juris Civilis of Emperor Justinian in the sixth century. Civil law was further codified during the Enlightenment, most notably with the Napoleonic Code of 1804. The system spread across continental Europe and was exported through colonisation to Latin America, Africa, and parts of Asia (Zweigert & Kötz, 1998).

Core Characteristics

One of the fundamental distinctions lies in sources of law. In common law systems, judicial decisions are primary sources of law alongside statutes. Judges play a creative role in shaping law through case precedents (Elliott & Quinn, 2021). In contrast, civil law systems place codified statutes at the forefront, and judicial decisions have interpretative but not binding authority (Bell et al., 2014).

Legal reasoning also differs. Common law reasoning is inductive: it builds rules from particular cases. Civil law employs deductive reasoning, applying abstract codes to specific disputes (Glendon, Gordon & Osakwe, 1999). Consequently, civil law judges act more as investigators, whereas common law judges serve as neutral arbiters between parties.

In terms of procedural structure, civil law litigation tends to be inquisitorial, meaning the judge plays an active role in gathering and examining evidence. Common law litigation is adversarial, with parties largely controlling the presentation of evidence and argumentation (Merryman & Pérez-Perdomo, 2007).

Judicial Roles and Court Systems

In civil law jurisdictions, judges are career professionals, often entering the judiciary after university and specialised training. Their primary responsibility is to apply the law as written. Conversely, common law judges often emerge from legal practice, typically after serving as barristers or solicitors. The adversarial system in common law grants judges discretion to interpret statutes and precedents, sometimes even developing new legal principles (Hutchinson, 2012).

Court hierarchy further demonstrates divergence. Common law jurisdictions typically feature layered court systems with appellate and supreme courts capable of making binding precedents. Civil law systems also have hierarchical courts, but precedents set by higher courts are persuasive rather than binding, focusing more on uniform statutory interpretation (Van Caenegem, 2002).

Codification and Legislation

Codification plays a pivotal role in the civil law system. Codes such as the Civil Code, Penal Code, and Commercial Code provide exhaustive legal frameworks. For instance, France’s Code Civil outlines rights and obligations in private law, aiming for clarity and completeness (Bell et al., 2014).

Common law countries use statutes extensively but do not typically codify the entirety of legal fields. Instead, statutory law complements the judge-made common law. For example, contract and tort law in the UK remains largely uncodified, governed by a mix of precedents and legislation (Poole, 2016).

Influence and Hybrid Systems

Globalisation and legal pluralism have led to hybrid legal systems, especially in former colonies and international contexts. For instance, South Africa and Louisiana (USA) incorporate both common and civil law elements. Similarly, international tribunals like the International Court of Justice use a mix of legal traditions in their rulings (Glendon, Gordon & Osakwe, 1999).

The European Union legal system also blends features of both traditions. The European Court of Justice operates under civil law principles but increasingly cites its own previous decisions, reflecting common law influences (Arnull, 2006).

Advantages and Criticisms

Civil law systems are often praised for clarity and predictability, thanks to comprehensive codes. However, critics argue that rigid adherence to codes can hinder adaptability and ignore the nuances of real-life cases (Zweigert & Kötz, 1998).

Common law’s flexibility and responsiveness to new circumstances are considered strengths. Yet, the system may suffer from complexity, unpredictability, and high litigation costs due to reliance on case law and legal representation (Slapper & Kelly, 2016).

Recent Developments and Convergence

There is a noticeable convergence between the two traditions in the 21st century. Civil law systems increasingly allow for precedent to guide decisions, and common law jurisdictions like the UK and Australia are codifying aspects of their legal systems (Nelken, 2001).

Additionally, international commercial arbitration and transnational law demand cross-system compatibility. Legal education is also becoming more comparative, enabling practitioners to navigate both systems effectively (Mattei, 1997).

Understanding the common law and civil law traditions is essential to appreciating the diversity and functionality of legal systems worldwide. While rooted in different philosophies and procedures, both traditions aim to deliver justice and uphold the rule of law. The evolving legal landscape, influenced by globalisation and legal innovation, continues to blur the lines between them. Ultimately, both systems contribute significantly to the development of modern jurisprudence and global legal order.

References

Arnull, A. (2006) The European Union and its Court of Justice. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bell, J., Boyron, S. and Whittaker, S. (2014) Principles of French Law. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elliott, C. and Quinn, F. (2021) English Legal System. 21st edn. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Glendon, M.A., Gordon, M.W. and Osakwe, C. (1999) Comparative Legal Traditions: Text, Materials and Cases on Western Law. 2nd edn. St. Paul: West Publishing.

Hutchinson, A.C. (2012) Is Eating People Wrong? Great Legal Cases and How They Shaped the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mattei, U. (1997) Comparative Law and Economics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Merryman, J.H. and Pérez-Perdomo, R. (2007) The Civil Law Tradition: An Introduction to the Legal Systems of Europe and Latin America. 3rd edn. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Nelken, D. (2001) ‘Comparing legal cultures’, in Reimann, M. and Zimmermann, R. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 561–581.

Poole, J. (2016) Textbook on Contract Law. 13th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Slapper, G. and Kelly, D. (2016) The English Legal System. 18th edn. London: Routledge.

Van Caenegem, R.C. (2002) European Law in the Past and the Future: Unity and Diversity over Two Millennia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zweigert, K. and Kötz, H. (1998) An Introduction to Comparative Law. 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.