1.0 What is Blood Pressure and How is it Measured?

Blood pressure (BP) is the force exerted by circulating blood upon the walls of the arteries. It is an essential indicator of cardiovascular health and is measured in millimetres of mercury (mmHg). Two values are recorded: systolic pressure (pressure when the heart beats) and diastolic pressure (pressure when the heart rests between beats) (Porth, 2011).

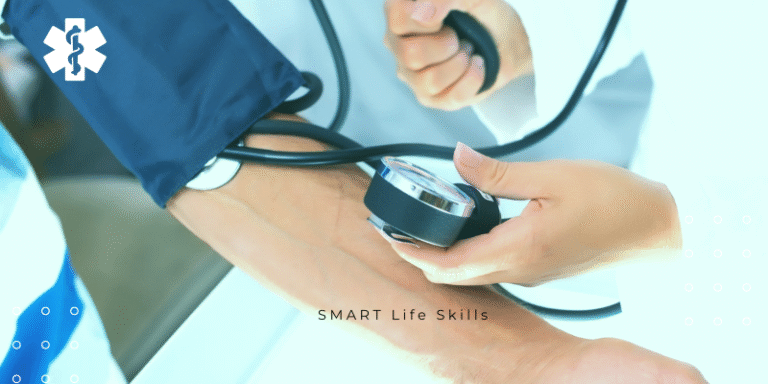

BP is typically measured using a sphygmomanometer, either manually with a stethoscope or digitally. The cuff is placed around the upper arm and inflated to constrict blood flow. As air is released, the practitioner listens for the Korotkoff sounds – the first sound indicates systolic pressure, and the point at which sounds disappear marks the diastolic pressure (Bickley & Szilagyi, 2017).

Modern automatic monitors use oscillometric methods to detect fluctuations in arterial wall pressure, providing systolic and diastolic readings, and often pulse rate (Pickering et al., 2005). Proper measurement requires the patient to be relaxed, seated, and supported, with the arm at heart level and no recent physical activity or caffeine intake (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2019).

2.0 Normal vs. High or Low Blood Pressure

The American Heart Association (AHA) and NICE categorize BP as follows (Whelton et al., 2018; NICE, 2019):

Normal: Systolic <120 mmHg and Diastolic <80 mmHg

Elevated: Systolic 120–129 mmHg and Diastolic <80 mmHg

Hypertension Stage 1: Systolic 130–139 mmHg or Diastolic 80–89 mmHg

Hypertension Stage 2: Systolic ≥140 mmHg or Diastolic ≥90 mmHg

Hypertensive Crisis: Systolic >180 mmHg and/or Diastolic >120 mmHg

Hypotension: Systolic <90 mmHg or Diastolic <60 mmHg

High blood pressure (hypertension) increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, kidney damage, and vision loss. It is often asymptomatic, earning the name “silent killer” (Carretero & Oparil, 2000). In contrast, low blood pressure (hypotension), while less common, can cause dizziness, fatigue, and fainting. In some individuals, particularly young adults or athletes, it may be normal if asymptomatic (Mayo Clinic, 2023).

3.0 How to Manage or Improve Blood Pressure

Lifestyle modifications are the first line of intervention for managing both elevated and high BP. The following strategies are widely supported:

Weight management: A reduction of even 5–10% of body weight can significantly lower BP (Appel et al., 2003).

Regular exercise: Aerobic activities such as walking, swimming, and cycling for at least 150 minutes per week help lower systolic BP by an average of 5–8 mmHg (Pescatello et al., 2015).

Dietary changes: The DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, and reduced saturated fat. It has shown BP reductions of up to 11 mmHg (Sacks et al., 2001).

Salt restriction: Reducing sodium intake to <2,300 mg/day (ideally 1,500 mg) significantly lowers BP (He & MacGregor, 2009).

Limiting alcohol: No more than two drinks per day for men and one for women (AHA, 2024).

Smoking cessation: Smoking damages blood vessels and raises BP. Quitting improves cardiovascular outcomes (Benowitz, 2010).

Stress management: Techniques such as mindfulness, deep breathing, and cognitive behavioural therapy can aid BP control (Chobanian et al., 2003).

4.0 Medications and Lifestyle Tips

When lifestyle changes are insufficient, pharmacological treatment becomes necessary. Common antihypertensive medications include:

Diuretics (e.g., thiazides): Promote sodium and water excretion, reducing blood volume.

ACE inhibitors (e.g., enalapril): Block the renin-angiotensin system to lower vascular resistance.

Calcium channel blockers (e.g., amlodipine): Relax blood vessels by inhibiting calcium flow into muscle cells.

Beta-blockers (e.g., metoprolol): Reduce heart rate and output, lowering BP.

The choice of drug depends on patient factors such as age, ethnicity, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes), and tolerance to side effects (Whelton et al., 2018; NICE, 2019).

Even when on medication, continuing healthy lifestyle habits enhances treatment effectiveness and may reduce the required dosage.

5.0 Reading a Blood Pressure Monitor and Understanding Results

Blood pressure monitors typically display:

Systolic pressure (top number)

Diastolic pressure (bottom number)

Pulse rate (optional)

For example, a reading of 135/85 mmHg indicates:

Systolic: 135 mmHg (borderline high)

Diastolic: 85 mmHg (high-normal)

May be considered Stage 1 hypertension, especially if consistent across readings.

Home monitoring is encouraged, especially for individuals with “white coat hypertension” (elevated readings in clinical settings only). To ensure accuracy:

Take readings at the same time daily

Sit calmly for 5 minutes before measurement

Record multiple readings and average them (Stergiou et al., 2018)

Understanding these numbers helps individuals monitor trends, adjust lifestyle habits, and seek timely medical intervention.

Blood pressure is a vital sign that reflects cardiovascular health and demands careful attention. With accurate measurement, awareness of normal and abnormal ranges, and appropriate lifestyle or medical interventions, individuals can significantly reduce the risk of serious conditions like heart disease and stroke. Understanding how to interpret BP readings empowers patients to take proactive control of their health.

References

American Heart Association (2024) What is High Blood Pressure? Available at: https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure (Accessed: 21 May 2025).

Appel, L.J., Moore, T.J., Obarzanek, E., et al. (2003) ‘A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure’, New England Journal of Medicine, 336(16), pp. 1117–1124.

Benowitz, N.L. (2010) ‘Nicotine addiction’, New England Journal of Medicine, 362(24), pp. 2295–2303.

Bickley, L.S. and Szilagyi, P.G. (2017) Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 12th edn. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

Carretero, O.A. and Oparil, S. (2000) ‘Essential hypertension: Part I: definition and etiology’, Circulation, 101(3), pp. 329–335.

Chobanian, A.V. et al. (2003) ‘Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure’, Hypertension, 42(6), pp. 1206–1252.

He, F.J. and MacGregor, G.A. (2009) ‘A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes’, Journal of Human Hypertension, 23(6), pp. 363–384.

Mayo Clinic (2023) Low blood pressure (hypotension). Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/low-blood-pressure (Accessed: 21 May 2025).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2019) Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management (NG136). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136 (Accessed: 21 May 2025).

Pescatello, L.S., MacDonald, H.V., Lamberti, L. and Johnson, B.T. (2015) ‘Exercise for hypertension: a prescription update integrating existing recommendations with emerging research’, Current Hypertension Reports, 17(11), pp. 87.

Pickering, T.G., Hall, J.E., Appel, L.J., et al. (2005) ‘Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans’, Hypertension, 45(1), pp. 142–161.

Porth, C.M. (2011) Essentials of Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Sacks, F.M., Svetkey, L.P., Vollmer, W.M., et al. (2001) ‘Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet’, New England Journal of Medicine, 344(1), pp. 3–10.

Stergiou, G.S., Palatini, P., Parati, G., et al. (2018) ‘European Society of Hypertension guidelines for blood pressure monitoring at home’, Journal of Hypertension, 36(9), pp. 1723–1738.

Whelton, P.K., Carey, R.M., Aronow, W.S., et al. (2018) ‘2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults’, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 71(19), pp. e127–e248.