The pursuit of a meaningful and fulfilling life is a universal human aspiration, yet few philosophies encapsulate this goal as elegantly as the Japanese concept of ikigai. Rooted in centuries of tradition and culturally embedded in Japanese society, ikigai offers a compelling framework for longevity, happiness, and purpose. This article explores the origins, principles, and benefits of ikigai, drawing upon academic literature, psychological research, and cultural analyses.

1.0 Defining Ikigai

The term ikigai (生き甲斐) can be translated as “reason for being” or “a reason to wake up in the morning” (Garcia and Miralles, 2017). It is composed of two Japanese words: iki (to live) and gai (worth). Unlike Western concepts that may separate happiness from life’s purpose, ikigai blends daily satisfaction with a long-term sense of meaning. According to Mathews (1996), ikigai does not necessitate grand achievements or material success, but often lies in the everyday — relationships, routines, and personal passions.

2.0 Historical and Cultural Context

The concept of ikigai has been embedded in Japanese culture since the Heian period (794–1185), where it was associated with both aesthetic beauty and moral worth (Kumano, 2018). It gained broader popularity during the post-war era as Japan experienced significant economic growth and societal change. Despite modernisation, the importance of ikigai remains resilient in contemporary Japanese society. It is particularly relevant in regions like Okinawa, home to one of the world’s highest concentrations of centenarians (Buettner, 2008).

Okinawans attribute their long lives to several factors: a healthy diet, strong community bonds, daily activity, and above all, having a sense of ikigai (Buettner, 2017). Elders in Okinawa rarely retire in the conventional sense. Instead, they continue to engage in purposeful activities — whether gardening, teaching, or helping grandchildren — well into their 90s.

3.0 The Ikigai Framework

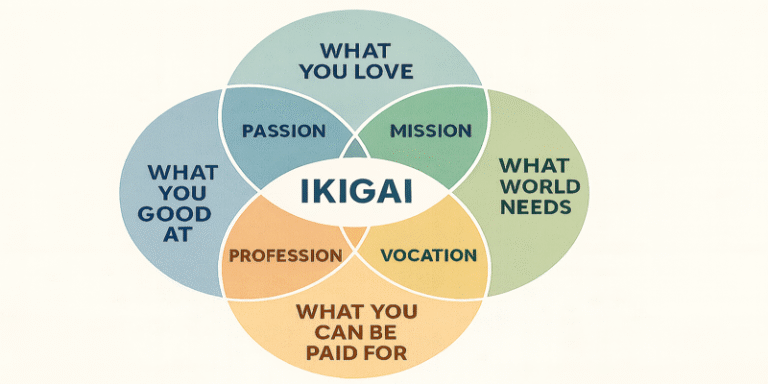

The modern interpretation of ikigai, popularised in Western literature, is often depicted as a Venn diagram comprising four intersecting circles: what you love, what you are good at, what the world needs, and what you can be paid for (Garcia and Miralles, 2017). The centre — where all four domains overlap — is your ikigai. While this framework has gained popularity for its clarity and adaptability, some scholars argue it oversimplifies the traditional Japanese understanding (Ikeda, 2021).

Nevertheless, the diagram serves as a practical tool for self-reflection. It encourages individuals to align personal passions with professional pursuits, while considering broader social contributions. This alignment is closely linked to the psychological concept of eudaimonia — a deep, meaningful happiness, as opposed to fleeting pleasure (hedonia) (Ryan and Deci, 2001).

4.0 Ikigai and Psychological Wellbeing

Psychological research supports the association between ikigai and mental health. A large-scale Japanese study by Sone et al. (2008) involving over 43,000 participants found that individuals with a clearly defined ikigai had significantly lower risks of cardiovascular disease and mortality. Furthermore, having ikigai was correlated with lower levels of psychological distress, even after controlling for socioeconomic and demographic variables.

Similarly, research by Imai et al. (2012) identified ikigai as a predictor of both subjective wellbeing and resilience among older adults. These findings resonate with Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000), which posits that autonomy, competence, and relatedness are key psychological needs. Ikigai, by encompassing these dimensions, acts as a psychological anchor.

Moreover, a study by Mori et al. (2017) found that even among patients with terminal illness, those who reported a continued sense of ikigai demonstrated better emotional adjustment and reduced existential distress. This highlights its therapeutic potential across the lifespan.

5.0 Ikigai in the Workplace

In the professional sphere, the application of ikigai principles can improve job satisfaction and employee engagement. According to a study by Yagi and Sano (2020), Japanese workers who identified their work as part of their ikigai were more likely to report job fulfilment and organisational commitment. In contrast, those who lacked purpose in their roles reported higher burnout and absenteeism.

Western businesses are beginning to incorporate ikigai into corporate well-being programmes, leadership development, and coaching models (Robinson, 2021). These adaptations, while beneficial, must be approached carefully to avoid commodifying a deeply cultural construct.

6.0 Critiques and Considerations

While ikigai offers a compelling lens for understanding life satisfaction, it is not without critiques. Some scholars caution against its misappropriation in Western self-help culture, where it is often decontextualised from its cultural roots (Ikeda, 2021). There is also a risk of individualising responsibility for happiness, ignoring systemic and societal factors that constrain people’s ability to pursue purpose.

Furthermore, the pressure to “find one’s ikigai” can become burdensome. As Kumano (2018) notes, not everyone has a clearly defined passion or calling, and for many, ikigai may evolve over time. Thus, flexibility and compassion are key to applying this philosophy meaningfully.

Ikigai is more than a lifestyle trend or productivity tool; it is a holistic approach to living with intention, deeply rooted in Japanese culture and validated by psychological research. By integrating passion, skill, contribution, and sustainability, it provides a framework for achieving not just longevity, but quality of life. However, its implementation must be culturally sensitive and personally adaptable, acknowledging the diversity of human experiences.

Whether found in a career, family, hobby, or community, ikigai encourages a life of purpose — not just for personal fulfilment, but for the benefit of others and the world at large.

References

Buettner, D. (2008) The Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer from the People Who’ve Lived the Longest. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic.

Buettner, D. (2017) The Blue Zones of Happiness: Lessons From the World’s Happiest People. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic.

Deci, E.L. and Ryan, R.M. (2000) ‘The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior’, Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), pp. 227–268.

Garcia, H. and Miralles, F. (2017) Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life. London: Hutchinson.

Ikeda, Y. (2021) ‘The Cultural Misuse of Ikigai in Western Psychology’, Journal of Japanese Studies, 47(1), pp. 89–112.

Imai, T. et al. (2012) ‘The Association of Ikigai with Health and Wellbeing among Japanese Elders’, Aging and Mental Health, 16(5), pp. 554–559.

Kumano, M. (2018) ‘On the Concept of Ikigai: A Psychosocial Perspective’, The Japanese Psychological Research, 60(4), pp. 207–219.

Mathews, G. (1996) What Makes Life Worth Living? How Japanese and Americans Make Sense of Their Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mori, A. et al. (2017) ‘Ikigai and End-of-Life Care: Insights from Terminal Cancer Patients’, Palliative and Supportive Care, 15(4), pp. 415–421.

Robinson, L. (2021) ‘How Companies are Embracing Ikigai for Employee Wellbeing’, Harvard Business Review, [Online] Available at: https://hbr.org (Accessed: 1 July 2025).

Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L. (2001) ‘On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-being’, Annual Review of Psychology, 52, pp. 141–166.

Sone, T. et al. (2008) ‘Sense of Life Worth Living and Mortality in Japan: The Ohsaki Study’, Psychosomatic Medicine, 70(6), pp. 709–715.

Yagi, H. and Sano, K. (2020) ‘Ikigai and Work Engagement in Japanese Organisations’, Asian Business & Management, 19(3), pp. 311–329.